It’s my first night in Havana, and I’m seated in a paladar discussing a nativity scene. Across from me is Daniel Ryan Smith, a graphic designer and friend from Seattle who has been here before—this is his fifth trip to Havana. We just walked by the elegantly lopsided stone Catedral de San Cristobal, and there in front of us was the famous scene— a remnant of Christmas, which had just passed a week before. Smith tells me that he doesn’t remember seeing so many Christian artifacts on any of his prior trips to Cuba. Indeed, there are a lot of Christmas trees around, not to mention the Christmas garland looping around the portraits of Che found in bars and restaurants, and the countless Santas we’d already seen. Saint Nicholas is here in the house with us, alongside Cuba’s patron saint, Saint Lazarus.

We order fried fish and mojitos and study the oceanic taxidermy on the wall of this private, family-run restaurant: Marlin, shark, black flying fish with enormous wings, frowning mahi-mahi. A blind man with a guitar is seated at the door, still and silent, waiting for the right moment to strike the chord, to come alive and sing.

Asking for the bathroom, I’m directed through a door that leads into a family living room and kitchen. Two women sit on a gold, floral-patterned couch from the ’70s, watching a telenovela—one is changing a baby’s diaper. Our waiter sits at the table behind the couch eating dinner while a woman in a shower cap cooks in the kitchen, preparing the fish we just ordered. I’m suddenly a part of this family’s world, one that I didn’t know existed beyond that door.

Until recent times, the situation was reversed. A living room was what one saw from the street, and behind the closed door, a restaurant flourished, a kind of speakeasy. While all retail business was declared illegal after Fidel Castro took power in 1959, paladares, which operated for many years underground (along with all other private businesses), were legalized in the early ’90s. Now businesses are everywhere, out in the open, often in the front rooms of people’s homes—from nail parlors and barbers to cell-phone repair shops to, yes, even a sideshow shooting range offering to educate your child about the revolution. The “education” here consists of rustic BB guns and faded portraits of the leaders of the Cuban revolution: Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos. These three, shooters are told, organized the guerrilla war that toppled the reign of corrupt president Fulgencio Batista. Thusly educated, one can take aim at the soda cans and stuffed animals strung up against the back wall.

Each doorway is a frame, offering a different picture of life in Havana, lived in full view. Doors to homes are thrown open in the evenings to let in cooler air. Inside are crumbling marble staircases, laundry strewn across living rooms, interior design and furniture from past eras. All framed by the exquisitely collapsing, molding buildings of old Havana—bright paint peeling off in sheets like dead skin.

Smith first came to Havana in 2006 to make posters. As part of a graphic-design exchange called Sharing Dreams, organized by the American Institute of Graphic Arts, he traveled with other American graphic designers to Havana to meet Cuban designers and collaborate on a poster exhibition. While Sharing Dreams may have opened the door, Smith wasn’t totally satisfied with the project.

“The theme of the posters we were making was Love Conquers All—which came across as sentimental, very Hallmark,” Smith recalls. “I wanted to see what people were really doing, what they were really working on—not this made-up thing.”

Smith says he had preconceived ideas about Cuban graphic design, mostly because of the poster’s role in the propaganda efforts that followed the Cuban Revolution. “I pictured state-sponsored propaganda frozen in the 1960s or 1970s,” he says, “because that’s all I’d ever seen, the state-sponsored stuff. Cuban posters are world-famous, but it’s their communist propaganda—reproduced for decades—that is known outside the Island.”

Since cultural and commercial exchange between the U.S. and Cuba has been virtually non-existent since the revolution—the result of a strict embargo against the island nation—these classic propaganda posters alone formed the basis of Smith’s stereotypical view of Cuba. Heroic posters featuring the fiery yet languid gaze of the guerrilla leader Che and incessant calls to arms; hard-edged graphics printed in bold, flat colors; ink as dense as wall paint.

In the past, post-revolution Cuban posters embodied the voice of the state since the means, the production, and the distribution of posters were entirely controlled by the government. An incredible number of posters were generated, primarily for propaganda purposes, with the express agenda of bolstering the Cuban Revolution at home and exporting the idea of revolution abroad. The designers who created them (now often referred to as maestros by contemporary artists) were employed by state-run agencies such as the Committee on Revolutionary Orientation and later the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL).

Taken as a whole, these posters, bursting as they were with creativity and experimentation, represent a high point of 20th-century poster design, not only for Cuba but around the world. Yet their messages were tightly controlled. Private-sector advertising and promotion was essentially nonexistent. Only film posters produced by the state-run Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry, which controlled film import and distribution across the island, might be considered a kind of retail advertising. The idea of an individual producing posters for public consumption was practically inconceivable until the reintroduction of private business following the collapse of Soviet support in the early 1990s. It was the death of the USSR that signaled the rebirth of the Cuban poster.

On his first trip to Havana, Smith saw the work of this new generation of Cuban designers beyond the “Hallmark” posters they created for Sharing Dreams—work they were doing for actual clients. What he found made him realize his ideas about Cuban design were outdated. Further, he was struck by the similarities between their work and the work from Seattle. The Cuban designers he met were, consciously or not, leading the rebirth of the silkscreen poster. They initiated a resurgence in interest and production and were devoted to the history and lineage of the Cuban poster, yet they ached for outside contact and inspiration. Their work was obviously more personal in content and motivation than the propaganda posters of the past, and symbolic of an emerging trend in individual initiative.

The work of a design group called Cameleon struck Smith especially—these artists’ posters featured brutally rough imagery that could have been lifted verbatim from a sketchbook, often produced for their own personal exhibitions, sometimes printed in the middle of the night by state-run printers paid under the table. (Now there exists at least one private print shop, but then all print shops were state-run.) It was a DIY attitude that paralleled the explosion of silkscreen rock posters in Seattle in the mid-’90s.

Feeling this energy, seeing the lack of resources for designers in Havana and sensing their interest in the work from Seattle, Smith felt he “had to do something . . . to share our work publicly, open eyes to our common ideas symbolized by these posters.” So he began work on what would become The Seattle-Havana Poster Show. The exhibition, which premiered at Bumbershoot in 2007 and showed the next year at El Centro de Desarrollo de las Artes Visuales (CDAV) in Havana, paired posters by designers from both cities.

Now Smith has returned to Havana, talking to people about making a new exchange between artists of the two cities, perhaps one that includes music and film as well as posters.

But he has found a different Cuba than the one he last left.

Just about everything spills out onto the streets in Havana. The street is everyone’s yard. It’s where people fix bicycles and cars, where kids play soccer or kick around crushed-up cans. Couples make out on the steps. Produce carts park on the corners, selling heaps of finger-sized bananas. Exhaust from vintage American cars and Soviet Ladas hovers and clings. Music from wandering trios, playing hits from the Buena Vista Social Club, permeate the sounds of conversation, honking, bici-taxi bells, grumbling car engines, and the constant Taxi, amigo? Cohiba, amigo? And then there is the soft rock that completes the atmosphere, plenty of Air Supply and too many songs off the Dirty Dancing soundtrack.

And in the street people are talking. Many habaneros want to discuss politics and the recent news about the change in relations between the U.S. and Cuba. These Cubans say they are ready to be a part of the world, ready for change, ready for dialogue. One couple, upon learning that we are Americans, shakes our hands and says, “We are friends now!” A man who introduces himself as Antonio says he hopes this means that Cubans can have better access to medicine. Another man confesses he does not particularly like President Obama, and perhaps when all was said and done, nothing would change. “But,” he says, “at least we are talking.”

Edgar Moreira, a poster dealer we meet in the Plaza de las Armas, offers his philosophy. “America is a universe. It has the best of everything and the worst of everything. You cannot separate the blood from the shit—they both must exist in the same body.”

Eventually Smith and I come across a man asking for change near the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana. Spread out beside him are naked baby dolls, orixas out of the Santeria pantheon, and a statue of San Lazaro in a burlap shroud, suffering and holy, with his wound-licking dogs. A discussion about Saint Lazarus leads to talk about Cuba and the U.S. He asks us what we think of the recent announcement. We tell him it is a great thing—we are all for it. So is he. “Now things can get better for the Cuban people,” he says. We can begin to heal.

Saint Lazarus is Cuba’s saint. He represents healing, good health, and in some cases, military might. There are a few Saint Lazaruses in the Catholic canon, one having risen from the dead and another one stricken with leprosy, wandering around on canes—and with those dogs that constantly lick his wounds. For all purposes, they are the same: Saint Lazarus is about healing, a new start, a rebirth—about life resurrected.

It’s no accident that the simultaneous speeches by current Cuban leader Raul Castro and Barack Obama about normalizing relations between the two countries happened on December 17, the day many Cubans celebrate San Lazaro by making a pilgrimage to his shrine in the village of El Rincon, not far from Havana. “They picked that day [on purpose],” says Giselle Monzon when we meet with her and Michele Hollands. “And whoever wrote Obama’s speech knew the Cuban very well. I feel manipulated, but it’s good.”

Monzon and Hollands often collaborate on design projects—but as they never seem to stop laughing, it’s hard to imagine how they get any work done. Hollands is currently working full-time as a book designer for El Centro de Formacion Literaria Onelio Jorge Cardoso and freelancing for various agencies. Monzon is a freelancer, splitting her time between Havana and France, where her husband is working. Monzon worked for a time in-house at CDAV, where all the Seattle posters from Smith’s first show were donated, so she had access to a small but compelling collection of Seattle design books and posters. This collection influenced Monzon and Hollands—in particular the book Modern Dog: 20 Years of Poster Art.

In 2010, Hollands and Monzon created a poster for their own personal exhibit of posters at CDAV called “Paralelas.”

“We wanted to be revolutionary!” Monzon says of their poster and their exhibit.

“We wanted to do something funny and free and personal. It was an opportunity,” Hollands says.

Smith mentions that he recognized the influence of Modern Dog immediately in the “Paralelas” poster—specifically, Modern Dog’s “Care to Dance” poster, made for the Chicken Soup Brigade in 1997. Monzon looks a little sheepish. “They caught us,” she says to Hollands. What inspired them technically was the combination of photography and illustration—but even more evident was a Modern Dog attitude, a distinct brand of spontaneity and humor.

Monzon brought this new inspiration into the rest of her work, but found herself at a surprising crossroads between old and new when she was commissioned to make a poster design for South of the Border, an Oliver Stone documentary that examines seven Latin American leaders and the U.S. media’s biased perceptions of them. Working through the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematograficos (ICAIC), she created three versions of the poster—two made in her personal style and one that Monzon refers to as “old-fashioned.” This retro one, she says, was “very political. Black, white, red . . . like the OSPAAAL posters . . . with a claw . . . and this is finally what [Stone] wanted.” She says the film producers wanted a poster to align with Cuban poster tradition, a nod to the propaganda posters of the ’60s and ’70s.

However, her peers were unimpressed when she showed them her poster. “Everyone said, ‘Oh. Huh. You made that? We have many posters like this.’ ”

The poster was not at all representative of Gisele’s work, which adhere’s to the current wave of designer-driven Cuban posters that are highly personal and organic, and draw on global influence. The designer is largely in charge in these works, with the state demonstrating less and less control over the outcome—a shift which reflects the current changes in Cuba as a whole.

So it is not surprising that Hollands thinks the idea of change in diplomatic relations between Cuba and the U.S. is good, but there is some trepidation that nothing will happen. Or that change will happen, but it will be the wrong kind of change. “Please,” she says, “no McDonald’s.”

“Oh no,” Monzon echoes. “No McDonald’s.”

Claudio Sotolongo’s will to do seeps from his pores. He inspires this in others—often by directly telling them to do something. Introducing Smith to his fellow designers, he says, “Cards, people. Where are your cards? I always have to remind people to share their cards,” he tells me. I begin to feel bad that I do not have a card.

Sotolongo is a graphic designer who makes posters, teaches, and writes about design—his book, Soy Cuba, written with Carole Goodman, a U.S. designer who took part in the Sharing Dreams exchange, discusses Cuban cinema posters after the revolution. He says that once you begin to design posters, you can never stop. Their appeal is deeply personal—you get to express yourself as well as open a dialogue among the designer, the client, and the audience.

We walk along the old port in the sun-soaked air, the scent of fuel and salt on the breeze, barges anchored out in the bay. We turn down Calle Sol to a cafe that has a cat theme going for it: Cat-shaped cookies, cat portraits, cat figurines. We squeeze onto the bench behind the table. “This looks like Seattle,” Smith says, looking at the red painted walls, the chalkboard menu, Christmas lights. “What’s up with all the Christmas trees around here? Is that new?”

Sotolongo rolls his eyes and says that yes, it is all pretty new. “It’s the Pope,” he says. He goes on to express his distaste for the whole Christmas package, from trees to Santas to mangers. When the barista brings out our coffee, Sotolongo’s cappuccino is decorated with a cinnamon Christmas tree. He stares at it a minute, at a loss for words. Then he conjures up one. “Fuck,” he says.

“How have things changed in poster design?” Smith asks. One of his objectives here is to gauge the effect of The Seattle-Havana Poster Show on poster design in general. Sotolongo doesn’t bite.

“How have things changed?” he says. “It hasn’t changed!” They were doing silkscreen in the 1960s, and they did silkscreen in the 1990s, and they are still doing silkscreen.

What has changed, he says, is the economic environment in which the posters now exist. Foreigners are buying and reselling posters at a large profit. Seeing Cuban posters for sale online—“We do have Internet,” Sotolongo says, “sometimes”—for anywhere from $200 to $500 each makes designers and printers realize how much they’ve been undercharging.

This is no small matter. Designers may make posters out of love, the need to express oneself, and to contribute to a conversation. But to exist, they have to be funded by somebody—generally some cultural institution—because the cost of making a poster is very high. A run of a single poster, Sotolongo says, adds up to about 20 months of his salary. As a result, the prices are going up. And with those increased prices has emerged a growing market for bootlegged copies.

We leave the cafe and walk through the Plaza de las Armas, where a flea market takes place. Sellers set up booths of largely bootlegged books about Che, Fidel, and Ernest Hemingway; Cuban ephemera from coins and military medals to drinking glasses with Fidel on one side and ¡Viva la revolucion! on the other; and of course, stacks of posters—some genuine, some not. Genuine ones are stamped by the printer and often signed by the designer.

Smith buys a few posters for 40 to 100 CUCs, or convertible pesos, each. These prices are two to three times higher than they were during his last visit in 2009.

Sotolongo points out the bootlegged ones. “You see here?” He runs his finger along the lettering. “The detail is gone. The color is wrong.”

Prior to The Seattle-Havana Poster Show in 2007, people were still talking about the Cuban poster in terms of potential, says Pepe Menendez, who co-curated the exhibit with Smith. “People always talked about the poster in a nostalgic way.” Nostalgic feelings, he says, can be a kind of poison that makes people stay still and do nothing. “You just say, ‘Oh, we used to have those nice posters. We used to have those old maestros . . . ’ But this perception has changed. Most of the people today—critics, teachers, collectors—refer to the posters as a living body.”

Smith and I are speaking with Menendez in the backyard of the home he shares with his wife, designer Laura Llopiz, their two sons, and his parents in the Vedado neighborhood. Their black cat, Betun, named for shoe polish, rubs against our chairs.

“We made possible that people look at posters . . . as something that is alive. It’s not a dead body anymore . . . a luminescent, brilliant dead body. What a nice, beautiful dead body. What a nice corpse. And it’s not anymore like that. It’s a living thing.”

“A beautiful dead body,” Smith repeats. “The poster is rising from the dead.”

Menendez was one of the first designers Smith met through Sharing Dreams. He was immediately friendly and engaging, always smiling; his recognizable brand of humor always struck Smith as somehow American. He’s sharp, knowledgeable, well-traveled, speaks a terrific number of languages, and—via his work as art director of the famed cultural institution Casa de las Americas—has greater Internet access than most Cubans (for whom Internet penetration is still only about 5 percent). Born in 1966, he’s a link between an older generation of Cuban designers he met while studying at Havana’s Superior Institute of Design (ISDI) and a younger generation he’s helped mentor, particularly through the founding of the Friends of the Poster Club (CACa).

In Menendez’s view, Cubans have been trained by the system to “complain, not to do.” For example: “People complain, ‘Why is there no poster magazine?’ I say to them, ‘Well, why don’t you make one?’ ”

CACa, established by Menendez with fellow Casa designer Nelson Ponce, is a loose affiliation of Havana designers who gather every six months to review new posters. Each designer submits a new poster or two; they discuss, critique, drink beer, and eventually vote on the best poster. In a country known for an impenetrable, top-down bureaucracy and a litany of organizations that hold sway over everyone’s lives, CACa is an egalitarian collective where everyone has an equal voice and vote.

But this freedom extends only so far. The chances that a poster critical of the government would be printed are slim, and a designer wouldn’t create an overt one. Menendez tells us a story about a printer who was fired after printing oppositional materials after hours at a state-run print shop—for “political misuse of technology.”

When Smith asks if any oppositional posters were brought to the poster club these days, Menendez says no, but if someone did, he would let the artist display it just like anyone else. “Hopefully, it is a nice design,” he says.

Even if there were more oppositional messaging, it’s hard to say what effect it would have. As Menendez explains, poster-makers struggle to make an impact, something he describes as “our biggest death.” While progress has been made in reviving the Cuban poster among artists, designers, and collectors, the original intent of posters to communicate to a wider audience hasn’t come back, since posters are largely made for cultural institutions and aren’t posted on the street (a problem, Smith points out, that is replicated to a degree in Seattle, where the nicest poster for a concert is the one sold at the merch booth, not necessarily the one used to promote the show on the street). Until government postering restrictions are eased and they make the leap back to the streets, the poster rebirth could be headed back to the grave.

It would help if people had more opportunities to see posters, particularly more current ones, says Menendez. He would like a museum in Havana dedicated to posters. “This is a need,” he says. “It’s not just for me. It’s the responsibility of the state.” He’s been trying to convince the government to create this museum for four years, but so far nothing has happened.

Smith asks, “Will you take your own advice and just do it yourself?”

A thoughtful look comes across Menendez’s face. He smiles. “Maybe.”

Edel Rodriguez Molano, better know in design circles as “Mola,” comes into the lobby of Smith’s hotel smiling, headphones dangling around his neck, a portfolio of his recent work under his arm. He graduated from ISDI in 2006, just before the opening of The Seattle-Havana Poster Show. He too says that the show signaled the beginning of a new era of posters.

Asked how the show affected his work, he laughs. “I don’t know—because I am contaminated.” So many designers are doing posters these days, he has trouble pinpointing what exactly influences his work anymore. Influence and exchange are in the air he breathes.

We move aside the Christmas centerpiece so that Mola can spread out his recent work across the coffee table. He narrates each poster as he goes, describing what it was for and what he likes about it. He taps one. “This is for a political event.”

“I thought you didn’t do political posters,” Smith says.

“This was about political songs,” Mola explains, “the right political songs.”

Another poster, featuring a suspect lineup, uses American measurements. Mola laughs when Smith points this out. “We are all American now,” he says, adding, “We saw The Usual Suspects.”

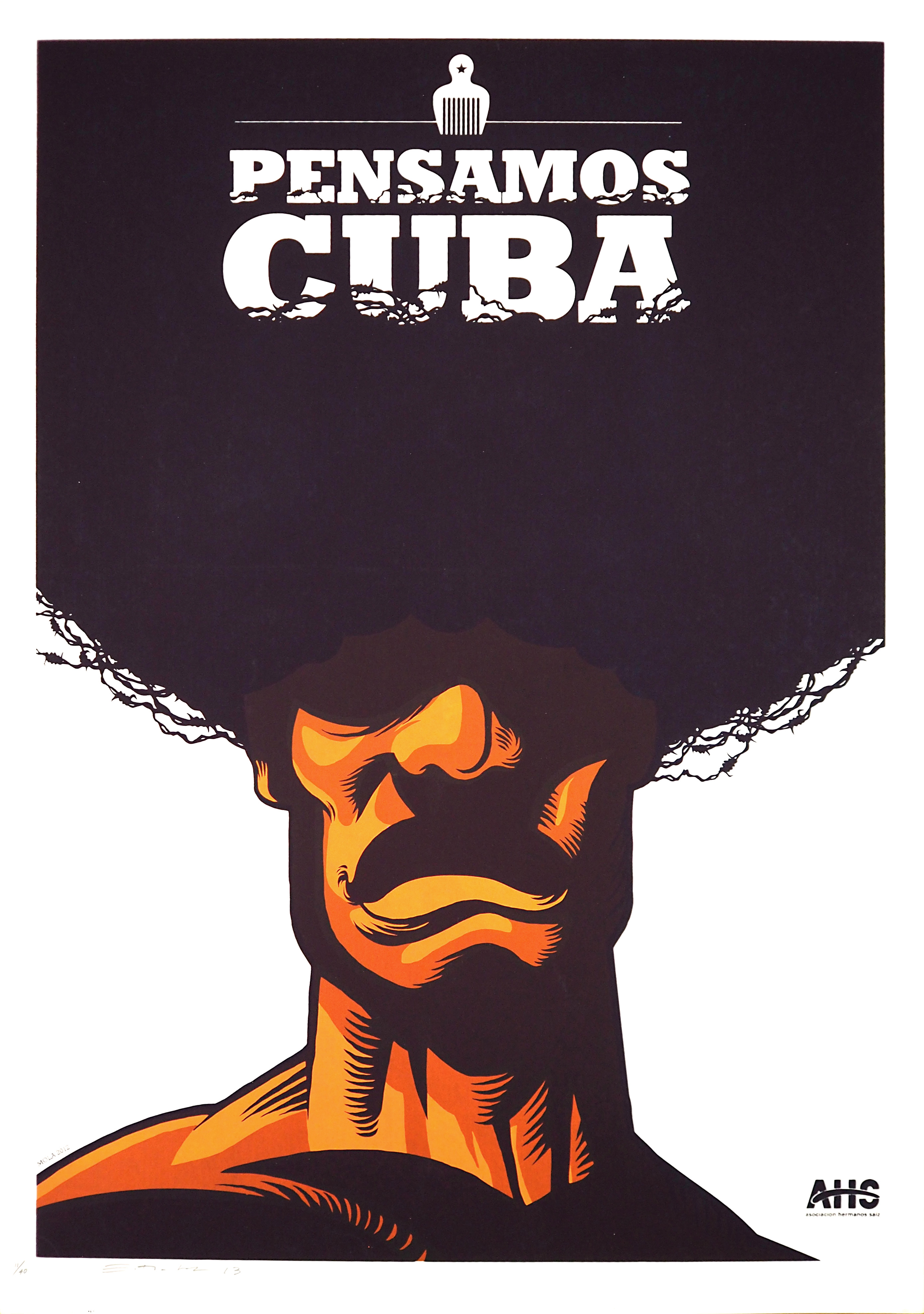

We pause a long time at a piece Mola made for the Asociacion Hermanos Saiz, a government-funded association of young artists, under the theme of Pensamos Cuba (“We think about Cuba”). He describes it as a “graphic essay.” It is an extremely personal work for Mola, but also a difficult one, because of the line a designer must walk between the personal, the state, the old, and the new. A designer can’t really cross the implicit lines drawn by the state. On the other hand, if the line isn’t crossed at all, there is a risk of looking “ridiculous” in the eyes of the graphic-design world as a whole. I am reminded of Monzon’s South of the Border design experience. “The limits,” Mola says, “are very complicated.”

The end result, though, is a stunning poster—the head and neck of a muscular brown man, his afro overtaking half the page, the words Pensamos Cuba wedged into the afro with a pick—loose strands of hair as barbed wire.

“We have a saying here,” he says. “A lo hecho pecho. It means stand by your work. This is yours—stand by your piece, be proud of it.”

Olivio Bonifacio Martinez Viera has always stood by his work, though his work is of a different sort than that of the current generation of graphic designers. A celebrated maestro who worked with the Committee on Revolutionary Orientation and then for OSPAAAL, he’s created hundreds of propaganda posters. Viera traveled to Africa, Nigeria, and the Congo as a designer to promote Fidel’s plan to export revolution to colonized peoples around the world.

With that resume, you might not expect Viera to be open to Americans, but he’s immediately kind and generous—even if he finds himself at a crossroads with Cuba’s current movement toward capitalism. When Smith and I ask him what he thinks about the changing economy and about designers who are opening small businesses, he takes a drag off his cigarette and looks out the little window of the hotel bar at the sea. We look out to sea with him, sharing his silence.

Half a cigarette later, he has an answer. “My perspective is not economical. I don’t think first about money. I first think as a designer, about the objective of design.” His entire career was spent in an economic and political system that allowed him to focus on his craft—type, image, color—not on financial reward, he says. And although he is happy about improved relations with the U.S., he believes everything outside of design—politics, economy—“is all the same shit.”

He says his initial reaction to the announcement by Castro and Obama was happiness. “It was logical. It’s very good to start a discussion. . . . This will be a more intelligent confrontation.” Cubans, he says, don’t have access to a lot of things that they need. Medicine, for example. He tells us about a hospital for kids with cancer, that they sometimes can’t get medicine. The medicine exists, he says, but not for Cuba.

Viera says he has always been for the people, and that means people in whatever country, even the United States. After hurricane Katrina, Viera felt compelled to do something to help. He designed a poster to be sold to benefit a nonprofit organization in the U.S. that was helping Katrina’s victims. Unfortunately, organizers told him they couldn’t get the funding to print the poster because he was Cuban. He told them to remove his name, that he didn’t care about credit or anything like that—he only cared about helping the people.

In Viera’s view, graphic designers can make a huge impact on the world. “Designers . . . and images are at the centers of power,” he says, but the new designers coming out of ISDI don’t realize it. “They embrace banality. They are too influenced by others.” He takes a sip of his espresso and shrugs. “But they think I am a dinosaur.”

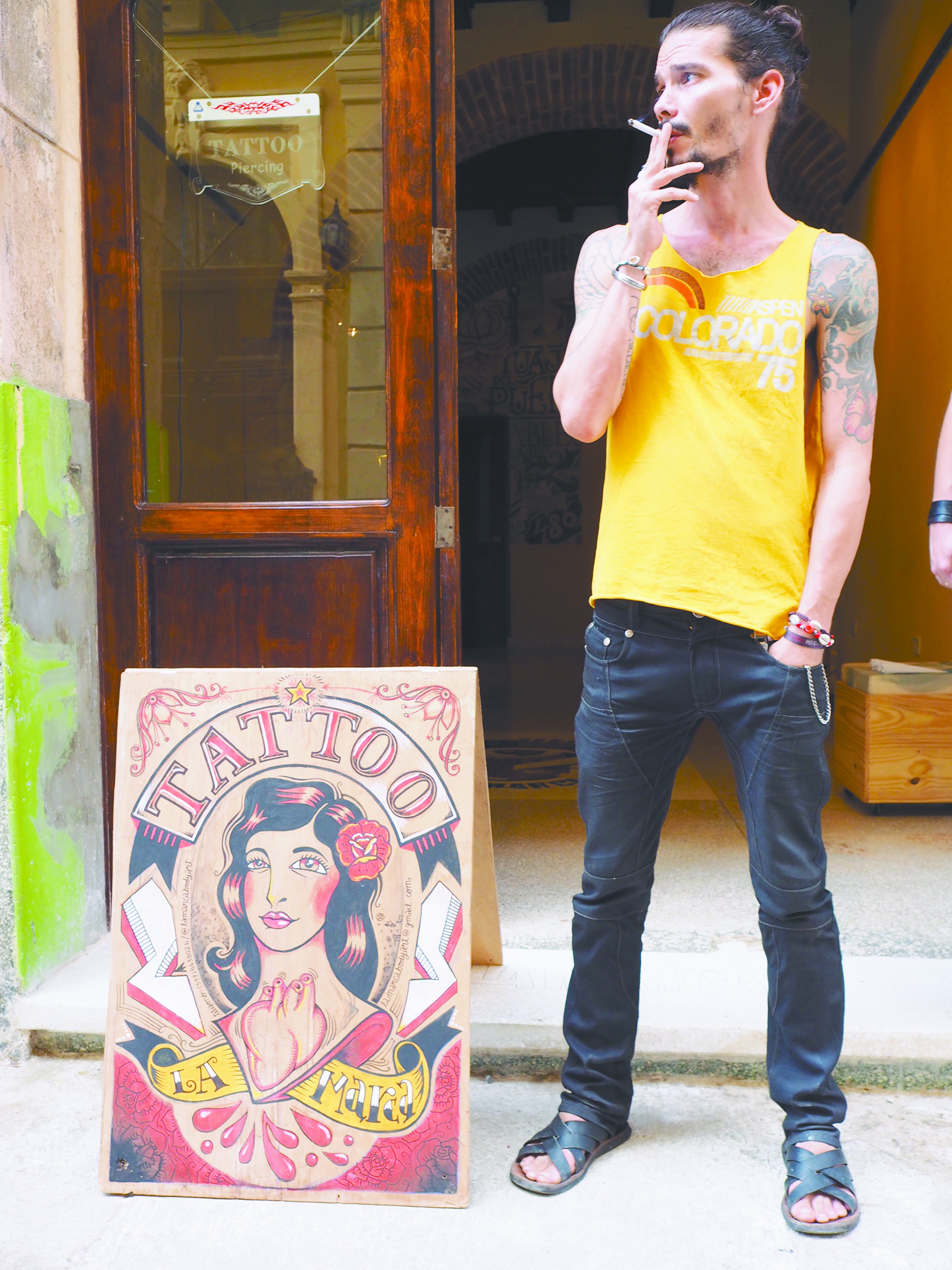

When Smith, Sotolongo, and I arrive at La Marca, a shop recently opened by designer and tattoo artist Roberto Ramos, we find a handwritten sign on the door: “Back in ten minutes.”

“It figures,” Sotolongo says. We peer into the windows at the mural painted on the back wall—a collage of letters, numbers, roses, and stars, crowned with a framed portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Laundry hanging from the building across the street reflects in the windows.

Ramos shows up in a sleeveless T-shirt and black jeans—a feathered creature tattooed on one arm, stars and ocean waves on the other—and gives us a complete tour of the place.

The shop is located in a more touristy section of old Havana—it gets a lot of curious looks from passersby. In the gallery space, located at street level, Ramos will exhibit posters by Havana designers that incorporate tattoos in some way. Though these posters will not be back on the street, they’ll be close to it. As both a gallery and a tattoo parlor, La Marca will attempt to bring design to the street, contribute to the neighborhood, and reach out across audiences.

Fellow designer Idania del Rio shows up at La Marca covered in sweat from a journey across Havana via taxi, bici-taxi, and finally by foot. She wears a white T-shirt that reads “ACTION CAUSES MORE TROUBLE THAN THOUGHT.”

When Smith met del Rio through Sharing Dreams, she was a part of a new generation of designers in Havana. A recent graduate of ISDI, she was open to collaboration and hungry for contact beyond the island. She acted as a guide and translator, helping Smith track down designers who didn’t have a phone or Internet, assisting with translations in the Seattle-Havana exhibition catalog, and creating the poster for the exhibition.

Having learned English from action movies, del Rio does not mince words.

“The poster was the least important thing,” del Rio says. More important was the contact with designers from the U.S., e-mail exchanges—having primary contact with people outside of Cuba.

“Idania is literally my poster child for The Seattle-Havana Poster Show,” Smith says, “a Cuban designer I wanted to help by giving exposure to her work. . . . She’s the one I thought of when I thought I can make a difference to someone in Cuba. I felt I had to personally do something.”

“That’s a very American thing,” del Rio says. “You’re all infected with I-must-do-something disease.”

We sit in Ramos’ gallery space and talk about the store del Rio will soon open—if she gets her merchandise out of Cuban customs. She had items made and T-shirts printed in the Dominican Republic, since it’s difficult to find supplies in Cuba. Her store will feature Cuban design as well as plastic toys typical of the island and straw hats from provinces outside of Havana. Del Rio also plans for the store to have a workshop space where designers can make their own prints.

“The simplest thing,” she says, “can be so hard here.” Her store, Clandestina, has been in the making for more than two years. Even the name caused difficulty because of its implications, referring to the time when private businesses were illegal and really did have to be clandestine. She says that while officials tried to discourage them from using the name, they didn’t say no.

“I’ve learned in this process,” she says. “In the beginning, I asked too many questions. Now I don’t ask—I just do.”

The street on the way to Clandestina is completely torn up. Cobblestones are piled along a trench, and bici-taxis, pedestrians, and cars try to squeeze their way through the intact side of the street. The four of us—Smith, del Rio, Sotolongo, and myself—navigate through hordes of uniformed schoolchildren on their way home. Garbage bins further narrow the street. I hold my breath against the stench. We walk past bloody fish heads, and I step in a pile of shit.

“In Ireland, that’s good luck,” I say.

“It’s good luck here too,” Sotolongo tells me.

We come to a fenced-off plaza with a dumpster in the center. Some of the buildings around the plaza sag; paint flakes off, revealing the gray beneath. Dust whirls in the wind. Del Rio and Sotolongo point out that the plaza is in the process of renovation. Signs on the fence show what it could be: tree-lined and lush with cobblestone pathways, the buildings surrounding it scrubbed, repaired, and repainted. I mention that it looks pretty nice—though, based on the plaza’s current state, it is hard to imagine the picture ever becoming reality.

“Yeah, they’ve been restoring it for, like, 10 years,” Sotolongo says, laughing. “And it never changes.”

We turn away from the plaza and walk toward del Rio’s store. Clandestina stands out on the street like a kind of phoenix rising from the ashes—a restored colonial building, painted clean white, with beautiful wood-framed windows and doorways.

The inside is equally renovated and polished. She’s painted one wall with melting multicolored hearts and another with a silver palm tree. High on a white wall is a message in black paint: 99% diseno cubano. It is all empty space now, but she shows us where the merchandise will go, where the workshop will be.

From the balcony of her office-to-be, we take turns checking out the view, looking out onto the street, the plaza, people walking by. I wave to a woman out on her own balcony. From here, I can imagine the plaza restored and lined with trees. I see that it could happen, that what seemed dead could be resurrected. It would take a lot of work, determination, and maybe even a miracle—but it is possible. Anything is possible. E

news@seattleweekly.com

Chelsea Bolan is a Seattle writer. Her first novel, In the Place of Silence, will be published in spring 2016 by HarperCollins Canada.