A year ago, Jerry Dean’s life effectively ended. He lost the mother of his children to madness and then his kids to the state. Then he left behind his job and home—just walked out—and began a kind of second life in the underworld of Seattle, beneath its highways and inside its forests.

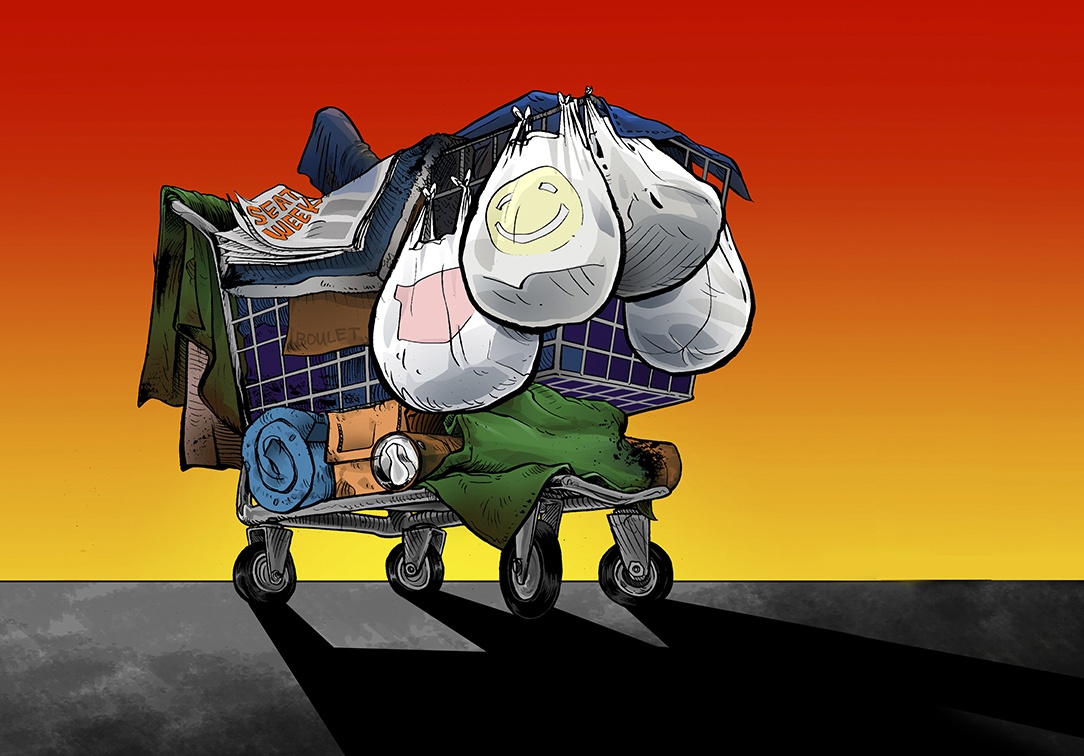

A tall, sturdy man with long dreadlocks and baggy pants, the Missouri emigrant walks and talks like steady river. Strolling among the tents of a makeshift encampment near a highway off ramp, Dean wears the eyes of a man who’s seen too much. He was Job, losing everything; now he’s Ishmael, an outcast among men, drifting from day to day in laid-back, drug-numbed agony.

“I get high and spend most of my time helping other campers,” he says. “Collecting wood, water, helping with other tents. I do a lot of cooking for people. . . . That makes me feel good, even though it’s a mask—a cover-up for how I really feel, deep inside.”

The end for Dean began while living in the Nickelsville homeless encampment last fall, he says. After his children’s mother accidentally hit one of the kids while trying to hit Dean, he called 911. That brought Child Protective Services into the picture. The mother lost custody, and CPS told Dean to sever ties with her for the good of the children. He couldn’t, so he eventually lost custody, too. After a few weeks of one-hour visits with the kids that always ended in tears, he couldn’t take it anymore. The pain was too much. So he dropped out.

“I left my place,” says Dean. “I just abandoned everything. I stopped going to work. I never went back home.” He found himself camping in a place called the Jungle alongside hundreds of other refuge-seekers.

Dean wasn’t alone. Homelessness has been on the rise nationally for decades. It increased by 19 percent last year in King County, according to the most recent One Night Count. At the end of 2015—the final year of Seattle and King County’s Ten Year Plan to End Homelessness—nearly 3,000 people still slept outside within Seattle city limits. Frustration with the system breakdown seems to be growing everywhere, particularly among home and business owners upset about the effects of visible poverty on their communities.

About a month after Dean walked into the Jungle, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray and King County Executive Dow Constantine declared a state of emergency with regard to homelessness. Made on November 2, 2015, it was an unprecedented use of a power typically invoked during natural disasters or civil unrest. The declaration included a formal request for emergency assistance from the state and federal governments—and for them to start adequately funding housing and social services. It also added some moderate, one-time-only funding to the homelessness budget, taken primarily from the sale of an unused city property. Yet the “emergency” remained largely symbolic until January 26.

It was on that evening that Murray delivered a televised address to the city defending his handling of the homeless crisis and urging unity. The speech was apparently aimed at two competing constituencies: home and business owners and social justice advocates. “I hear your frustrations, and I share them,” Murray said. “Ending homelessness will be as difficult as any challenge we face as a city. I believe Seattle can do this, by listening to each other, challenging each other, collaborating with each other, and above all by respecting those who are suffering.”

Just as that speech ended, the news broke: Five people had just been shot in the Jungle.

“More than 45 people have died on the streets of Seattle this year, and more than 3,000 children in Seattle Public Schools are homeless,” Mayor Ed Murray told the cameras just hours after signing the declaration. He revealed that the city would allocate an extra $5.3 million to the crisis; the City Council eventually raised that by another $2.3 million by tapping into real-estate tax money. Overall annual Seattle homeless spending would increase from $40.8 million in 2014 to $50 million in 2016. Since the declaration, both the state and the feds have also increased homelessness-related funding slightly.

It has not been enough. Even just providing enough emergency shelter for all Seattle’s homeless would require doubling the homeless budget to about $100 million per year, according to the mayor’s office. And that doesn’t include any of the mental-health, addiction-recovery, or housing services leaders agree are needed to truly solve homelessness, rather than just manage it.

Before it was an emergency, homelessness was a problem. In 2014, his first year in office, Murray convened a task force in search of a solution to what had become impossible to ignore. It called for city-sponsored encampments, and in 2015 the Council and Murray passed a bill authorizing three such encampments of up to 100 people each in Interbay, Ballard and Rainier Valley. But once they began opening in November 2015, the encampments were not welcomed by all—particularly some nearby business and home owners.

Those critics did not disappear once Seattle shifted to emergency status. At a homelessness symposium at Seattle University in December, one month after he’d declared the state of emergency, Murray decried neighbors who “denigrated and demonized homeless people. Discussions in our neighborhoods that said, basically, ‘You need to do more process.’ I did a year’s worth of process, and over 40 people are dead.”

At the same time he was espousing this humane rhetoric, Murray’s administration was evicting unauthorized homeless encampments over the objections of advocates. Eviction crews regularly violated what meager rules protected homeless campers from surprise sweeps or the loss of valuable property—something Murray and his staff wouldn’t acknowledge for several more months. Outreach accompanied the evictions, funded in part by emergency funds. Dean says that during that winter, city-contracted workers clomped up the muddy hills of The Jungle to offer trash bags, shelter beds, motel vouchers, storage, and assistance moving. “I utilized Pete’s Place at that time,” Dean says, referring to a homeless shelter, “and I got into the program through one of the REACH outreach workers” from Evergreen Treatment Services.

Then came that fateful night in January when three teenage brothers shot and killed two people and wounded three more at a campsite under I-5. At an impromptu press conference by the site of the shooting—held just after he finished his televised address—Murray promised that the entire underside of I-5 between Dearborn and South Lucille Streets would be assessed by fire chief Harold Scoggins. Scoggins’ report was published three weeks later and painted the area as a kind of cross between Dante’s Inferno and the swamp in Labyrinth. “The area has no lighting and can be especially hazardous because of the steep slopes, accumulation of solid and human waste, burn pits, and mudslides,” it said.

Murray responded to the murders by escalating encampment evictions. While the city cleared 35 camps in January, that number increased to 54 the month after the killings and kept rising throughout the next two months. He also vowed to clear the entire Jungle of campers. That threat of eventual eviction itself did much of the work, persuading the vast majority of campers to leave before Seattle police and outreach workers formally cleared the underside of I-5 at the beginning of last month. During the clearance, police shot and killed a man they say was attacking another person with a knife.

Seattle hasn’t lacked for critics of the way it handles homelessness, particularly among home and business owners. For instance, at a meeting in Ballard about a local encampment two months before Murray declared emergency, attendees “grumbled, others made angry speeches, and some screamed at the Murray administration officials,” according to The Seattle Times. Five months later, that well of frustration gave rise to the Neighborhood Safety Alliance, which advocates for what its members describe as a “tough-love” approach to homelessness. In practice, co-founder Cindy Pierce told Seattle Weekly in March, that means the city should either forcibly detain or banish homeless people who don’t voluntarily surrender to proffered shelter and services. “They need to have shelter,” she said. “They need it. I think we should force them to do it, because what they’re doing is illegal out in the streets. If they don’t want to do it, we don’t have a place for them in the city.”

The NSA isn’t alone in its antipathy toward encampments. Two months before declaring emergency, Murray hired former U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness director Barbara Poppe to analyze and make recommendations about Seattle’s homeless response system. While at USICH, Poppe had publicly opposed then-Mayor Mike McGinn’s attempts to establish a city-sponsored encampment. This past February, as Murray’s consultant, she doubled down, calling them “unconscionable,” according to The Seattle Times, though her report wouldn’t come out until September (more on that later).

Yet there’s also been political pressure in favor of tolerating encampments. In May, after Murray announced a plan to sweep The Jungle in two weeks, Councilmembers Sally Bagshaw and Mike O’Brien pushed back. Their cause was bolstered by the state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which threatened to sue if Seattle cleared the Jungle without offering adequate housing or shelter first. Murray backed off, postponing the eviction indefinitely.

In August, the state ACLU and Columbia Legal Services took the offensive when they published a draft bill that would tighten rules on encampment evictions—essentially allowing the city to evict campers only if there is somewhere else for them to go. “If our larger goal is to transition unsheltered people and families into permanent housing,” said O’Brien, the bill’s sponsor, on his blog, “then continually displacing them, destabilizing their lives, and compromising relationships and connections to services is not producing the results we need.”

But this time Bagshaw took the mayor’s side, trying to keep O’Brien’s bill from even being introduced for consideration. When she failed, Bagshaw worked for weeks alongside O’Brien and stakeholders, including the mayor’s office, to eventually produce a largely gutted bill that took an extremely liberal view of what counts as adequate shelter for the city to offer before an eviction can proceed. At the same time, O’Brien produced his own refined bill, tailored to meet the needs of constituents he’d heard from. It wasn’t as strong as the original bill proposed by advocates—allowing, for instance, that “if an outdoor living space is in an unsafe or unsuitable location, the City may undertake immediate removal action.” Both bills are currently on hold until the end of budget season in late November.

Seattle now spends more on homelessness than at any other time in its modern history. According to the mayor’s office, the city provides nearly 2,000 shelter beds per night—a 20 percent increase from last year—and has put more homeless people into housing than any city save New York and L.A. We also opened a supervised car-camper parking lot (which closed after turning out to be prohibitively expensive) and unsupervised “safe zones” for car campers. Last year, city workers began searching for sick homeless people in a mobile medical van.

To their credit, no one in City Hall believes that this is adequate. There’s less agreement, however, on what further fixes are needed.

At the beginning of September, Poppe turned in her report on how to fix Seattle’s homelessness-response system. The most urgent failure she found was a bottleneck of long-term guests at emergency homeless shelters whose removal, she reported, would allow shelters to gradually pump the entire homeless population into housing. Between this and better management practices, including competitive bidding for city contracts, Poppe claimed Seattle could end all homelessness in five years.

Homeless advocates criticized the reports for glossing over the question of how to keep homeless people alive in the interim, before managerial improvements would be able to completely revolutionize our homeless-services system. They also made much of a caveat at the beginning of Poppe’s report which acknowledges that the root issues behind homlessness—including low wages, expensive college, a broken social infrastructure, and racism—are “beyond the scope of this analysis.”

These staggering issues are indeed the systemic roots from which homelessness flowers, and they exist beyond the reach of Seattle’s municipal policy Rototiller. This raises the disturbing possibility that the truth is too unpopular for our leaders to speak: Homelessness is insoluble, at least by our hands—a problem that we can manage but never resolve.

Be that as it may, the consensus inside City Hall is that dealing with homelessness in the long run means addressing housing affordability and accessibility more generally. To do so, Murray convened a task force in 2014 to make recommendations comprising a “Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda.” In broad strokes, the 59 HALA recommendations boil down to a “grand bargain,” in Murray’s words: Developers will promise to keep some rents relatively cheap, and in exchange the city will allow them to build bigger and denser and also throw in some tax breaks. The goal is to increase the supply of both publicly subsidized and privately marketed housing. In August, city voters approved one of HALA’s most important individual recommendations, doubling the multi-year housing levy from $145 million to $290 million. The mayor and Council have already legislated some of the other recommendations, including a tax break for developers who build guaranteed low-income units and an anti-discrimination ordinance.

While bad things happen to people in every neighborhood and income bracket, it’s fair to say that living outside kills dozens of people in King County each year. As of August, the count for this year was 58 dead. The average age at death was 49. The causes were overwhelmingly preventable or treatable, including drug overdose, pneumonia, blunt force trauma, hypothermia, gunshot wounds, and septic shock. The youngest casualty was 24.

Since the mayor declared a state of civil emergency, Seattle has evicted more than 587 homeless encampments, meaning that likely hundreds or thousands of Seattleites have been swept in the past year. According to an analysis of data provided by the Human Services Department, the sweeps have been mostly clustered around downtown, with tentacles spreading to SoDo, Capitol Hill, South Lake Union, and Eastlake. A smaller cluster exists around Ballard. Here’s a time lapse map of the evictions:

Perhaps 500 people lived in the Jungle at the beginning of this year; by August, with the majority of the Jungle’s residents evacuated, city workers had moved just 27 into housing, mostly via drug-recovery programs.

Dean was not one of them. He’s not ready to go in. “I’ve got friends at different camps,” he says. “I like to move around. Switch my scene up.” But for the past two months or so, he’s lived in an encampment that is unsanctioned, but—for the time being, at least—tolerated by the city. It is called, accurately, the Field: a humble patch of grass and mud on the perimeter of the soaring, serpentine intersection of I-5 and I-90. This is one of the places campers went after fleeing the Jungle, which was nestled in the highway’s underbelly. It is a concentrated camp, brimming with tents, divided into a handful of neighborhoods delineated by carefully arranged tents that sometimes form protective cul de sacs. “Some of us closed off our area, made it so you have no business walking past our tents unless you live in our little circle,” says Dean.

Pros: There are porta-potties, dumpsters, and lots of food and water donations. Also, police and fire can supposedly respond to emergencies in a couple of minutes, while responding to encampments beneath I-5 could take much longer because the service roads are bad. According to Seattle police, this helped save the life of a woman who was shot in the stomach in July. Cons: About a hundred people, many mentally ill and/or struggling with dysfunctional substance use, are now jammed together into a tight space. Also, there’s no roof. Dean and his cohort now camp beneath the open, pissing sky.

The night before we meet at McDonald’s for our final interview, a smoking buddy of Dean’s was shot in the neck in the street in front of the Field. The victim lived, but still, it shook Dean up. Also, his phone got stolen, again.

Dean says he wants out. He’ll find a way: sober up, find work, go to anger-management classes, and someday get his kids back. “I don’t want to be a single father facing my babies while their mom’s running around here losing her mind,” he says. But at the same time, “I’ve got to build my strength up so that I can just turn my back on her, forget about her. For the kids.”

We wrap up the interview. Dean stops by the condiment stand to get salt to gargle for his sore throat. He’s sick, he says, and has had a lot of back pain and depression over the past few days. We walk out between the swinging glass-and-metal doors, shake hands, part. As I’m unlocking my ride, relieved to finally go home and kick back on the couch after a long day at work, I turn around and watch Dean walking away. Framed by the erupting on- and off-ramps of the I-5/I-90 intersection, his figure recedes toward the sea of tents and mud in the yellow evening twilight.

cjaywork@seattleweekly.com