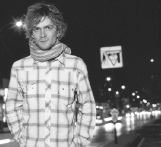

BRENDAN BENSON AND THE WELL-FED BOYS, THE WHITE STRIPES

Moore Theatre, 682-1414, $16 adv. 8 p.m. Sat., June 8

IT SOUNDS LIKE an apocryphal tale, but the way they tell it, Brendan Benson was born a pop progeny.

Back in early-’70s Detroit, Benson’s parents—a hip young couple with a fittingly cool record collection—would set Brendan’s playpen between the speakers of their stereo. Barely out of diapers, young Brendan would groove furiously to his folks’ vinyl, baptized by the sounds of the Beatles, Bowie, and the Stones. Even at that unusually early age, it seemed the boy was destined to become a rock ‘n’ roller.

You might dismiss the anecdote as nothing more than bit of well-calculated mythmaking, something an imaginative publicist conceived to jazz up the old artist bio. You might, if it weren’t for the fact that Benson’s two albums, 1996’s Mississippi One—doggedly referenced as one of the forgotten masterpieces of the past decade—and this year’s much belated follow-up, Lapalco, were among the best slabs of pop confectionery in recent memory.

Outstripping its predecessor, Lapalco achieves a tricky balance, merging melancholy meditations with gleeful bubblegum fuzz. It’s the work of an instinctively gifted auteur, the kind of glorious noise that makes you think the stories surrounding baby Brendan might just be true.

“WHY DID I sign that?”

Brendan Benson is talking to a U-Haul agent in Tucson, Ariz., negotiating the paperwork to rent a van that will take him and his band, the Well-Fed Boys, up the West Coast on a tour opening for the White Stripes.

“Um . . . why did I sign that?”

For Benson, it’s likely a familiar question. In 1996, not long after inking a deal with Virgin Records—on the strength of some homemade demos he’d recorded with friend and Jellyfish leader Jason Falkner—Benson would be cursing his decision to sign with the company.

Within months, Virgin had rejected Benson’s Falkner-produced full-length debut, forcing him to recut the album with Ethan Johns (Rufus Wainwright, Ryan Adams) behind the board.

The resulting disc, Mississippi One, sold modestly but earned lavish, uniform praise from critics and musicians alike—everyone, it seemed, except the Virgin brass. After funding, then rejecting, Benson’s demos for a second record, the label dropped him.

“They promised me a lot of things, led me to believe a lot of things that never came true,” he says. “And, of course, I had high hopes and let myself believe it.”

Benson knows his experience is not unique, that you could substitute his name for a hundred other gifted woulda-been, shoulda-been songsmiths.

Still, it would be another six years before Benson—disappearing almost completely from the rock radar—would release another album.

This wilderness period found Benson relocating from Southern California, where he’d spent the ’90s, back to his native Detroit. Despite the change of scenery, Benson found that his confidence and creative instincts had been badly shaken by the disappointing Virgin episode.

“I was very, very discouraged and depressed,” he remembers. “After the first record, that whole experience, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do anymore. I didn’t really care or want to make any decisions about music. I finally moved back to Detroit, got a house, and built a little studio in there.”

Eventually, Benson’s malaise passed. He set to work alone, writing and recording new songs and playing all the instruments himself. “After a while,” he says, “it occurred to me that I had a record.”

Last year, he sent an unsolicited copy of what would become Lapalco to Startime International Records, a small, well-respected New York City label run by Isaac Green. When Green got Benson’s package, there was no information save for a short handwritten note: “This record needs a home.”

Green agreed to release the record (featuring several salvaged collaborations with Falkner), and this past February, the world—or at least the small pocket of pop fans who hadn’t forgotten him—finally had Brendan Benson back.

The protracted absence hasn’t diminished Benson’s way with a hook or the luster of his fragile tenor. In fact, Benson’s latest is the kind of disc that will occupy a physical and spiritual space between your Badfinger and Big Star albums. Neither a pale imitation nor the predictable paint-by-numbers rendering of so many pop revivalists, the album illustrates the crucial difference between regurgitating your influences and actually digesting them.

Even when he brazenly lifts from others—the Cars keyboards of “You’re Quiet,” the Mamas & the Papas chorals of “Metarie”—Benson weaves those snatches of sound into his own scheme with such elegant aplomb you almost forget the source.

Myriad Me-Decade influences (Nilsson, Raspberries, Todd Rundgren) carry the album along, but the record seems most under the sway of the home studio, one-man band aesthetic of Paul McCartney’s early solo sides.

“I love those records like Ram and McCartney,” says Benson, who often covers Macca’s “Let Me Roll It” in concert. “But,” he adds pointedly, “Lennon is my favorite Beatle.”

He wryly references the “clever one” on “Folksinger” (“my girl . . . ain’t got time for my bed-in/She said stop pretendin’, you’re not John Lennon”) while appropriating George Harrison’s teardrop slide for the intro to “Eventually.” In fact, the ghost of the Fabs haunts much of the album, notably on the mesmeric piano stomp (“Jetlag”) that closes the disc.

“Ahh man, the fucking Beatles,” mutters Benson. “People said that about [Mississippi One] a lot too.” Understandably so, since Benson chose to open his debut with an Abbey Road-style medley. “It’s really flattering, but I just don’t agree. I mean, it’s an impossible thing to live up to.”

Handpicked by his friend and current rock “it” boy Jack White to open dates for the White Stripes in America and the U.K., Benson and his band are set to return to Europe immediately after their upcoming Seattle date. Admittedly, Benson is a reluctant road dog, preferring the familiar comforts of his own grown-up playpen, the home studio. “Yeah,” he chuckles, “I like to be alone and be at home a lot, just working in the studio. I love recording music more than I do playing live.”

Fair enough. And as long as it means Benson’s going to be putting out albums like Lapalco a little more frequently, no one’s going to mind.