Let’s say you’re a bookish young man at a university. You meet another student who’s a lot like you in some ways and has the same sort of taste in music. You start a band; you make a couple of primitive, playful singles, one of them about having a crush on an actress in old movies, another about having a crush on a girl who works at a bookstore. Your aim is true but not high. Eventually, you understand, the little differences in temperament between you and your friend will be much bigger differences. You don’t expect that you’ll still be playing and singing together 27 years later—you can’t.

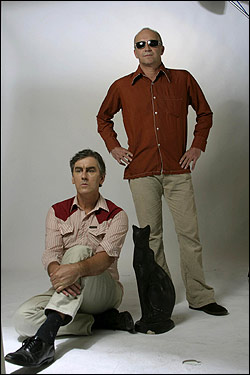

That’s exactly what happened with the Go-Betweens, though. Formed in late 1977 at Queens University in Brisbane, Australia, by Robert Forster and Grant McLennan, they spent most of the late ’80s chasing fruitlessly after more fame than they were going to get. By then, it was already clear that they’d become vastly different songwriters: Forster a brainiac snarler, McLennan a meditative aesthete (“I recall a bigger brighter world/A world of books and silent times in thought,” he sang in their best-known song, “Cattle and Cane”). They made a series of elegant, bright records and finally gave up at the end of the decade.

But the problem was in their goals rather than in their compatibility. After a string of solo records that mostly demonstrated how much they needed each other, McLennan and Forster drifted back together, beginning with a few reunion shows in 1997, and in 2000, they assembled a new and more modestly pitched Go-Betweens. Oceans Apart (Yep Roc) is the third album by the band’s current incarnation, and it’s got a theme that’s entirely appropriate for them: distance, travel, and correspondence.

Forster opens the first song in the language of a dashed-off postcard: “Just pulled out of a train station we’re moving sideways/I’m sitting here with three other people in the carriage.” What rhymes with “carriage”? Well, “marriage”—but he doesn’t rhyme that line at all, even though he rhymes “skyscrapers/sandwich maker” and “night/bright/flight/night” elsewhere in the song. There’s crackling emotional distance here, not just physical distance.

So McLennan counters it with his own song about being in motion but emotionally close, “Finding You”: “What would you do if you turned around/And saw me beside you/Not in a dream but in a song?” Almost all of the characters on the album are moving from somewhere to somewhere else, even if they don’t know where; they’re trying to live something like the life of the mind, even if they’re not sure how to make it rewarding. (The Go-Betweens’ T-shirt for their current tour is a line from the new record’s “Here Comes a City”: “Why do people who read Dostoevsky always look like Dostoevsky?”) It’s a life you’re stuck with once you choose it, and it’s not a life that’s guaranteed to bring you happiness. See, for instance, the subject of Forster’s “Lavender,” who’s “been to Sydney once, no more” and is now thinking about moving to Tasmania: “Everybody said that she’s good in bed/Other people said that she’s well read.”

The sound of the Go-Betweens’ records changes a little with time and fashion, but Forster and McLennan found their stylistic niche as performers with Before Hollywood, 23 years ago, and have stayed precisely there ever since. It’s parlor rock, very physical but rather frail even when it gets loud: Their guitar playing emphasizes the impression of hands moving across strings, and the rhythm section’s pulse is meant for sitting down rather than dancing. And for all their talk about travel, these songs are set in the same places and mental space the band has always occupied. If Forster and McLennan are writing about rushing around the world on trains and ships, it’s in an attempt to get some kind of perspective on their own territory.

Oceans Apart is an album about trying to become comfortable in stasis, but it’s also about nostalgia and even nostalgia for nostalgia. McLennan’s “No Reason to Cry” is addressed to someone he hasn’t talked to in 15 years; his “Boundary Rider,” a vision of the Australian outback, recalls the setting of 1982’s “Cattle and Cane,” which was itself about remembering a place and an emotion. Forster’s “Darlinghurst Nights” is the central song of the album, a half- embittered recollection of his youthful ambitions that gradually accumulates instruments and volume over the course of six minutes or so. “Marjorie and Kim, Andy and Clint/Debbie, Bertie, people came and went,” he sings, enunciating the names much harder than he has to; then a brass band strikes up and carries him out.

It’s a mysterious song, and Forster doesn’t fully explain himself. There’s at least a hint of private language about every song on the album, an assumption of shared context. Maybe Forster’s primary audience for his songs is McLennan, and vice versa; maybe they know that what their lyrics elide over is part of their allure. They have the tone of letters addressed to somebody you’ve known for 27 years, somebody with whom you have in common only the fact that you were a team against the world once, which means you always will be.

The Go-Betweens play the Triple Door with Dolorean at 7:30 p.m. Thurs., June 16. $17.50 adv./$20.