The last thing one wants from political drama is zealotry and easy targets, and David Hare’s play Stuff Happens—a nuts-and-bolts, backroom examination of Bush’s inner circle during the lead-up to the Iraq war—goes out of its way to be, if not exactly objective, at least comprehensive and inclusive and fair-minded. And that, in short, is the problem. As directed by Victor Pappas, this claustrophobic epic of neocon realpolitik and the selling of war is as linear and canny as a PBS documentary. The performances run from adequate to superb, the pacing is tight and tense, and the play is admirably ambitious in scope. Stuff Happens, which clocks in at over two and a half hours, is never dull—nor is it all that intriguing or enlightening or shocking.

Despite its fictional access into the secret war-room negotiations and eleventh-hour maneuvering by the real-life players in this all-too-serious moment in history, the play offers little more than an educated-person’s move-by-move recap of the rush to war—the WMD balderdash, Tony Blair’s “dossier,” President Bush’s “Axis of Evil” speech, the doctrine of the pre-emptive strike, Colin Powell’s dissent, the sabotaging of Hans Blix. Rather than portraying the Shakespearean sweep of historical drama—with its perfidious schemers, loyal retainers, ambitious climbers, and inscrutable leaders—Hare’s play comes across as a dramatized history lesson, remedial and unspectacular and more concerned with capturing the timeline than the times.

Stuff Happens opens on a promising note, as key players in the coming drama—Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz, George Tenet, etc.—are introduced in a rapid-fire prologue, narrated network-news style (“In locker-room terms, Don [Rumsfeld] is a towel snapper”). The device effectively creates the sense that something genuinely monumental is about to go down; it also sets the tone for the play, with its documentary-style reportage and ticking-clock atmosphere. From here, we jump to a January 2001 meeting of the National Security Council, during which CIA director Tenet shows Bush, Powell, and crew a satellite photo of an Iraqi factory, claiming that it could be a producer of WMDs. This scene, with its who’s-on-first linguistic go-around about the photograph, is genuinely funny, and it’s too bad the play doesn’t contain more such Strangelove-like moments of absurdity.

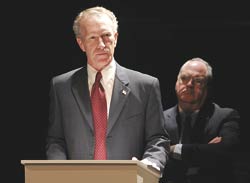

The president himself (well-played by R. Hamilton Wright) is portrayed with restraint, not as a tongue-tied idiot or Machiavellian savant, but, rather, as a sort of Tourettic, scowling cowboy with a serious case of echolalia. Bush is hardly seen as central to the unfolding of events—he’s just another player in the large ensemble. The problem with this is that Stuff Happens, which strives for the large-scale and complicated grandeur of a classic history play, practically screams for a strong, charismatic lead—someone to anchor the twists and turns of the political machinations.

Nor is any other character granted enough of a spotlight to really carry the show. Charles Dumas is good as the embattled and besieged Gen. Powell, the military man who barely manages to offer moral and ethical counterpoints to Bush’s monomaniacal pack of hawks. In portraying Powell’s protracted struggles to do the right thing, Dumas comes closest to providing the play with the kind of psychological depth it needs. Also strong are Frank Corrado as Rumsfeld, Mark Jenkins as Blix (he also plays British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw), and Mark Chamberlin as Blair. In fact, if Stuff Happens has anything even remotely new or interesting to reveal to the average reader of daily newspapers, it is in the telling of Blair’s involvement in the international push for war. Neither a complete dupe nor an all-fronts liar, Blair is on the outside looking in; his position somewhat mirrors that of the American public.

In the end, Hare’s play suffers most from a lack of imagination. As a historical document, Stuff Happens can be valued for its straightforward recitation of the events, and for the clear-eyed, wonkish way it links those complicated events in a chain of cause and effect leading up to the current tragedy in Iraq. As a work of fiction, however, it is kaput. It has neither the sharpness of satire nor the exaggerated claims of political melodrama, either of which might have shaken up the familiar elements to create something fresh or surprising, something with a different perspective. All the stuff that happens in Stuff Happens happens to be stuff we already know. Simply to see it dramatized, with such fealty to realism, isn’t enough.