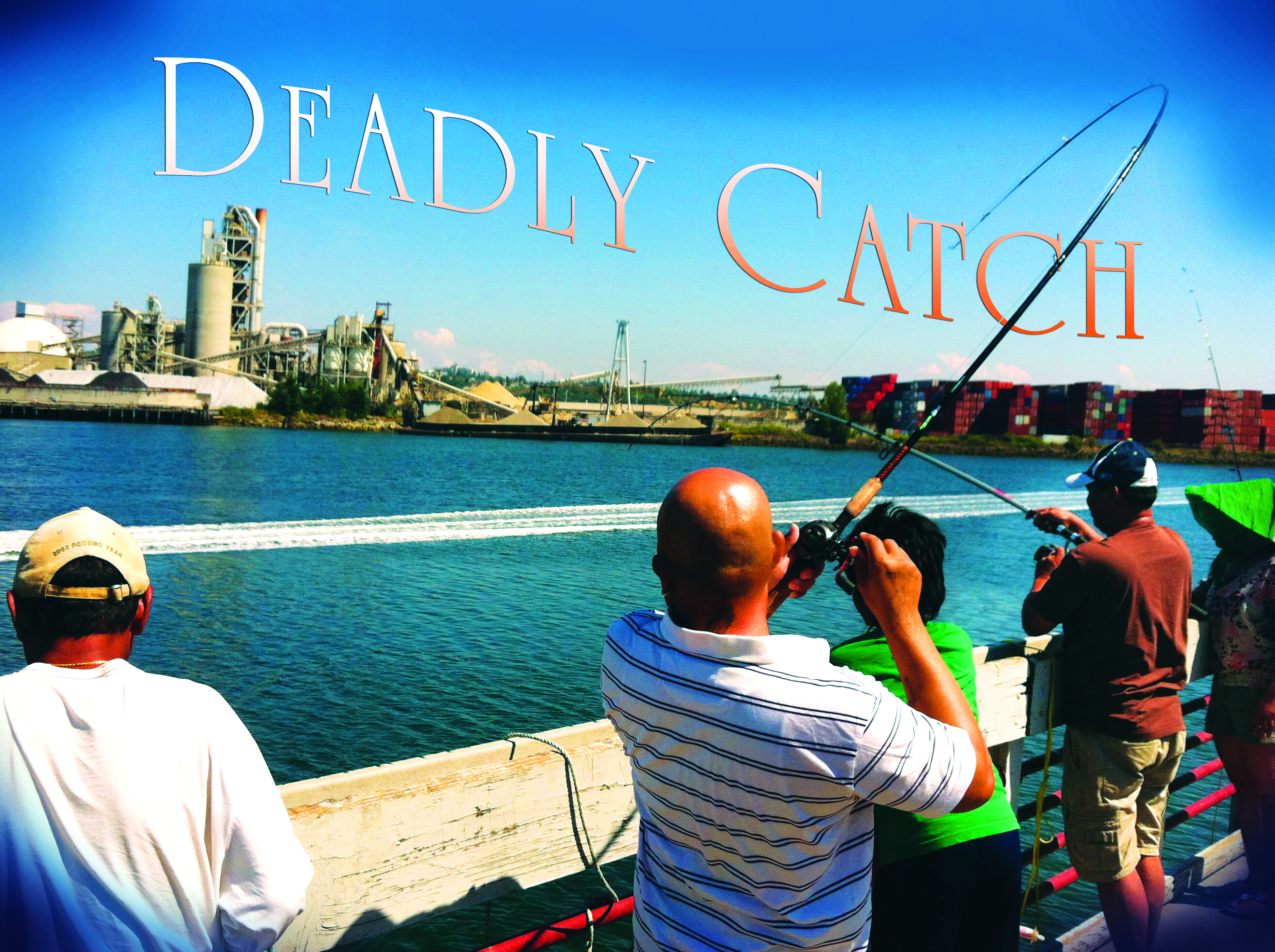

As I discuss in this week’s cover story, the EPA is preparing to initiate the most concerted and expensive effort yet to clean up Seattle’s only river, the Duwamish.

More than 100 years of breakneck industrial growth that played a vital role in the WWII war effort and Seattle’s rise as an economic powerhouse has left the river a Superfund site, meaning it’s considered one of the most contaminated places in the country.

The cleanup itself will focus on sediment in the river, but that’s only one part of the overall strategy to get the river, and the fish that live in it, clean.

Under the oversight of the state Department of Ecology, the city of Seattle, King County and other municipalities that line the Duwamish and Green rivers are spending hundreds of millions of dollars to keep new contamination from reaching the river and thus reversing the work of the Superfund cleanup.

The way they do so are many. The City of Seattle is continuously tracking down old storm drains that still harbor containments from a time when the use of PCB and other toxins weren’t as strictly regulated. When workers find a source, they dig up the storm drain, scour out the sediment, and then ship it off for treatment. The Department of Ecology has 18 clean-up sites that focus on heavily contaminated areas along the Duwamish and Green. And this still just scratches the surface: PCB, a carcinogenic chemical that was widely used in paint before it was banned in 1979, can still be found on many old buildings around the Duwamish. With every rain fall, that paint can flake off, run into storm drains, then deposit at the bottom of the river.

“There’s probably about 10,000 buildings that have the potential to have PCB material on them,” said Dan Cargill, Source Control Project Manager with Ecology.

Just one such example: That brightly colored old Rainier Building. Below its brilliant yellows and oranges is an old coat of paint that was found to have 240 times higher than the level at which the state requires removal.

When plans for the EPA cleanup were announced, environmentalists led by the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition were disappointed that this so-called “source control” work weren’t included in the plan, saying it would give the state government more leverage to force businesses to prevent pollution from their business sites to the Duwamish. They’ve asked the EPA to reconsider.

The city of Seattle also has extensive outreach to businesses in the Duwamish drainage to make sure they are following strict rules about what can and can’t be poured into city storm drains.

It was to get a better grasp of this work that I took a ride-along with Michael Jeffers, a city inspector whose job it is check in on businesses through Seattle to make sure they aren’t dumping toxic chemicals or other pollutants into the streets.

During the ride-along, I found myself in the garage of one of the oddest business enterprises I’ve ever encountered in Seattle. A lot is strange about the Mount Baker business. “In the past there have been problems with drugs,” Jeffers says by way of bracing me for a scene. It is a car wash with no electricity and an on-site freelance auto mechanic, a man with whom Jeffers had a slight language barrier. As we are trying to communicate, the owner, a man named David, rolls up on an old green bicycle, sucking on a sucker. Pulling the sugary treat out of his mouth with a slurp, David begin debating with Jeffers before the inspector has said a word.

“There was an inspector here just last week!” the man says, clearly frustrated by all the hoops he has to jump through just to run a business not even hooked up to the electrical grid. “We ain’t using no chemicals! We don’t do it like that any more!”

Jeffers, whose smile seems to be part of his work outfit, is clearly disposed to the good-cop form of persuasion, and explains that chemicals or no, the shop was set up in a way that could easily seep contaminated water into the storm-drain. Fines are rare, Jeffers later tells me, with the department only issuing 30 every year, and only a fraction of those being paid, with the rest waived when the owners commit to better practices.

As it becomes clear that Jeffers’ visit is more informative than regulatory, David becomes less defensive. “Right now, we’re barely getting business,” David confides. “Times are tough.”

Jeffers sympathizes, and it seems sincere. Later he tells me: “You need all of these businesses,” he says. “You can’t put them out of business. They serve a purpose. It’s just a matter of pushing them in the right direction.

“The message we try to get across is, ‘We’re spending all this money cleaning up the Superfund site. We don’t want to pollute it again.’”