A story is never really over. Yet, deadlines dictate that we all must let go at some point. Here at Seattle Weekly that is generally a peaceful process, though sometimes editors must tear a story out of the reporter’s clutches in order to send it on to the copy desk, through production, and to you in a timely manner.

Always happy to return to the stories they were forced to abandon, our reporters reached out to the subjects of 10 of our cover stories to see what has happened in the days, weeks, and months since the ink dried.

Yoga Behind Bars Stretches Out

In August 2015, 10 incarcerated men with long or life sentences were transferred from their respective Washington state prisons to the Stafford Creek Corrections Center, near Aberdeen, for six months. The goal: to train these inmates to be yoga instructors (“Freedom Within,” January 13). For Yoga Behind Bars, the Seattle-based nonprofit that created the program, it was a way to help these men heal. “One day,” Seattle Weekly reported in January, “YBB staffers would like to expand the program to women’s prisons, too.”

As of November, they have. The second cohort, composed of nine women from the Washington Corrections Center for Women near Gig Harbor, have begun their six-month training and will graduate in early April. Participants so far report feeling that the practice is “literally the best thing my body’s felt in a long time” and that it’s been a way to learn about themselves—to find their own voice. “I have not done that, ever,” says one. “I have never felt valued enough to do that.”

Meanwhile, nine of the original 10 men are currently either teaching or co-teaching yoga classes at their respective facilities, says YBB executive director Rosa Vissers. Greg Steen, a first-cohort graduate and former Seattle resident now serving a life sentence at Clallam Bay Corrections Center, tells Seattle Weekly he has been keeping busy with a slew of projects, including a memoir, a podcast, organizing for prison reform via the Black Prisoner’s Caucus, teaching weekly yoga classes with a fellow cohort grad, and creating the curriculum for a class on the history of yoga. He’d like to teach one on meditation, too—something he began back in 2011, two years into his life sentence, which he hopes will be commuted by the governor one day. SARA BERNARD

Artists Continue to Fly South

At the beginning of the year, a worrisome trend had emerged in Seattle: Local musicians were packing their bags and moving out of the city. At the time of our story on the phenomenon (“Vanishing Acts,” January 20), surf-rock outfit La Luz and R&B artist Shaprece had already headed for L.A., while Stasia Irons of THEESatisfaction (which would break up later in the year) had just returned from a long stint in New York, hoping to head back east soon. While Irons seems to have anchored herself in Seattle since then, becoming the new host of KEXP’s Street Sounds, she was only able to do so after Seattle lost that show’s prior host, local hip-hop aficionado Larry Mizell Jr., who, you guessed it, left for L.A.

As 2016 wore on, the City of Angels claimed a few more of Seattle’s arts angels—superstar record producer and shoegazer Erik Blood, along with his partner (and one of the most prolific contributors to alt-comics newspaper Intruder) Joe Garber. Fellow Intruders followed suit after the paper called it quits in July, with Brian Dionisi joining Garber in L.A. and Fantagraphics-published Josh Simmons leaving for Portland. Soon after Mizell left KEXP, another of its legacy on-air hosts, Kurt B. Reighley, aka DJ El Toro, left for Tuscon with his partner, celebrated artist and clothing designer Mark Mitchell. Both had lived in Seattle for 30 years. Reighley’s parting message to KUOW? “For us, we simply couldn’t afford to live here anymore.”

As for our cover subjects in La Luz, in May L.A. Weekly ran an article entitled “La Luz Just Moved Here From Seattle, But They’re Already One of L.A.’s Best Bands,” noting “It’s surprising that they aren’t from here in the first place.” Sigh. KELTON SEARS

The $60K Grind Gets a Little Easier

At the beginning of the year, the University of Washington’s Housestaff Association was in a tough spot. As we reported (“$60K Struggle,” January 27), the union represents medical residents who were at the time struggling to survive financially because of Seattle’s high cost of living—despite annual salaries near $60,000. Fifth-year resident Andrew Korson said he had to put his tuition loans into forbearance, where they accrued interest for years. “I wasn’t expecting to come into residency and make a lot of money,” he said. “What I [also] wasn’t expecting was that during my five years here, my rent would go up 30 percent.”

In October, after two years of negotiations, the union and UW agreed on a contract that will mitigate a lot of the ills our story outlined, mainly by bumping up resident pay and benefits. According to a union press release, pay for residents and similar apprentice doctors will increase 3 percent annually. They will also receive a housing stipend of about $1,000 each year, an annual $750 transportation/parking stipend, reimbursement for licensing costs, a grievance procedure, and a bunch of smaller benefits, including the right to moonlight for extra cash and some thinly stretched funding for child care. However, some of the funding for those goodies has been yanked from other funds for residents, like conference travel money, according to the Housestaff Association’s Katie Benziger.

What the new contract does not include is paid maternity leave, a subject highlighted in our story by Benziger, who as a senior resident in 2012 maintained her regular schedule late into a pregnancy because UW does not offer paid maternity leave. The stress led to potentially fatal complications, and Benziger underwent a C-section a month before she was due.

Nonetheless, she says, the new contract is “a start.” CASEY JAYWORK

Climate Resistance Grows (Up)

Climate change, according to die-hard climate activist Michael Foster, founder of the Seattle chapter of the kids’ group Plant for the Planet, is a “time crime.” We won’t know quite how much damage we’ve caused until decades down the line, when our children and grandchildren are the only ones left to deal with the consequences. That was the backdrop of our story about a group of whip-smart and passionate 8- to 14-year-olds who have been planting trees, petitioning, and advocating for climate-change solutions (“Sprouting Resistance,” February 10).

The kids remain undaunted in their mission, and the group has grown, welcoming 54 new members in 2016. They’ve spoken at events and rallies and meetings all year long, from NW SolarFest in Shoreline to Bill McKibben’s talk at Town Hall. They’ve sent letters to the Department of Ecology and a thank-you card to the Gates Foundation for divesting some of its assets from fossil fuels; they participated in an Earth Day flash mob and made a video for Standing Rock. And they’re always planting trees. On December 10, they planted five redwood saplings in Jefferson Park, as part of a project to bring 300 redwoods to 26 sites around Puget Sound.

And yes, eight of these kids are still plaintiffs in the highly publicized lawsuit that petitions the Washington state Department of Ecology to enact a carbon rule stringent enough to protect their constitutionally protected right to clean air. Foster, meanwhile, continues to give talks about climate change to grade schools in the region. He’s looking to pass the torch now, though, to make room for new leadership and to focus on more radical climate activism: Foster is among the five activists now facing steep felony charges for closing emergency shutoff valves on tar-sands pipelines.

Several adults are ready to step up and even more kids are ready to do something. The group’s new president, 13-year-old Athena Fain, says her goal for next year is to make sure her tone is positive when she makes speeches. “I don’t want people to feel negative,” she says. “Now is definitely not the time.” SARA BERNARD

After Berner

In advance of the Washington Democratic caucus in March, we met with a number of Bernie Sanders supporters to better understand why he was so popular in our city (“The Bernie Paradox,” March 23). With all that has transpired since the caucus, we checked back in with a few Sanders supports to see how they’re doing in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s eventual victory over Sanders and Donald Trump’s eventual victory over Clinton.

The Rev. Dorinda Henry says she was disillusioned with the Democratic Party after Clinton’s nomination, echoing many Sanders supporters across the nation who felt that the party had conspired against their candidate. She says she was planning on casting a protest vote against both Clinton and Trump, but was persuaded to do otherwise. “I heard both Michelle and Barack get out on the campaign trail for [Clinton] and talk about his legacy, and at that point I said, all right. I was reluctant, but I heard them, I respect both of them, and I definitely wanted to make sure President Obama’s legacy got entrenched and remains.” Today, Henry says, she believes it is incumbent on progressives—especially people of color, like herself, and LGBT people—to run for office. “He [Trump] ran a campaign of racism, and people from those backgrounds need to meet him in the body politic and say, ‘We are not going back to a time before the 1950s.’ ”

Another supporter, Kim Naranjo, seemed less hopeful. She said in an e-mail that she went and protested at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in “100-plus degree heat.” “The broken United States election system knocked me down. Hard… . However, I have no regrets about traveling nearly 3,000 miles to make my voice heard.”

Today, she says, she feels “jaded.” “I realize that, unbeknownst to me, my voice has been silenced; probably a long time ago by a system that gradually and insidiously morphed into fascism while lulling us to sleep.” DANIEL PERSON

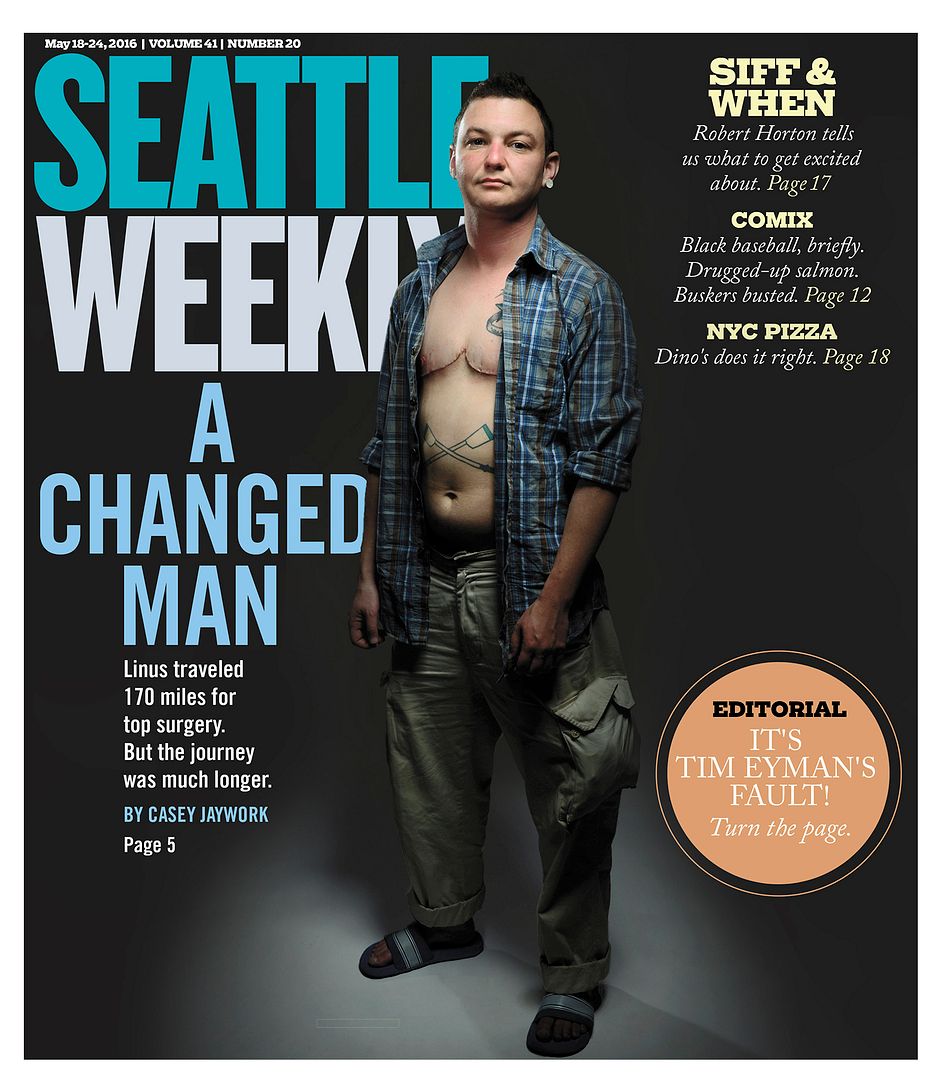

Top Surgery Still “Awesome”

In April, Seattle Weekly rode along with a Seattle transgender man named Linus as he traveled to Portland to undergo chest-reduction surgery (“A Changed Man,” May 18). Eight months after surgery, he’s still elated at his newly flat chest—no more chest binder, no more sneaking around when changing clothes. “After [the surgery] happened I kind of expected it to stop being so awesome and I’d get used to it,” he says. “But it’s still pretty awesome.”

Recovery wasn’t a big deal, says Linus. “People get weirded out sometimes because it’s like ‘Surgery!’,” he says, “but you feel kind of crappy for two weeks and then it’s done. It’s really not that big of a deal” in terms of the physical toll. “When I had mono, I was way sicker.”

As we reported, Linus’ ability to make his way to a surgeon’s table was thanks in large part to the work of trans activists leaning on companies, courts, and state Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler. After more than a decade of hearings, lawsuits, and letters, the Coalition for Inclusive Healthcare convinced Kreidler to rule in April 2014 that companies could no longer specifically exclude gender-transitional health-care services. After that letter, Obamacare’s expansion of Medicaid, and a lot of red tape, Linus finally got his surgery.

Will other patients be able to do the same thing? Yes, at least for the foreseeable future. The President-elect and Congressional Republicans are bent on repealing Obamacare, but a spokesperson for Kreidler’s office says even if that happens, the protections for transgender patients outlined in Kreidler’s letter will stand because they’re “so clearly embedded in state law.” CASEY JAYWORK

Bars Keep Breaking the Rules

In late May, the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board issued a $151,000 fine against Anheuser-Busch In-Bev, the brewing giant behind everything from Bud Light to Space Dust IPA, for what the state found were unfair trade practices.

Specifically, AB’s local distributor was accused of conspiring with a catering company that was in charge of food and drink at several local concert venues to sell AB products exclusively. The case led us to dig deeper into the murky world of beer distribution (“The Imposter,” June 1). At the time, the state was starting to step up its game on regulating the beer industry, as indicated by the big fine on AB. We asked Annie McGrath, executive director of the Washington Brewers Guild, if the industry has responded by cleaning up its act. “I wish I could tell you that everything has gotten better and everyone is behaving out there, but unfortunately things are pretty much where they were when your original article came out,” McGrath says.

At the time of the article, McGrath was going around the state teaching independent brewers the intricate rules surrounding beer distribution. Following regulations is important for small brewers, McGrath says, because the rules are generally written to prevent companies with deep pockets from essentially buying business. However, McGrath says, a lot of brewers are still getting pressure from bars to provide perks in exchange for putting their beer on tap. “If only one part of the industry is hearing the education piece from a regulator, it can be pretty one-sided,” she says.

McGrath says the LCB has been stepping up enforcement on the beer front, which has stung some members of her guild. But, she says, “We asked for that.” On the bright side, the number of breweries in Washington continues to tick upward. On June 1, there were 301 breweries and brewpubs in Washington; now there are 346. As for the $151,000 fine against AB, the beer giant is fighting the case; a hearing is expected sometime next year. DANIEL PERSON

Hotel Work Gets Less Hazardous

This spring, a local union launched a citywide effort to improve working conditions for Seattle’s hotel housekeepers and room servers. The job is far more difficult than you might think; hotel workers have some of the highest rates of occupational injury of any group of workers (“Hotel Hell,” June 15).

Unite Here Local 8 created Initiative 124, designed to extend many of the protections its members enjoy to all hotel workers in Seattle, including a limit on the number of rooms housekeepers would be required to clean per shift. The initiative got the signatures it needed, and passed with 77 percent of the vote. On November 30, Mayor Ed Murray signed it into law.

Hotel workers were thrilled to “win such a huge victory and have such strong support from voters,” says Abby Lawlor, the staffer at Unite Here Local 8 who led the charge for I-124. She says that because Seattle’s Office of Labor Standards still has to develop an enforcement mechanism for the new law, it may take some time before the union can fully gauge overall changes as a result. Another reason it could take time: On December 19, a trio of hospitality industry associations filed a lawsuit against the measure.

In the meantime, the hotel workers Seattle Weekly spoke with for the story are doing well—they’ve kept their same jobs, and feel wonderfully vindicated. “We work so hard and it was great to see voters support us and show they care about hotel workers,” says housekeeper and Unite Here Local 8 member Jenny Wu. “Now it feels like we have the power. And now things will start getting better for non-union hotel workers, too.” SARA BERNARD

Future Still Hazy for MMJ

In the years after voters passed an initiative to create an “affirmative defense” for medical-marijuana patients in 1998, medical marijuana was effectively decriminalized. In 2011 state legislators went further, passing a law to create legal “collective gardens” for MMJ patients. Then came the beginning of the end. In 2012, voters legalized recreational pot, leading the legislature to recriminalize most MMJ outside the regulated, taxed recreational market. This year the medical-marijuana cottage industry effectively ended (“Pulling the Plug on Medical Marijuana,” June 29).

The sudden reduction in MMJ supply was bad news for patients, who must now choose between shopping on the black market versus paying higher prices for reduced selection at recreational stores. “A lot of patients have gone back to the old ways” in the months since MMJ phased out, says lawyer and legalization activist Jeffrey Steinborn. Patients who register in a state database can skip paying sales tax, but many have been wary of registering as users of a substance that’s still illegal under federal law.

Speaking of which, President-elect Trump chose Jeff Sessions, an alleged racist and enthusiastic drug warrior, as Attorney General. It’s not yet clear what the consequences will be for Washington’s MMJ patients. On the one hand, pot is popular: As of Election Day, more than half the states in the Union have at least partly decriminalized it. On the other hand, nothing legally prevents federal raids on Seattle’s pot patients. They could return with the flick of a pen. CASEY JAYWORK

Taxis in a Nosedive at the Airport

On October 1, the Sea-Tac Airport taxi contract officially changed hands: Instead of Yellow Cab running the airport’s taxi fleet, it became flat-rate for-hire company Eastside For Hire, now under the banner of “E-Cab.” The lead-up to that transition was mired in conflict (“Uber Alles,” September 28). That is partly due to the fact that Uber and other transportation network companies, or TNCs, were allowed to begin operating at Sea-Tac shortly after the bids for the new taxi contract came in. Sure enough, as soon as that happened, the number of TNC trips from the airport skyrocketed, while taxi trips declined.

That trend has continued, according to updated data from the Port of Seattle. TNC trips per month outpace taxis now by 20,000. And despite unprecedented growth in passenger traffic at Sea-Tac, when compared to last year’s numbers, taxi trips have continued to drop: from -16.6 percent in August, to -18.5 percent in September, to -21.8 in October.

As a result, it is harder than ever for airport taxi drivers to make a living, according to some current drivers; one driver said he made a single dollar in two hours, for instance. Salah Mohamed, a former member of the airport fleet who now drives outside the airport for Yellow Cab, and Cindi Laws, director of the Wheelchair Accessible Taxi Association of Washington, both of whom spoke to Seattle Weekly for the story in September, say that not only did drivers pay approximately $5,000 to paint their cars and join the new fleet, but they are now also paying weekly fees to a new company—E-Cab—that does not yet have its own dispatch system. That means that as airport trips for taxis go down and down, those drivers do not have a clear way to make money outside the airport. And this is crucial, drivers say: Non-airport fares through Yellow Cab made up a good quarter of their income even before Uber came to Sea-Tac.

To make matters worse, the new airport taxi fleet is significantly larger than the old one—405 cars, instead of about 240—meaning that drivers must work on rotation, giving each worker a smaller slice of the dwindling airport-taxi pie. Some drivers are now looking for a way out of the fleet entirely.

Eastside for Hire manager Samatar Guled explains that things are not looking so bad for the former Eastside drivers who are now part of the new fleet; they can still make money as flat-rate taxis through Eastside’s dispatch system. In fact, he says, those drivers are making more than before. But he concedes that for former Yellow Cab drivers, the new situation remains tough.

The Port of Seattle wrote into the new contract the stipulation that, in order to make sure drivers were making a living wage, it would conduct a driver survey every six months. Some, like Mohamed, argue that “nobody is making that,” and six months is too long to wait for a reevaluation of the contract. Guled says they’re working hard to make it better. “It’s a challenge, it’s a tough time, it’s a struggle,” he says. “We don’t have all the answers. We’re doing our best.” SARA BERNARD

news@seattleweekly.com