Mo stands still on a worn chest in the middle of a living room. Looking down in terror, he sees his memories dance around him in an increasingly intense and fast-paced re-enactment of his trauma (as well as the preceding 30 minutes of the play). Visibly distressed, Mo descends from the chest and begins to undress, his emotional state deteriorating with every step.

Every Five Minutes, written by experimental Scottish playwright Linda McLean, follows the story of Mo (Tim Gouran), a man who has suddenly returned home from 17 years of torture and isolation, the reason why unknown to the audience. His trauma rules his consciousness: a space that abruptly jumps from scene to scene, shuffling his hallucinations, dreams, and reality. He arrives to a “Welcome home” party with his wife and two of his best friends from his old life—but the party is disorienting and fragmented. The audience is pulled through a narrative pockmarked with strange glitches, from scenes of torturers dressed as clowns to flashbacks of Mo’s childhood memories with his alcoholic mother. The people that appear in his hallucinatory dream space constantly switch roles, adding to the confusion both he and the audience experience. Washington Ensemble Theatre’s production of Every Five Minutes successfully balances the tender and brutal experiences of PTSD through this engaging spectacle, prompting an emotional audience response as regards state-sanctioned violence.

In one striking scene, imprisoned among three large mirrors with light flooding from above, Mo talks to God about the freedom of sleep. The balance of Mo’s vulnerability alongside the brutal mirrors and lighting elevates the intensity of his deep desire to be heard. The design skills of Ahren Buhmann (set work), Reiko Huffman (painting), and Evan Anderson (lighting) balance the visual experience of the soft and severe inner workings of Mo’s mind.

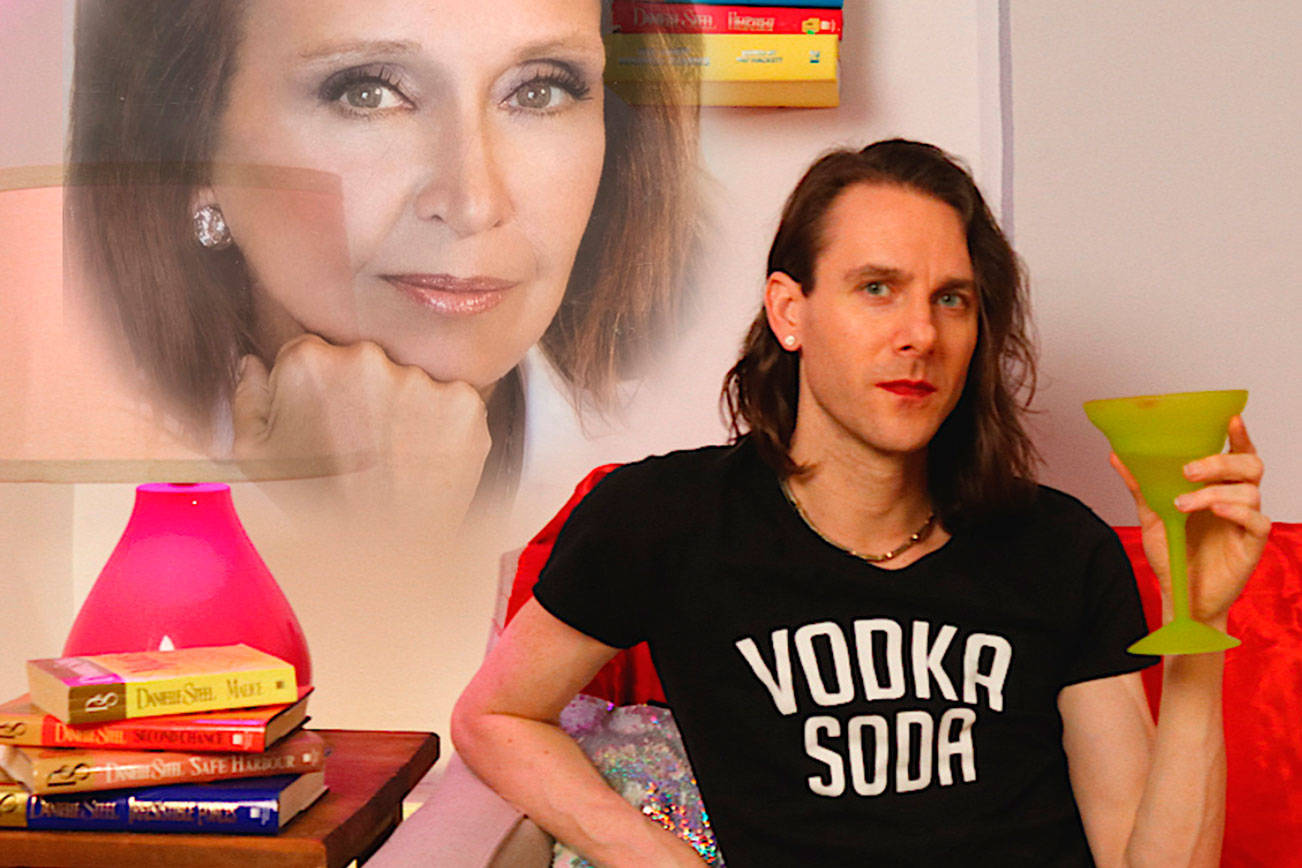

In another scene, surrounded by paintings that look as though they were bought at Target, Mo’s good friend Rachel (Jonelle Jordan) casually leans back into a mahogany chair holding a half-empty glass of red wine, complaining about her issues with voice mail and her land line. Her friends, aside from Mo, respond with empathy, validating her complaints. This snapshot of the dominant culture of the white middle class encapsulates Rachel’s right to comfort, one that many white folks in the U.S. feel they deserve. In light of the obvious trauma Mo is experiencing, Rachel is unable to step outside her own issues and deeply engage with his emotional complexity. Jordan’s strong characterization reveals a significant theme of the play: the way in which dominant white culture keeps the majority of whites complacent about the constant violence that the U.S. government is engaging in, whether psychological, emotional, or colonial.

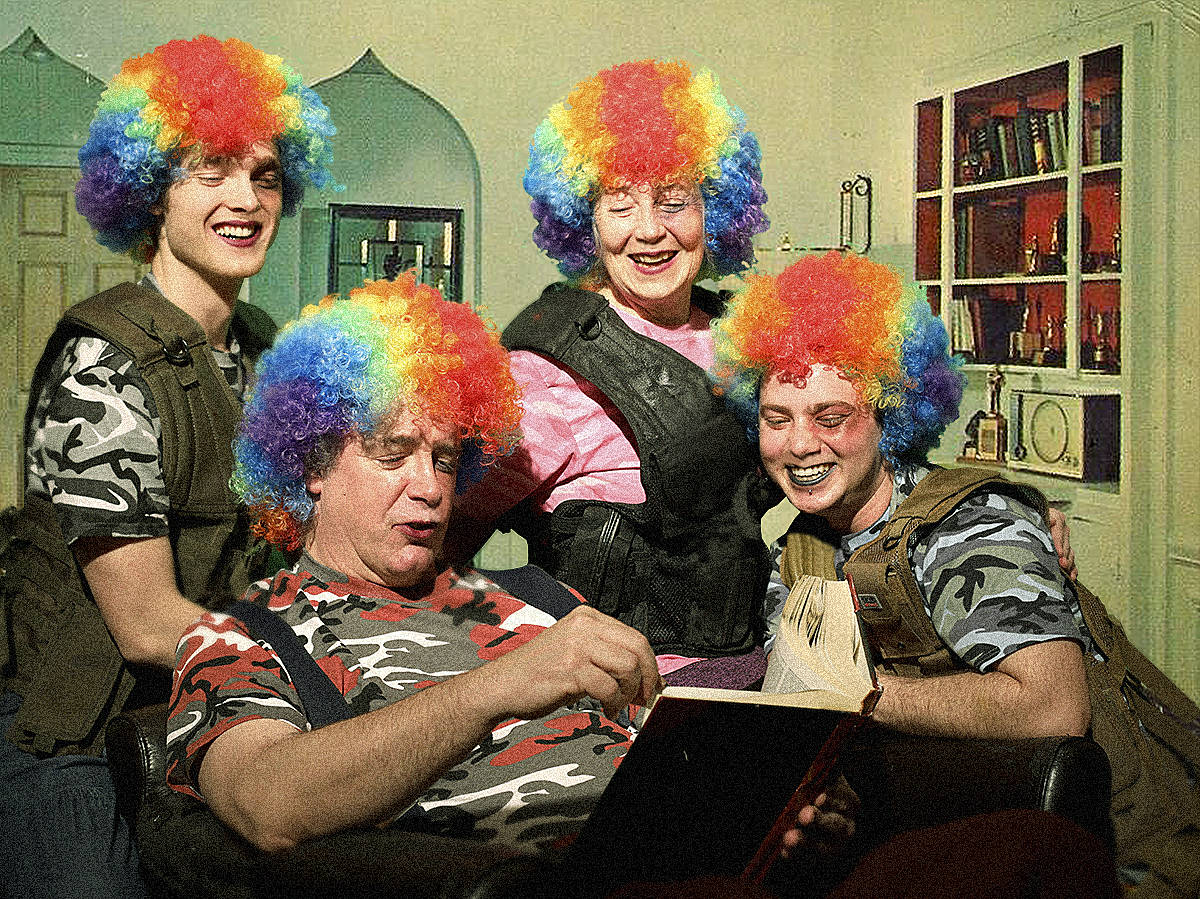

Mo and the audience are jolted out of reality as two terrifying clowns appear in his wife’s living room. These clown-demons (Nick Edwards, Tré Calhoun) are central to Mo’s hallucinations. Near the end of the play they sit with an unconscious Mo, giving him a sponge bath in the tub they had previously attempted to drown him in. Looking at each other, one clown asks, “What will they say about us?” in reference to their role as torturers. “They will say we kept him clean,” replies the other. This scene, like numerous others, emphasizes the effect that water torture had on Mo during his time in prison. Mo’s story reminded me of a contemporary political moment, in fact: Donald Trump’s campaign promise to bring back waterboarding and “worse” forms of torture, a promise his own nominee for CIA director, Mike Pompeo, opposes. The pain in Mo’s eyes during the scene is poetic and heartbreaking. I could see the injustice of torture being inflicted upon Mo, and fought back the urge to run onstage and intervene.

Every Five Minutes engages directly with fear and violence, and in doing so, the audience is made to engage as well. From our seats, we are invited to reflect on our own role in passively supporting or actively fighting pain inflicted upon individuals in the name of state control—a question that could become even more pressing in the years to come. 12th Avenue Arts, 1620 12th Ave., washingtonensemble.org. $15–$25. All ages. Showtimes vary. Ends Mon., Jan. 30.

stage@seattleweekly.com