About six months ago, poet and arts advocate Yonnas Getahun was walking between 10th and 11th Avenues on Pine Street when he heard something he hadn’t heard on Capitol Hill before.

“For the first time I’m hearing people say racist stuff, derogatory stuff towards communities that call this place home,” he says. “I got so defensive.”

It’s something Courtney Sheehan, program director at Northwest Film Forum, was also noticing—stories from Capitol Hill residents “throwing in the towel” on the neighborhood after their friends got beat up, mugged, or harassed for being gay in one of the gayest neighborhoods in America. The two weren’t alone—The Seattle Times’ Pacific NW Magazine declared its agenda for 2015 would be to “explore how newcomers are changing our community,” a phenomenon for which Capitol Hill is ground zero.

Rather than having that same “gentrification” conversation, Getahun and Sheehan decided to do something about it: a guerrilla street project they’ve entitled Capitol Hill “Public Safety Art,” or #CapHillPSA. Starting last Friday, with the help of local postering company Polite Society, pithy messages that Getahun and Sheehan solicited from notable local artists began popping up on the telephone poles of the Pike/Pine corridor.

“We were definitely inspired by John Criscitello’s WOO girls,” Sheehan says, referencing the local artist whose guerrilla street art skewering the Hill’s new demographic has become wildly popular online: sloppy-drunk blonde “WOO!” girls wearing tiaras, bros making out with each other, fists with “BRO HOME” written around them. In that true “art imitating life imitating art” way, photos of real WOO girls stumbling drunkenly past WOO-girl posters and images of raging drunk bros going aggro next to “bro home” posters have begun to crop up online in the past couple of months. Criscitello’s contribution to the #CapHillPSA project, an image declaring that “Tech Money Kills Queer Culture Dead,” continues the theme of his series. But the most interesting thing about Sheehan and Getahun’s project is how it is illuminating the complexities of the issue.

“I hate to sound depressing, but I think the neighborhood is pretty fucked,” Christian Petersen says over the phone before laughing. A GIF artist and graphic designer who has created album covers for local hip-hop group Shabazz Palaces, Petersen has spent nine years living in the art community on Capitol Hill and watching what he calls the “totally sad David-and-Goliath story between super-rich developers and artists” unfold, and he’s had enough—he’s looking at moving to L.A. His contribution to the project, a poster bearing the message “ALL DICKHEADS FUCK OFF”—which utilizes unusual kerning that makes it difficult to read at first glance—is what he calls “a final sort of middle finger.”

“I’d like to think that somehow the neighborhood might turn around,” he tells me, “but I just think it’s too late.”

Greg Lundgren—a 20-year Capitol Hill resident, arts advocate, and owner of nearby First Hill hangouts Vito’s and The Hideout—feels the opposite. “I’m an optimist,” he tells me. “I don’t think throwing in the towel and giving up on the neighborhood is productive. I can’t do that. I think we as a community have to fight for our identity and to educate some of the new people coming in about the history of this place and where they are at. I don’t think we’ll do that successfully by telling any one group of people ‘You can’t be here, you have to go away.’ That’s so not Capitol Hill—we’ve always welcomed everyone.”

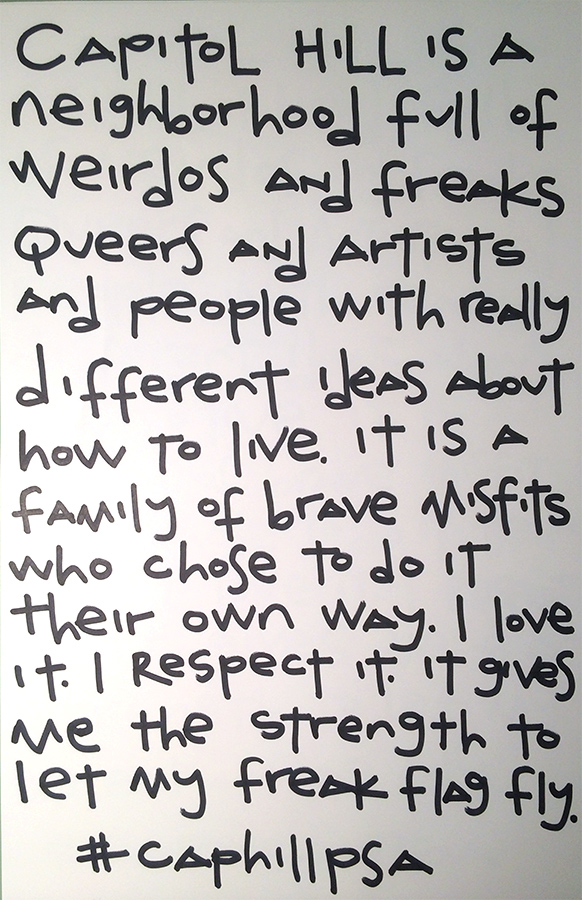

Lundgren’s contribution to #CapHillPSA reflects his nuanced approach to the conversation; rather than a pointed message or image, he wrote a small essay: “Capitol Hill is a neighborhood full of weirdos and freaks, queers and artists, and people with really different ideas about how to live. It is a family of brave misfits who choose to do it their own way. I love it. Respect it.”

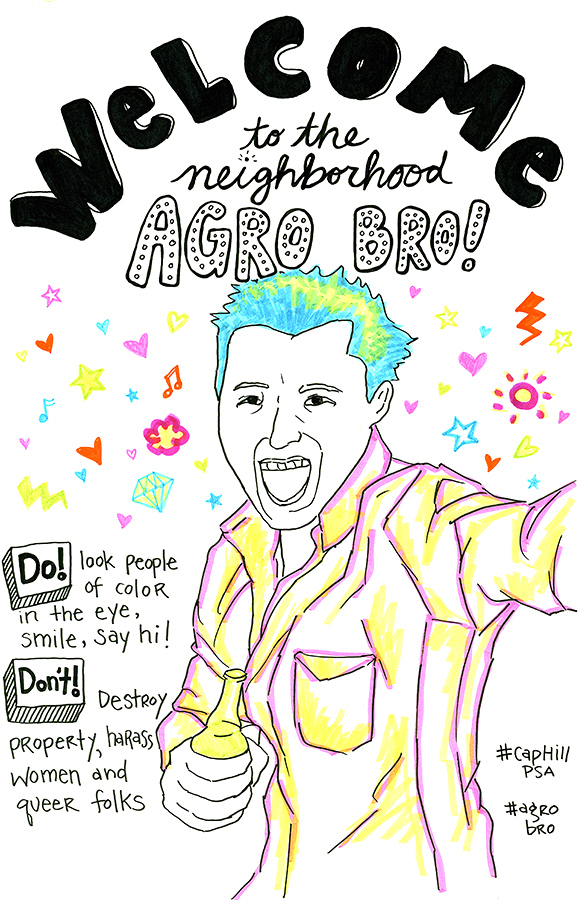

Somewhere among Petersen’s, Criscitello’s, and Lundgren’s contributions sits that of local artist Meng Yu. “WELCOME to the neighborhood AGRO BRO!” it blares, featuring a spiky-haired, beefy young man. “Do! Look people of color in the eye, smile, say hi! Don’t! Destroy property, harass women and queer folks.”

“This is a topic I’m really passionate about,” Yu tells me. “There’s so many angles to go about it. I’ve personally been a victim of several violent muggings, but I wanted to address it in a way that wasn’t purely from a place of anger. I wanted to call out the changing demographic of Capitol Hill without alienating folks. If an aggro bro walks past the poster, I want him to see it and kind of laugh at himself without feeling defensive.”

The project’s diversity of voices promises to make for a very interesting public conversation, one Sheehan hopes will “mutate” as people catch on and maybe start adding unsolicited contributions from outside the planned artist designs she and Getahun have in store for the near future.

“I think it reflects the complexity of the situation,” Sheehan says. “There’s no single coherent message.”

“Ambiguity is the word,” Getahun chimes in. “It’s exciting. These artists are telling very different sides of the conversation.” E

ksears@seattleweekly.com