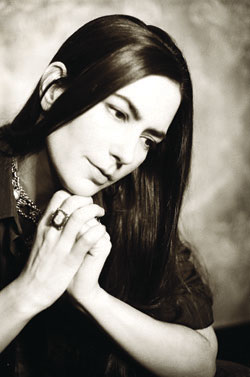

During a week’s worth of conversations surrounding the creation of her third and most adventurous release, Like, Love, Lust & the Open Halls of the Soul, Jesse Sykes and I have covered everything from her formative childhood experiences to her artistic aspirations and personal fears. However, what I really want to know about now is the necklace I’ve seen her wearing every day since we first met nearly eight years ago. You can’t find a promo photo of her where she’s not wearing it, and it’s strangely difficult to imagine what she would look like if the ornate, antiqued medallion wasn’t resting against the slope of her clavicle. “When I walk, I always go like this,” she says, her slender fingers fluttering to the turquoise stones encrusting the piece. “Because I’m always waiting for the day a stone falls out. It sounds corny, but I think that’ll be the sign from the universe that it will be time to change.”

Coming from anyone else, it would sound corny, but coming from Sykes, it’s right in character. The 39-year-old musician is prone to notions of fate, and her background as a visual artist shapes her relation to the physical world as much as it influences her earthy, intelligent approach to song composition. It makes perfect sense that she’d harbor a strong sentimental attachment to a decorative talisman.

“There’s something about the ritual,” she says. “I put this on every morning before I even wash my face, and something about it reminds me that I’m in this body and on some level empowers me.”

Empowerment is something Sykes was sorely in need of when I initially encountered her at a summer party thrown by Hattie’s Hat owner and No Depression magazine co-publisher Kyla Fairchild in 1999. At the time, she was visibly shaken from the recent disintegration of her marriage to then-bandmate Jim Sykes. The couple had been playing together in the Fairport Convention– flavored country combo Hominy, so she was not only dealing with the sorrow and disorientation of an impending divorce but mourning the loss of her musical outlet.

As, well, fate would have it, she had also just met former Whiskeytown guitarist Phil Wandscher, who was working in the kitchen at Hattie’s Hat at the time. Wandscher was nursing his own wounds, having recently relocated from Raleigh, N.C., after being shoved out of Whiskeytown by the band’s notoriously turbulent frontman, Ryan Adams. The pair’s shared emotional hangovers led first to bitter commiseration, but eventually ignited a very passionate, occasionally tempestuous romance, and ultimately resulted in the most satisfying and successful collaborative relationship of their musical careers.

The rough road to Sykes’ currently triumphant state is atypical on many levels. For one, things didn’t really begin to take off for her until her mid-30s, after many years of paying her dues on the Seattle club circuit. Even more significantly, through very careful strategic planning and smart choices, she’s managed to achieve a slow-burning level of self-sustaining success, driven purely by hard work and without the benefit of landing in any blogosphere buzz bin. She and her band, the Sweet Hereafter, have produced three albums in a little over five years, a relatively relaxed pace by today’s turn-and-burn production standards. And while hardly living the lush life, she and Wandscher have largely been able to forsake day jobs. However great her creative accomplishments have been, the most impressive development I see in both Sykes and Wandscher is a previously unthinkable level of humility and centeredness. Where they once jointly lashed out at anyone who criticized them and frequently complained about the lack of attention they were receiving, the couple have found a space where professionalism and personal responsibility have moved to the forefront.

“I now so completely understand the mechanics of how things work in this business that I don’t take things personally anymore,” affirms Sykes. “I’ve never thought of quitting, but I’ve been kicked in the chest and let it get to me. The only difference now is that the anguish only lasts 24 hours. You realize that quitting is not an option. You don’t have a choice.”

This is not to say that their quirks, both irksome and endearing, don’t still exist to a certain degree. Sykes is a disarmingly intelligent and verbose character whose reflections tend to be tangential and long-winded, regardless of the subject at hand. “Long story short” is a phrase she interjects into conversations with humorous frequency, and her fear of being misinterpreted pops out in her proclivity for editing herself (and occasionally Wandscher) midsentence. In contrast, he tends to have fewer filters, making no apologies for other musicians he doesn’t care for or philosophies he considers foolish. He also is willing to admit that he’s grown up a lot in the last couple of years, thanks to both life experience and the positive influence of Sykes.

“She’s just very sure of herself, but not full of herself,” he says, gesturing toward her as we sit in the couple’s antique-filled Fremont apartment. “And that can really affect how you relate to people when you are playing music. I kind of started falling into that trap of being a shit to the crowd. I’ve learned that that’s just not cool. Being a prick—that’s not rock ‘n’ roll, that’s just being a prick.”

It would be inaccurate to characterize Like, Love, Lust & the Open Halls of the Soul as a record just about their relationship or their personal growth as artists, but the life lessons they’ve acquired come through in the record’s mature mix of solemn, mournful balladry and unexpectedly brisk rockers. “I have nothing left to lose at this point,” says Sykes. “I realize that if I stay in my comfort zone, I’m gonna die as an artist. That [realization] was a pinnacle moment for me. The whole dynamic of this band should be change.”

The most obvious change is apparent on opening track “Eisenhower Moon,” and Sykes’ husky soprano reveals itself, sounding markedly lower and even more bewitching than it did on her first two releases, Reckless Burning and Oh My Girl. As she apprehensively queries “Is this still a good place to be/If it feels the same, how will we know/If it’s breaking down?” she echoes Marianne Faithful’s world-weary grace. “Different keys manifest different timbres, and on this record there are just a lot of different keys I’m singing in,” she explains. “Instead of trying to find the proper key, I was trying to find the right character for the song. Some are more childlike, and some are supposed to sound more like an old crone.”

Sykes has also begun to hit her stride as a guitar player. While Wandscher’s ghostly, unmistakable guitar still takes center stage most of the time, her strummings sound more in sync with her distinctive vocals. “She’s really grown as a guitar player,” says Bill Herzog, the Sweet Hereafter’s bass player. “I think she used to think of herself primarily as a songwriter and a singer, but I think over the last year she’s really worked on her own thing.”

Always an evocative lyricist, Sykes has gradually developed an exceptional ability for focusing on selective details in a scene, such as the “broken glass on a tender patch of grass” that colors the uncharacteristically upbeat song “You Might Walk Away.” “It’s sort of a pop song,” says Sykes, acknowledging the departure, “But I also wanted to look at the artifacts of teenage debauchery—I’m fascinated by remnants, like the broken bottles you see after kids have been partying in a field somewhere.”

One of the other biggest shifts during the birth of Like, Love, Lust & the Open Halls of the Soul was scrapping the mixes created by their longtime producer, Tucker Martine, and taking the record to Martin Feveyear for remixing. Both Sykes and Feveyear are extremely respectful and diplomatic when they discuss the transition, but it’s evident by their reticence to expose too many details that it was an emotionally and technically exhausting experience for everyone involved.

“I felt that the tracks were already well produced and put together, but some of the mixes felt a little flat,” concedes Feveyear. “I felt like the vocal was a little stuck on top of the mix. I was trying to be as tasteful as I could, create real space, and not get in the way of the story. I wanted it to sound like the band was right in front of you.”

Despite the architectural changes, the theme of the record remained grounded in its original inspiration. The elaborate title grew out of tattoos Sykes saw on an intriguing bar patron outside a club in Reno. “I met this extraordinary guy. He was covered in tattoos, and he had three scripted L’s tattooed on his wrist,” she reflects. “When I asked him what it meant, he said, ‘Like, Love, Lust, baby’—and he pointed at his wife and said, ‘That’s all that matter. You got that, and you got everything.’

“I could tell she was an amazing lady. Those are the kind of people that you meet once every 10 years where you never forget them. I asked him if I could name my record after that ‘LLL’ idea . . . if I could have his blessing. But when I got further into the record, I realized that one word wasn’t enough.”

One genre description isn’t enough anymore, either. Though previously locked within the confines of the gothic alt-country genre, the stylistic stretches Jesse Sykes and the Sweet Hereafter have made on this record take them into the timeless territory occupied by veterans like Neil Young. The elegant flourishes provided by vocalist Nicolai Dunger, jazz keyboardist Wayne Horvitz, and avant-garde violinist/composer Eyvind Kang broaden the palette, while Sykes’ ability to deftly weave the vulnerable threads of her thoughts into haunting-yet-hopeful lyrical observations meshes beautifully with the album’s patient tempo. “There’s an almost postmodern, glacial pacing to the writing that runs counter to the traditional components,” observes Barsuk label owner Josh Rosenfeld, who signed the band in 2003 after a recommendation from Death Cab for Cutie’s Ben Gibbard. “I think they’ve had to do a little fighting to avoid genrefication, but this record really challenges that.”

When I ask Sykes where her passion for her craft originated, she describes a moment she had at age 13, not long after her father had bought her her first guitar and obsessions with Lynyrd Skynyrd and Led Zeppelin took hold. Lying on her bed, she forecast her future. “I had this moment that was almost divine,” she recalls. “There was this voice in my head that said, ‘There’s going to be a day when you forget this passion you feel now . . . you’re going to become disconnected from it and you’re going to want to quit. You’ve got to remember this moment.’

“It sounds kind of hokey, but there are so many times I’ve had to take that vision and remember that child was right! I knew that I would die before I’d give this up.”