INITIALLY, WHEN MY boyfriend asked me to celebrate this Christmas, our first together, with his brother’s family in Lake Oswego, Ore., I was reluctant. I did not relish the prospect of spending my holiday sitting quietly, hands folded in my lap, playing the role of the mysterious “friend,” while his 8- and 11-year-old nieces opened presents.

But after repeated assurances that this would not be the case, I consented. As it turned out, the visit was swell. His brother is an excellent chef, and his sister-in-law graciously had a bottle of Knob Creek waiting when we arrived. And their daughters didn’t seem the least bit flustered that their uncle was snuggling with another man on the sofa.

My beau was right: I didn’t have to change a single thing about who I was or how I behaved. Except one. As soon as I set up my laptop in their home office, I switched my desktop wallpaper. Sophisticated or not, I didn’t feel it was right to introduce two prepubescent lasses to Betty Davis.

“What’s wrong with Bette Davis?” you ask. Surely the girls have figured out that most fags can’t complete three sentences without quoting All About Eve. But I said Betty—not Bette—Davis. And believe me, there is a big difference.

Before there was Betty Davis, there was Betty Mabry, from Homestead, Penn. As John Szwed notes in So What: The Life of Miles Davis, Betty was “everywhere in New York in a way that was possible only in the late 1960s.” She was co-owner of a club for teenagers, appeared on TV game shows, and modeled for Ebony, Glamour, and Jet. In 1967, she made her first foray into pop music, writing “Uptown” for the Chamber Brothers’ The Time Has Come album.

In early 1968, Betty became involved with recently divorced jazz giant Miles Davis, and the two soon married. Betty, who was tight with black rockers like Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone, turned the trumpet player on to a new musical world. At first, her influence on Miles was reflected in subtle ways: She graced the jacket of his Filles de Kilimanjaro, and he penned the track, “Mademoiselle Mabry,” in her honor. Miles divorced Betty within a year (in his autobiography, he cited her conduct as “too young and wild”; he also alleged she slept with Hendrix), but his next album, the groundbreaking fusion outing Bitches Brew, clearly bore the stamp of her tastes.

Miles had already produced a demo single for Betty for Columbia Records, featuring members of Hendrix’s band, but a proposed album never materialized. In 1973, Betty dropped her self-titled debut, eight cuts of rough, uncompromising funk featuring Santana and Sly Stone sidemen and the Pointer Sisters. With ditties including “If I’m in Luck I Might Get Picked Up” and “Anti Love Song,” Davis took female sexual liberation to extremes that would go unequaled until Millie Jackson arrived years later, while her husky, soul-shouter come-ons made Tina Turner sound like an opera diva. Though her two subsequent albums, 1974’s They Say I’m Different and 1975’s Nasty Gal, showed little aesthetic evolution, they were just as unrelenting in execution.

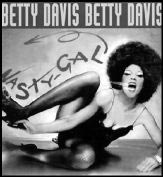

A former fashion design student, Davis—who always sported a monstrous afro—was just as extreme in her visual presentation, setting an outr頳tandard later reflected in the looks favored by Nona Hendryx and Grace Jones. On the cover of Betty Davis, she poses in denim hot pants and a pair of silver leather thigh-high platforms that surely didn’t escape the notice of LaBelle’s stylist. They Say I’m Different finds her sporting a Zulu-warrior-meets-Aladdin-Sane one-piece ensemble plus marabou-trimmed blue boots. Nasty Gal is graced with a shot of Betty in a simple black teddy, fishnets, and stiletto heels, legs spread in a provocative position that makes the cover of Vanity 6 seem modest—that’s the picture I deleted from my desktop as soon as we decamped at Lake Oswego.

Sadly, Betty’s musical career met with little success, and by the decade’s end she had vanished from the public eye. Today, her whereabouts remain unknown. Despite the usual rumors (i.e., death by drug overdose, etc.), she is presumed to be living a quiet life somewhere in Pennsylvania.

My boyfriend has proposed an alternate theory—that Betty Davis was so funky and out of this world, she began to vibrate at a different frequency and became invisible on our ordinary plane of existence. She’s still out there: We just can’t see or hear her. Fortunately, the British imprint MPC Ltd. has just reissued her three albums on CD and vinyl. So maybe, just maybe, if we play them often and loud enough, she’ll come out of retirement. After seeing how accepting they are of their big gay uncle, I reckon by next Christmas my boyfriend’s nieces will be ready for her.