Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed By Jared Diamond (Viking, $29.95)

Henderson Island is a remote dot of land in the southern Pacific Ocean. The whole island is composed of a coral-derived limestone called makatea, which easily shatters into razor-sharp shards; it rises toward the south into a jagged landscape of scarps and fissures capable of shredding the toughest hiking boots. The rock shredded the boots of Marshall Weisler, an archaeologist who spent five hours covering the five-mile crossing of Henderson from north to south. On the southern edge of the island, where the limestone cliffs drop to the sea, he found a crude shelter. Barefoot Polynesians had been there before him.

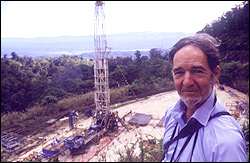

This is one of innumerable anecdotes that enrich this latest book by scientist/ science writer Jared Diamond. Unfortunately, the book needs all the enrichment it can get. Diamond’s earlier best sellers concentrated on broad but focused subjects: The Third Chimpanzee examined human nature and society in the light of the latest anthropological studies of people as apes; Guns, Germs, and Steel asked and—amazingly—plausibly answered the question: “Why did the phenomenon we call civilization develop just where it did, and why didn’t it develop elsewhere?” The Pulitzer Prize–winning 1997 Guns was not just science writing at its best; it was science in the making, science other scientists could use.

Collapse is an attempt to answer an equally large and much more urgent question: Why do some highly organized, sophisticated societies endure for millennia, while others fade away or suddenly crumble? Answering this question—and Diamond does answer it, after a fashion—requires taking an enormous number of factors into consideration, synthesizing vast amounts of historical, geographic, and statistical information.

Diamond, a fine and trenchant writer at his best, hasn’t found a natural way to structure this immense account; the chapters bump cumbersomely along, starting in contemporary Montana, then off to Easter Island and the South Pacific, back to the Anasazi of the American Southwest, south to the Maya of Yucatán, then to the freezing north for four chapters about the Vikings’ adventures in Iceland and Greenland. These 300-odd pages are salted with pockets of hugely entertaining and memorable nuggets, but getting from each one to the next is often as laboriously painful as traversing makatea barefoot. The book shows signs of hasty and slipshod editing; the author seems to have been rushed to complete it, and it lacks the extraordinary cogency and terseness of his earlier work.

The latter half of the book, dealing with contemporary cases of collapse and sustainability (Rwanda, Haiti, the Dominican Republic) and headlong development in China and Australia, is inevitably less interesting, though more topical. His final section on “practical lessons” verges on lameness. Admirers of Diamond’s earlier books will probably want to have this one as well, if only for dipping into here and there or scanning topics in the index. But they, too, will hope that the author finds a better fit between form and subject with his next effort; he’s too brilliant a miner to be wasted hauling so much slag. ROGER DOWNEY

Jared Diamond will appear at Town Hall (1119 Eighth Ave., 206-624-6600; $5), 7:30 p.m. Fri., Jan. 28.

The Children’s Blizzard By David Laskin (HarperCollins, $24.95)

Given estimates that over 200,000 people may have perished in the Indian Ocean tsunami last month, the deaths of 250 to 500 individuals during a ferocious American snowstorm way back on Jan. 12, 1888, may seem trifling. Yet with Blizzard, Seattle writer David Laskin leaves readers feeling hardly less flabbergasted by the results of that historical tempest that howled across the Dakota Territory, Nebraska, and Minnesota on what had begun as an unseasonably warm day, freezing cattle solid where they stood, burying landmarks that might have led disoriented farmers to safety, and killing children who’d only just been dismissed from their country schools.

The apathetic brutality of Mother Nature is what would endure in the memories of prairie dwellers who survived the horizontal snows and 40-below temperatures of that day. Many impecunious immigrants from Scandinavia and Germany had been lured to America’s heartland by promises of soil “so black and rich that as somebody said, you had only ‘to tickle it with a plow, and it would laugh with a beautiful harvest.'” The 1888 blizzard didn’t simply rob late-day pioneers of their families; it laid waste to the very foundations of their hope. Had the national weather-forecasting agency of that era—the U.S. Army Signal Corps, with its closest office in St. Paul, Minn.—been less mired in politics and procedures and better able to post prompt warnings of the storm, casualties might’ve been reduced. As it was, fathers died wrapping their offspring in their arms, girls and boys lost limbs to frostbite, and even some folks who lived through the meteorological disaster later succumbed, their hearts stopping as they were warmed too quickly. Laskin notes that as a result of that blizzard, coupled with subsequent droughts and financial downturns, “over 60 percent” of pioneer clans abandoned the Plains states by the late 1890s. (See the excellent 1998 Bad Land, from fellow Seattle resident Jonathan Raban, for more on the false promises sold to prairie settlers.)

Told through the awed, disbelieving eyes of storm victims as well as the Signal Corps’ beleaguered honcho in St. Paul, Blizzard recounts a poignant, heartbreaking chapter in American history. Although this book is a bit too rife with Johanns and Oles to make distinguishing its myriad players easy, Laskin (who also wrote the 1997 study of Northwest weather, Rains All the Time) draws on firsthand accounts of the snowstorm to produce an intimate, human-scale tale of climatic cataclysm that can only be termed “chilling.” J. KINGSTON PIERCE

David Laskin will appear at Third Place Books, 7 p.m. Wed., Jan. 26; at University Book Store, 7 p.m. Thurs., Jan. 27; and at Elliott Bay Book Co., 7:30 p.m. Fri., Jan. 28.

Hypocrite in a Poufy White Dress: Tales of Growing Up Groovy and Clueless By Susan Gilman (Warner, $12.95)

“When I was little, I was so girlie and ambitious, I was practically a drag queen.” So begins Susan Gilman’s tender and tantalizing memoir of her ’70s youth, an eccentric world that stretches from the sweaty streets of New York City to the glistening peaks of Switzerland. She paints herself as a girl who couldn’t avoid her individuality or desire to be a star, despite her never-ending desire to be “just like everyone else.” Perhaps stardom didn’t happen (unless you count a nudie socialist art film at age 4 or her brief stint writing for Jewish Weekly), but Gilman hasn’t done too badly here. She depicts her life’s sweetest and most terrifying moments with clarity and an unbeatable sense of humor.

With pseudo-hippie parents who force transcendental meditation on her at 10 (whose followers she refers to as “blissed-out albinos in bed sheets”), young Gilman harbors a Mick Jagger obsession until, finally meeting him at a party, he comments on her “big titties.” Yet her misadventures amount to more than another spin on Sex and the City.

The author also has her more serious, compassionate side. Sent by her paper to Poland to cover “The March of the Living,” a Holocaust memorial event, she realizes those giant oven doors were made specifically for her. Later come her parents’ divorce, a bungling new political career in D.C., and her final move to Switzerland, where she stands out as “an enormous, star-spangled, overzealous puppy.”

Gilman’s memoir finally does lose a little steam. Characters like her fiancé, “amazing Bob,” appear with little explanation (perhaps owing to severe editing). Refreshingly, she relates her unique path in terms of her own life achievements, instead of judging herself successful by virtue of the man she ultimately manages to snag. HEATHER LOGUE

Susan Gilman will appear at Third Place Books, 7 p.m. Thurs., Jan. 27.

Eleanor Rigby By Douglas Coupland (Bloomsbury, $22.95)

Souvenir of Canada By Douglas Coupland (Douglas & McIntyre, $18.95)

All that space up north—filled by a population roughly equivalent to California’s— evidently creates a spiritual yearning. Seeking to fill that void in her empty life, unmarried and childless at 36, Liz Dunn is a fat, lonely drone laboring uneventfully in a Vancouver, B.C., office until she’s moved to a moment of grace when observing the 1997 Hale-Bopp comet in the sky above a video store. As they say in the personals, Liz is spiritual, not religious, and so is Douglas Coupland’s latest novel, Eleanor Rigby.

She’s also a likable, conversational narrator in a trite, thin book almost devoid of literary style. Having created a sympathetic character, Coupland (Hey Nostradamus!, Generation X) still can’t craft a decent story. By the time, seven years later, that Liz has found and then lost some measure of happiness (besides the comet), a sudden trip to Vienna becomes just a narrative contrivance—a chance for Coupland to include observations about travel, airports, and architecture, which is his real strength as a writer. Liz, bless her, isn’t a deep thinker, nor is Coupland about what she calls “that nervous, iffy time that exists between the point at which we decide to change our lives and the point where our lives actually change.”

Much more interesting is Coupland’s A-to-Z iconographic analysis of his homeland, Souvenir of Canada, recently printed in the U.S. Freed from narrative, he basically puts captions of varying length to photos, signage, and staged tableaux from above the 49th parallel. Taxidermy, hockey, “stubbies,” Ookpiks—these foreign signifiers of what Coupland calls “a parallel-universe country” are both strange and familiar. Most of them date to a time of “relentless boosterism” spanning from Canada’s 1967 Expo to its 1976 Olympics, which also coincidentally meshes with Coupland’s youth.

It’s a period rich with invented traditions: the fostering of national unity for a nation that only got its own signature flag in 1965. Canada, in a sense, had to be marketed and branded before it could truly exist—both to outsiders and to its colonial-legacy residents. These bits of founding folklore need to be shared, no matter if they’re sold first or not. Coupland isn’t sniffing at the taint of commerce in Canada’s iconography; he’s an unabashed and happy consumer, too, but one with a sharp eye for the goods on display.

There’s also the faintest bit of narrative here, and it compares favorably to Eleanor Rigby. Photos and mentions of Coupland’s own family history bring Souvenir close to memoir—and, one hopes, farther from fiction. BRIAN MILLER

Douglas Coupland will appear at Elliott Bay Book Co., 7:30 p.m. Tues., Feb. 1. E