What is most distinctive about Holly Eckert’s new piece, Coming Unglued (at East Hall through Saturday, March 29; call 206-297-1844 for more information), is the thing that is in some ways the least discussable: the fact that she is epileptic and performs this work about epilepsy not knowing whether or not she will have a seizure during it.

On one level, this information doesn’t make any difference at allunexpected things happen all the time in the theater. One of the primary elements that makes a live performance different from a recorded one is the possibility of chaos; the distinction between the random choices made in some improvisation and the arbitrary action of nature is a matter of degree. But in opening a door to these possibilities, an artist takes the chance that she will become the topic of the performance: Are we watching the dance or watching her disorder?

Eckert, it seems, would like us to watch the dance, but since she incorporates text and images that refer to the electrical brainstorms and personal disruption of epilepsy, we’re never far away from the topic. In two different monologues, Eckert tells the story of the car accident that triggered her diagnosis and her experiences of seizures. A variety of stories from other people describing their own medical histories fade in and out of a recorded soundtracka litany of surgeries, broken bones, and visions. The biochemistry of their seizures is combined with their almost metaphysical feelings of wonder and peacethey speak of seeing a “beautiful aura” that is simultaneous with a fall down the stairs or a call to 911. Mandy Gulla’s visual art, glowing watercolors that she paints on top of anatomical drawings during the performance using an overhead projector, reinforces the visionary imagery.

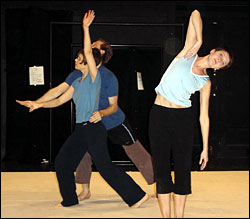

Unfortunately, the linking element among all of the storiesthe dancing itselfis curiously subdued, with neither the flowing grace of the woman who sees Christ during her episodes or the agitation of the man who falls down the stairs at the Kingdome while the crowd sings the national anthem. The movement is sometimes interlaced with small tics and facial grimaces but is mostly like other pieces Eckert has made: long abstract phrases performed with moderate energythe dancers don’t jump too high or fall too hard (in some ways they resemble a group of people trying to blend into a crowd). Perhaps this is all meant to reflect Eckert’s description of her own “partial complex seizures” in which she seems to “go away for a time,” looking confused or out of place. The pedestrian quality of the energy feeds this ambiguity, though, so that you watch Eckert and wonder, in a variation on the old Clairol ad, “is she, or isn’t she?”: You think, mostly, that she isn’t having a seizurebut is not knowing a part of the dance?

In her infamous 1995 New Yorker essay, “Discussing the Undiscussable,” Arlene Croce told how she refused to see Bill T. Jones’ Still/Here, a work incorporating videotaped interviews with AIDS and cancer patients, because she felt the dance was more therapy than art and that her objectivity was compromised by the reality of the patients’ illnesses. The furor that her non-review generated brought up all kinds of accusations from racism to elitism, but came down to the question of whether artists can use materials from the most fragile places in their lives. The answer, of course, is yes, but if an artist amplifies a topic from her life, she risks having her life itself overwhelm the art. It involves a balancing act that Eckert has not fully mastered here.