On the snowy slopes of Mt. St. Helens, a ragged strip of crime-scene tape dangles from the branch of a roadside sapling. Flapping in the winter breeze, breaking the solemn wilderness silence, the bright-yellow plastic is a shocking speck of neon among the emerald expanse of firs.

Somewhere ahead, an overgrown trail winds through the woods to a creek, just downstream from a picturesque waterfall secluded by steep terrain and thick brush. This path, through a minuscule sliver of the vast Gifford Pinchot National Forest, is also dotted with strips of tape—this time red, marking spots where human bones were found on October 9.

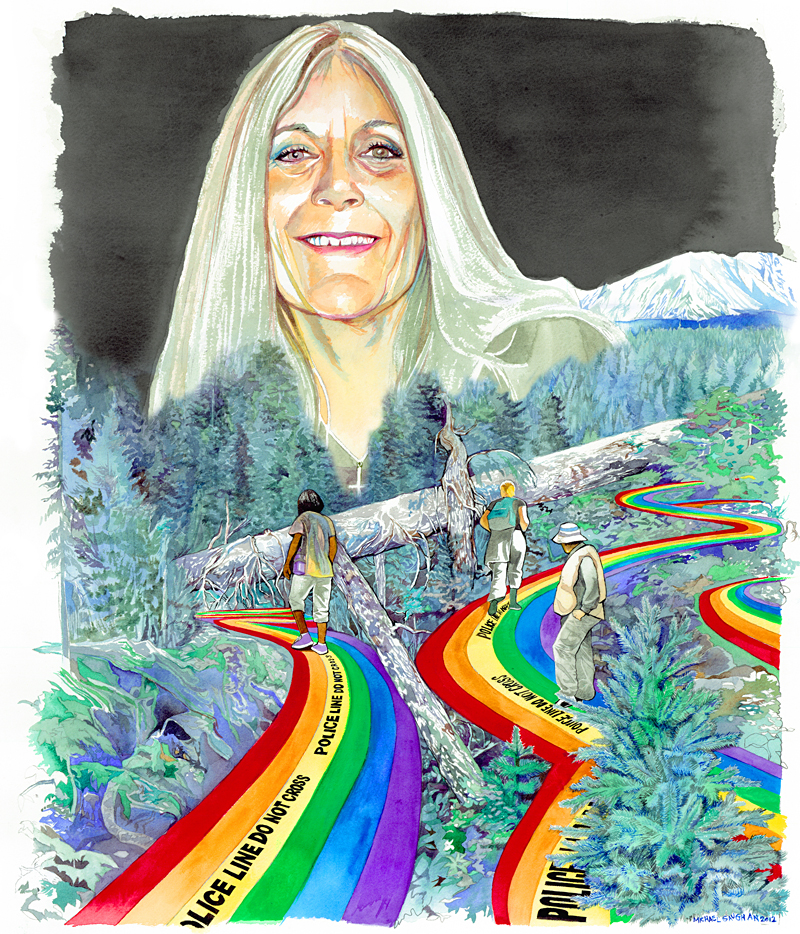

“A few miles up the road is the remains of a dead body,” says Emily McCarty, trudging through the ankle-deep snow. She and dozens of others scoured this neck of the woods throughout last summer and fall, but even cadaver-sniffing police dogs were ultimately unable to locate all that is left in this world of Marie Hanson.

Some of Hanson’s skeleton was collected into evidence. The rest, presumably, is still scattered across this backcountry hillside.

A 54-year-old grandmother, Hanson vanished while camping at the Rainbow Family Gathering, a legendary counterculture event that draws tens of thousands of hippies, freaks, and free spirits to a different national forest every Independence Day. McCarty, a Rainbow Family advocate, worked on behalf of Hanson’s family, cajoling the local police to pursue the case. She also tried to publicize the incident by posting on Examiner.com, a community news site. Her efforts, she says, were met mostly with indifference from both the cops and media.

Tears of frustration well up in McCarty’s eyes as she lights a cigarette with an unsteady hand. “She was out here for three fucking months,” she stammers. “It was hard to convince anybody she really was out here. When they finally found her, there was just this look of shock on the deputy’s face.”

Given the condition of Hanson’s remains, the county medical examiner had to verify her identity using dental records. But a silver bracelet found on the trail nearby was confirmation enough for those who’d known her. The jewelry was engraved with a Bible verse, Matthew 4:19: “And he saith unto them, Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

The Scripture is eerily fitting. While Rainbow festivities are debauched at times, the Gathering culminates with a group prayer for world peace. An easygoing but devout Christian, Hanson left her home in South Lake Tahoe, Calif., to proselytize the tie-dyed masses assembled in this remote corner of southwest Washington. An investigation is still ongoing, but the cause of Hanson’s death remains a mystery.

“It’s a suspicious death,” says Jeff Roberson, the detective handling the case for South Lake Tahoe Police. “Until we have something that indicates otherwise, it’s not a homicide.”

That Hanson went missing during her Rainbow expedition is not unusual. The Rainbow Family of Living Light, as it is formally known, is a magnet for disaffected young adults seeking to turn on, tune in, and drop out as if the Summer of Love had never ended. The so-called “Rainbow Trail,” a series of festivals and small regional gatherings, offers an alluring combination of positive vibes, free meals, and an off-the-grid lifestyle that make it easy to lose touch with the outside world.

But where others have turned up alive and well, Hanson’s life ended tragically. Now two law-enforcement agencies, her surviving family, and some of the most dedicated Rainbows are left wondering whether her demise was the result of an accident or something more sinister.

The foundation for the modern Rainbow Family was laid in the fall of 1969 when a group of hippies and Vietnam vets who had been camping near Big Sur packed their belongings and headed north. They ended up at a commune in Marblemount, Wash., a tiny hamlet just outside the boundary of North Cascades National Park in a bucolic river valley that the bohemian California transplants dubbed “The Magic Skagit.”

The group soon became known as “The Outlaws of Marblemount” for their willingness to guide draft dodgers and deserters across the Canadian border. According to Barry “Plunker” Adams, 66, a Navy veteran and one of the original Marblemount denizens, the Outlaws recruited additional members at the Oregon Country Fair, and the following year helped organize Vortex, a weeklong concert and counterculture event in Portland.

“We rolled out [of Vortex] flying the rainbow colors,” Adams recalls over the phone from his home in Montana. “Along the way I ran into other dreamers and visionaries, and we had a collective visionary process that took place. We fell into following a dream, a vision, and that became what’s known as the first Gathering.”

That inaugural Rainbow Family Gathering took place near Strawberry Lake, Colo., in the summer of 1972. Promoted by word-of-mouth and bolstered by a clever publicity stunt—the Rainbows sent an invitation to every congressman and United Nations delegate—the event drew an estimated 20,000 people, despite the threat of a police crackdown.

Equal parts beatnik and good ol’ boy, Adams says the secret to spontaneously establishing a city in the middle of nowhere is to provide adequate supplies and sanitation. He talks of enlisting Vietnam vets to chop firewood, purify water, and dig trench latrines. “You know that old saying,” he says with a laugh. “If you dig a shitter, they will come.”

The Gathering’s mantra then was “Welcome Home,” in honor of the troops returning from war, and the experience culminated with everyone joining hands in a silent prayer for peace. But while the war ended in 1975, and with it the hippie zeitgeist, the Rainbow Family, their Gatherings, and their mantra have managed to evolve and persevere. Attendance at this year’s event, held in the Skookum Meadow area of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, reportedly exceeded that of the original.

The allure, frequent Gatherers say, is a utopian atmosphere that emphasizes both individual freedom and collective action. There are no rules, no leaders, and no organization, at least not in the traditional sense. A council open to every attendee, regardless of age or experience, makes logistical decisions only after a consensus is reached. Volunteers operate dozens of makeshift kitchens that serve food free of charge, and, much as at Burning Man, cash transactions are strongly discouraged.

“It’s a return to community,” says a Rainbow from Seattle who goes by the nickname Circus Maximus. “It may be weird counterculture, but there’s something there that we’re missing in our e-mail and text-message lifestyle.”

The Rainbow adherence to loving thy neighbor and other tenets of Christianity is no coincidence. Spirituality plays a pivotal role in the culture, which combines environmentalism, socialism, and Native American customs with Judaism, Buddhism, paganism, and other faiths to form an eclectic, inclusive belief system. Mainstream society is derisively referred to as “Babylon.”

Michael Niman, an American Studies professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, spent 13 years researching the Rainbows for the doctoral thesis that became his 1997 book People of the Rainbow: A Nomadic Utopia. He says the Rainbow ideology and experience is often cathartic. “For many people I’ve spoken to, the time of the Gathering is a transformative experience,” Niman says. “You can slander it and call it a cult if you haven’t been there and haven’t researched it. It’s not something you’ll easily experience someplace else. It’s a profound sense of community.”

Of course, the Gathering also doubles as an excuse to throw a wild party in the woods. Although booze is only imbibed in “A Camp” (a motley assemblage of vagabonds and roughnecks, where chaos reigns supreme), pot smoke, public nudity, and drum circles abound. In Adams’ words, “It’s hippie Disneyland.”

Marie Hanson went to the Rainbow Gathering on a whim. She had just returned from an extended trip to New York to attend her son’s wedding, and she was, according to her family, reluctant to leave the creature comforts of home again so soon. But she’d heard talk of the peace rally with a prayer circle, and thought it sounded like a crowd that might like to hear a thing or two about Jesus.

“It was just a spur-of-the-moment thing,” says Billy Hanson, Marie’s husband of 35 years and former high-school sweetheart. “Our neighbor was going. He mentioned it to her, she mentioned to me, and she was off.”

Hanson had known her neighbors— 44-year-old Alan Peck, who goes by the nickname “Mellow,” and his girlfriend Cathy Ward, believed to be in her mid-50s—for less than two years, but they had a congenial relationship. Hanson was like that, says Nancy Enterline, the mother-in-law of Hanson’s daughter Tawny and the spokeswoman for the Hanson family. “Marie was a really, really friendly lady,” Enterline says. “She could make friends with anybody—somebody standing behind her in line at the grocery store—anybody. She’d go next door to hang out and watch videos or things like that.”

Hanson worked for the El Dorado County District Attorney’s Office for more than a decade before botched back surgery forced her into early retirement. Her main hobby was doting on her grandchildren, relatives say, and every weekend she managed the Sunday-school nursery at Sierra Community Church in South Lake Tahoe.

Hanson was also “an old hippie at heart,” Enterline says, who relished the idea of going on an adventure with her friends. The only thing holding her back was, well, her back. “She was in a lot of pain,” Enterline explains. “The family was amazed that she took off with this guy, and was planning on sleeping in the car because of her back.”

Hanson was a Rainbow rookie, but her travel companion, Peck, had attended several Gatherings. He arranged a ride-share via an online message board, and on the morning of July 1 they hit the road, accompanied by Peck’s black-and-white-speckled dog Bandit. Their respective significant others remained at home—Billy Hanson’s back is worse than his wife’s, and Ward planned to meet up with Peck and Hanson after attending a friend’s funeral.

In a brief phone interview, Ward says Peck promised both her and Hanson the time of their lives. “When I first met him, all he could talk about is how he wanted me to go to the Rainbow Gathering,” she says. “Alan was talking about it, and [Hanson] said it sounded like a neat thing she’d like to experience.”

Hanson and Peck arrived at their destination to find rows of parked cars stretching for miles on the shoulders of the surrounding Forest Service roads. They unloaded their minimal gear, parted ways with their driver, and embarked on the long hike up the trail to the Gathering site. A Rainbow woman who calls herself Momma Kimmie says she greeted Hanson that first day and noticed right away that she was hurting. “I could tell she was in pain,” Kimmie says. “She was ashen, her face looked stressed, and just the way she moved, she looked haggard.”

Peck and Hanson initially camped near “main meadow,” the Gathering’s city center, near Lovin’ Ovens, a well-known kitchen where Peck volunteered. The weather was much colder than anyone had anticipated. Snowdrifts nearly two feet high were still on the ground in shaded areas, and though it was plenty warm in the afternoon, overnight temperatures dipped into the low 40s.

By all accounts, Hanson managed to have at least a few pleasant experiences. She wore a shirt with angel wings drawn on the back, and traded for a doll and other trinkets to take home to her grandchildren. Kimmie crossed paths with Hanson a few days after their initial encounter, and noticed that her condition had improved. “She looked radiant,” Kimmie says.

But at some point Hanson’s achy back began to act up again, and she became badly sunburned. She also contracted a nasty stomach virus. Peck reportedly tried to care for her as best he could, bringing food and water back to their tent, and he eventually requested the help of Rainbows with first-aid training.

“She didn’t need much care,” recalls Rob Savoye, who met briefly with Hanson and advised her to continue drinking fluids. “That flu had been going around. You basically shit and puked your brains out for 24 hours.”

Peck’s girlfriend Ward says she arrived late on the evening of July 5, driving a white Saturn sedan. She parked on the road, and began to inquire about how to find her friends. Someone remembered seeing the dog Bandit, and guided Ward to their campsite. She found Peck baking biscuits in one of the kitchens. Hanson, she was told, was in the tent convalescing.

With the Gathering rapidly winding down after the July 4 climax, the group moved their camp from the meadow to the road where Ward’s Saturn was parked. It was here that Hanson was reportedly last seen.

According to Enterline, Peck told police that Hanson had been missing for 72 hours, and the last time he saw her she was “stumbling down the street barefoot in shorts and a tank top, and heading toward the shitter.”

“He said he saw her and went back to sleep and never saw her again,” Enterline says. “He didn’t think it was a big deal. She went off somewhere, whatever.”

Hanson left behind all her possessions, including her wallet, purse, pain medication, and a doll she had gotten for her grand-children. Later that afternoon, Peck returned to the meadow area of the Gathering site to search for his missing neighbor. He showed several people her driver’s license, but all to no avail. On the evening of July 9, Peck phoned Billy Hanson.

“He said he’d lost my wife,” Hanson says ruefully. “It sounded like a bad joke.”

By the time the Skamania County Sheriff’s Office was notified of Marie Hanson’s disappearance, it had already dealt with more than two dozen other missing-person cases at the Rainbow Gathering. The temporary wilderness metropolis was nearly 200 times the size of the nearest town (Cougar, Wash., population 122), and at least 30 miles away from cell-phone reception. Consequently, friends easily lost track of each other and lots of panicked parents reported that their sons and daughters had failed to check in as scheduled.

Although the Gathering is ostensibly governed by anarchy, there are volunteers who coordinate emergency services. The Rainbows practice a concept called “Shanti Sena,” a Sanskrit term coined by Gandhi that translates to “Peace Army.” It means, essentially, that if trouble arises, it is everyone’s duty to come to the rescue. Some people—Adams, Savoye, and Circus Maximus among them—take this calling quite seriously. They carry walkie-talkies, extinguish unsafe campfires, and doggedly pursue legit missing-person reports.

“We operate on a case-by-case basis,” says Adams, unofficially the Rainbow’s chief detective. “We’re tenacious. We don’t leave anyone behind. Once we start a search, we don’t end the search until we know for certain what has happened with whatever individual.”

But Adams and many of the most hard-core Shanti Sena devotees were already headed home when the alarm for Hanson was raised. Further complicating matters was the conflicting information received by police and the Hanson family. “We were contacted by every cuckoo bird on the planet,” Enterline says. “We didn’t know who to trust and who not to. Some people were crazy.”

Some reported seeing Hanson hitch a ride out of the Gathering in the back of a pickup. Still others said she’d been hanging out with a character nicknamed Owl. One person even went so far as to give a description to a police sketch artist. The resulting suspect—an older man with an Indiana Jones–style hat, braided hair, a beard, and thick glasses—bore a suspicious resemblance to Barry “Plunker” Adams.

Even though police later debunked these rumors (the would-be witness later admitted he’d never actually seen Hanson during the Gathering) the false leads initially forced Hanson’s family to consider the possibility that she might have been kidnapped, and investigators to suspect Hanson had hit the fabled Rainbow Trail.

Also known as “the hippie road,” the Trail is the modern-day equivalent of following the Grateful Dead on tour. Teenage dropouts and adventuresome 20-somethings scrape together enough cash to attend music festivals up and down the West Coast or hitchhike to various Rainbow Family potlucks in a happy-go-lucky odyssey that usually ends when the weather turns cold. Not always the most responsible young adults, they sometimes lose touch with their families, who then contact authorities fearing the worst.

In the summer of 2010, in a disappearance not unlike Hanson’s, a 20-year-old St. Louis woman named Melanie Harmann was partying with friends at Hempfest in Seattle when she seemingly vanished into thin air—like Hanson, she left behind her cell phone, journal, and wallet. The case generated headlines, and Harmann’s mother, Skyler Wiseman, received a tip that her daughter had been spotted boarding a bus headed east, perhaps to attend a Rainbow event. After being bounced back and forth between two police departments, Wiseman eventually took matters into her own hands and boarded a flight to Spokane.

Wiseman says she marched into the campground carrying a bag of oranges and two jugs of water which she hoped to trade for information, and describes the scene as part Jewish kibbutz, part Hobbit shire, and part Avatar “because about a third of the people were naked and painted blue.” When she eventually found Melanie, the latter was stunned by the news that she had been reported missing. Despite the ordeal, Wiseman says she can understand the appeal of the Rainbow. “I could see how Mel could get sucked into that,” she says. “I’m not saying it’s a cult at all—she was not held by force—but it is a very enticing lifestyle to not have to worry about where your next meal will come from.”

Naturally, not every tale from the Rainbow Trail has a happy ending. Enterline says that when the family created a “Marie Hanson Missing” Facebook account and website, she was bombarded by heart-wrenching messages from parents whose estranged kids are rumored to be drifting with the Rainbows.

Adams and other Rainbow elders acknowledge that runaways and other marginalized young people are drawn to their Gatherings. But they also point out that their group makes a convenient scapegoat. “It’s kind of reminiscent of when the Gypsies would roll through,” Adams says. “It’s the circus come to town. ‘The kids will run off, you have to watch ’em!’ “

Neither the FBI’s National Crime Information Center nor the Center for Missing and Exploited Children report investigating any missing-person cases involving the Rainbow Family. Todd Matthews, a spokesman for NamUs, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, says it’s not uncommon for individuals affiliated with groups such as the Rainbows to cut ties with their kin and never look back. “Some people are alive and well,” he says. “They’re out there. If you’ve been alienated from your family and [are] living an alternative lifestyle, if you Google yourself, you might find they’re looking for you.”

But Enterline was deeply disconcerted by how quick the authorities were to assume that Hanson would abandon her family and chase the Rainbow. “The police just kept telling us ‘People make stupid decisions. Adults make decisions to leave their normal lives all the time,’ ” she says. “When I talk to people who have missing family members now, I’m hearing law enforcement all over the U.S. are telling people this.”

Both law-enforcement agencies involved in the search for Hanson say they were always skeptical of the Rainbow Trail theory, considering her disability and strong family and community ties, and this far-fetched scenario had to be eliminated as a possibility. Once it was determined that Hanson was likely still somewhere in the vicinity of the Gathering, the real challenge became finding out where exactly she was—and, more important, how she got there.

On July 13, four days after Hanson was reported missing, Enterline and her daughter-in-law Tawny traveled from South Lake Tahoe to the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. By the time they arrived, most of the volunteer kitchens had stopped cooking and just a few hundred people remained.

The search effort for Hanson had been underway in earnest for only a very short while. In time, a dedicated group of Rainbows—including several people with formal search-and-rescue training—would look high and low in the woods where Hanson was last seen, using a grid system to methodically traverse the rough terrain. But most people left the Gathering with no idea that anything was amiss.

The sheriffs, meanwhile, were still busy sifting rumors about Hanson, Owl, and the Rainbow Trail. “One of our biggest problems was convincing law enforcement that the stories were just that: stories,” Adams grumbles. “That they should make moves to get back there and bring their dogs and find this woman.”

Skamania County Sheriff Dave Brown says the delayed deployment of search-and-rescue canines stemmed from concerns about parvo, a deadly disease spread by dog feces (Enterline: “That’s a stupid excuse”), and hypodermic needles at the Gathering site (the Rainbow cleanup crew reportedly did find one hypodermic needle, but only one). The dogs weren’t utilized until mid-August, more than a month later, and the initial search by sheriffs on July 14 focused on the main meadow area, much to the chagrin of the Rainbows.

The Rainbow Family takes great pains to leave no trace, and a sizable cleanup crew was already busy scouring the meadow and surrounding areas for cigarette butts and other bits of “microtrash.” If there was a corpse anywhere near the meadow, they argued, it would already have been found.

“The sheriffs didn’t consider any of the Rainbows a useful source of information,” Savoye says. “The pros came in and thought they knew what they’re doing. We all said searching the meadow is stupid. We all knew she had gone down the road to camp.”

The Rainbow Family’s relationship with law enforcement has always been adversarial. Because the Gatherings take place on public forest land, the primary agency that deals with them is the U.S. Forest Service, or USFS. In 2008, the American Civil Liberties Union issued a report stating that the federal agency was guilty of “harassment and general overzealous enforcement” in their dealings with the Rainbows.

The USFS public-affairs office did not respond to repeated requests for comment for this story, but 2011, the Rainbows say, was the first year that the feds largely left them to their own devices. And while the Rainbows were extremely pleased with the hands-off treatment, there is lingering suspicion that because of it the authorities dragged their feet in the search for Hanson. Brown, however, insists that the steps taken by his office in Hanson’s case were “consistent with how we’d treat any report that comes in on any given day.”

Controversy aside, the search-and-rescue dogs failed to find any scent of Hanson in the vicinity of the meadow. Likewise, the Rainbow cleanup crew completed their restoration project without uncovering the slightest trace of the missing grandmother.

Adams says he formed a special Shanti Sena task force—”Rainbow Team Marie”—to continue the search efforts. Savoye and Circus Maximus went so far as to rappel several hundred feet down the cliffs adjacent to the waterfall near where Hanson and Peck were last camped to investigate the possibility that she’d fallen in and been swept away.

Others worked diligently to get the word out online. As time wore on, Enterline says, the bogus police sketch and talk of Owl actually proved useful. Long after the case went cold, Web forums frequented by Rainbows were abuzz with talk of Owl. “It turns out there are five or 10 Owls,” Enterline says. “It reinvigorated the case and got people talking again.”

The key development, though, didn’t occur until mid-September. A young man who wished to remain anonymous contacted Enterline through a third party. He claimed that he had spent July 7, the entire day, with Hanson and Peck and camped with them that night near Ward’s Saturn. Enterline and the rest of the Hanson family were both shocked and suspicious. There hadn’t been any confirmed eyewitness sightings of Hanson after July 6, and Peck reported July 9 that she had been missing for 72 hours.

But the young man’s story sounded legit. He said that he’d wanted to visit South Lake Tahoe and had made plans to hitch a ride there with the natives. He also relayed details about Hanson that would have been impossible to fabricate. Hanson was quite sick, he said, “barely keeping food or water down.” The man said the last time he’d seen Hanson was around 1:30 a.m. on the morning of July 8.

Upon further questioning, Peck revised his story: He’d actually seen Hanson on the road stumbling toward the trench latrine at around 6:30 a.m. on July 8. “One of the reasons we think Mellow said ‘I haven’t seen her for 72 hours’ is he wanted police to think she’d been gone longer than she was,” Enterline says. “We have a culture that thinks they won’t look for an adult unless they’ve been gone for 72 hours.”

Roberson, the South Lake Tahoe detective, says it’s a common misconception that missing-person cases can’t be immediately reported (they can), and that Peck could legitimately have lost track of time. “I’ve never hemmed him up about whether he said 72 hours or whether he actually thought it was 72 hours,” Roberson says. “You’re up there, you’re high all the time, and you’re not really tracking the days—what day it is or what the date is.”

But the erroneous timeline wasn’t the only misinformation from Peck. “One time he’d say he was camped next to this kitchen, and the next time it was another,” Enterline says. “He said ‘We were parked by the gate,’ but he didn’t know which one, and there are three.”

Seeking to remove all doubt, the Hanson family paid for Peck to fly back to the Gathering site on September 29. Escorted by Skamania County Sheriff’s deputies, he pinpointed the spot where he and Hanson had camped last.

A previous search of the bushes near that area had turned up a bag of soiled clothes resembling those worn by Hanson during the Gathering. With winter fast approaching, the sheriffs and Rainbows combined forces and redoubled their efforts. On October 2, the cadaver-sniffing dogs picked up a scent; the following week they made the grisly discovery.

Much of the surrounding hillside where Hanson’s skeleton was found is brutally steep—topography maps put the drop at several hundred vertical feet over less than a quarter mile—but for all the countless hours spent searching, some of her bones were discovered in a patch of underbrush less than 15 yards away from her campsite, easily within shouting distance of the road.

“We were pretty appalled,” Enterline says. “I think it would be safe to say I’m horrified by how close it was to the road.”

Police say they are still awaiting the results of several tests on Hanson’s remains. In addition to a toxicology report, an anthropologist and pathologist will analyze the remains, looking for marks to confirm the theory that forest animals impacted the condition and location of her body.

“I don’t think in the end it will point us in any other direction other than what I would characterize as an unfortunate incident for Mrs. Hanson and her family,” Sheriff Brown says. “There isn’t any information we’ve been able to gather that indicates there’s any foul play involved.”

Nevertheless, several questions loom large about the way Peck and Ward handled Hanson’s disappearance. Why didn’t they speak up sooner and more forcefully? Why didn’t they search the woods near the car, if that’s where Peck saw Hanson headed on the morning of July 8? And if Hanson was in such poor physical condition, why didn’t they leave the Gathering and take her to the hospital?

Reached by phone last December 18, Peck is in no mood to discuss the matter. “That’s pretty fucked up to be bringing this shit up at Christmastime,” he says before abruptly ending the call. “It ain’t cool. Don’t call me at Christmastime and bring up somebody’s death. It’s not fucking cool.”

His girlfriend, Ward, talks briefly but offers little clarification. Improbably, she maintains that she never once laid eyes on Hanson from the time she arrived at the Gathering on July 5 to the time she and Peck left the forest, according to police, on July 10, “I never saw her,” she says repeatedly. “She got up in the middle of the night to go to the restroom and never came back.”

Ward says she got separated from Peck several times, and at one point he was left searching for both her and Hanson. And yet she says she still managed to have a good time. “I thought it was beautiful. It was a beautiful gathering, lots of music, good people, the food was free. Everybody was so happy and friendly and nice and warm. It was a great experience.”

The couple’s trip home was reportedly far less pleasant. First they lost the keys to the Saturn and had to summon a locksmith to the National Forest. Then, on July 11, the car broke down in Reno, about an hour and a half away from South Lake Tahoe. Finally, multiple sources say Ward ended up spending about three weeks in the psychiatric ward of Reno’s Renown Regional Medical Center.

“I was very upset,” Ward says when asked about her time at the hospital. “I was disturbed by the death of my friend, and the fact that we couldn’t find Marie. Yeah, I went to counseling. It was very stressful for me.”

Adding to the intrigue, Adams says that when he investigated Peck’s previous Rainbow Gathering participation, he learned that the man who calls himself Mellow “really liked being naked” at the events. According to Adams, Peck’s first Gathering was in Colorado in 1992, and he roamed the festival grounds in the nude carrying “a little funny sign” that advertised his availability to potential female companions.

Adams says some Rainbows recall Peck as being an airhead, but others found him deceptively sharp. “I was hearing from a number of people that this cat Mellow was not very bright, that he was spacey or all whacked-out,” Adams says. “In fact, what I learned was that he’s bright—very bright—and enjoyed getting it over on people . . . in discussions people found him to be extremely well-read, extremely intelligent, and maybe a tiny bit of a smartass.”

Barring new evidence or some unforeseen development, the exact cause of Hanson’s death will likely remain a mystery. Adams believes the most plausible version of events is that Hanson woke early in the morning, headed into the woods to relieve herself, and lost her bearings in the predawn darkness. “She could think she’s gone maybe five feet, but she gets turned around,” he says. “It’s deep boonies, pard.”

Not only Hanson lost her life at the Gathering in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Two other adults were found dead in their tents, both of natural causes. But three women also gave birth, and Adams notes that there is some symmetry there. “As Bob Dylan, the great prophet, said, ‘Those who aren’t busy being born are busy dying,’ ” Adams says. “Gatherings are that way. People live and people are born and life goes on.”

But for the Hanson family and many of the Rainbows who searched for her, there is cold comfort in such coincidences. Back on Mt. St. Helens, Emily McCarty kneels to light a candle as a makeshift memorial. She says that next year, after the snow has melted, she wants to help Hanson’s family return to the woods and recover the remains. In the meantime, McCarty says, the bizarre events surrounding Hanson’s disappearance and discovery are nearly impossible to put out of her mind.

“It creeps me out,” she says. “None of this has gone the way it should have. It’s not normal circumstances, not on any level.”