You’d be hard-pressed to meet a Seattleite without some kind of opinion on Paul Allen. The Microsoft-co-founding billionaire has had more influence on this city than just about anyone else over the past two decades. And his latest endeavor has the city’s musicians in a crisis of conscience. The idea: the Upstream Music Festival and Summit, which will take place next May 11–13 in a variety of venues in Pioneer Square and SODO.

Upstream will be a mix of industry panels and musical performances aiming to bring musicians together with some of the city’s other artistic industries—tech, film, and video games—while shining a light on the area’s emerging musical talent. The festival is dedicated to booking 75 percent local acts, and paying all of them.

Jeff Vetting, Upstream’s executive director, said the idea for the event was borne of Allen’s love of music, which Allen hasn’t been shy about sharing with Seattle. He built the Experience Music Project in 2000, itself hotly debated at its launch. “Paul’s work for the arts for the city of Seattle has been amazing,” says Vetting. “He’s a guitar player [in his band Paul Allen and the Underthinkers], a really big fan of seeing live music. And so he wanted to know—how could we support emerging artists?”

But some local artists have trepidations about the festival. Pete Capponi, who plays drums in Seattle band Steal Shit Do Drugs and organizes the annual punk festival Pizza Fest, says his first reaction to hearing about Upstream was mixed. “Paul Allen is one of the richest men in the world. To have a person like that say, ‘I’m going to help out the little guy,’ it’s a little tough to believe.” But Capponi also made it clear he was open-minded about the idea. As a longtime Seattle resident, he has enjoyed festivals like Bumbershoot and the Capitol Hill Block Party, but in recent years both have evolved into events he no longer enjoys. “You’re basically spending most of your time waiting in lines or navigating crowd situations.”

A rendering of Upstream’s stadium-side mainstage. Courtesy of Upstream

Upstream will feature 300 performances from 200 bands as well as a two-day summit of panels, workshops, meet-ups, and cocktail hours, which will take place in the WaMu Theater. “We’re really hoping to capture that sort of lobby con that you see when you go to a conference, where everybody’s hanging out in the hotel bar,” says Vetting. “We’d like to create that in WaMu Theater.” The summit also hopes to include an innovations showcase dedicated to music apps and websites, as well as a new-music-gear expo a la the annual National Association of Music Merchants Show in Anaheim.

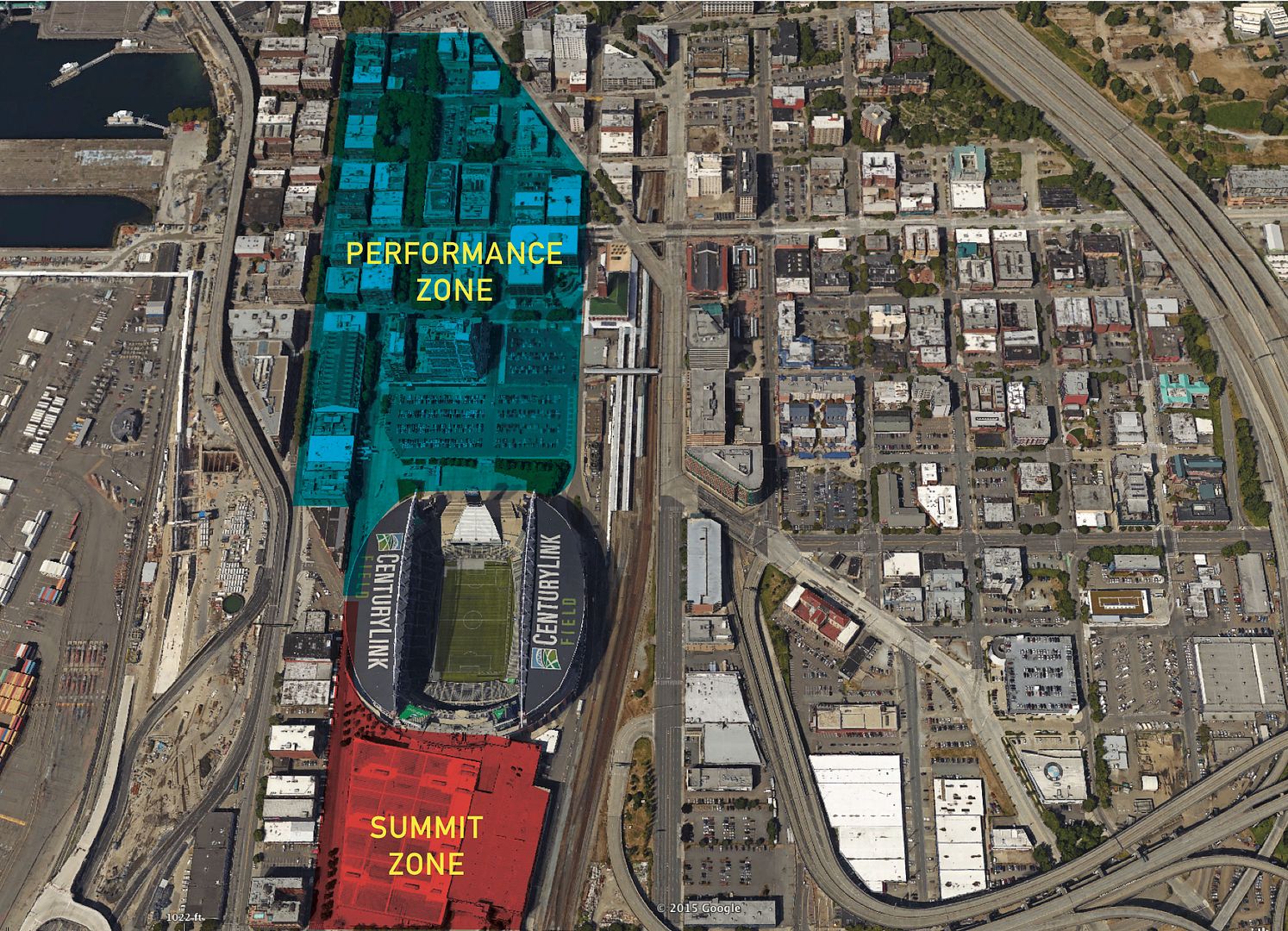

The festival’s main music stage will be in the plaza area north of CenturyLink Field, utilizing the stairs outside the stadium in front of the Hawk’s Nest. The stadium’s north lot will be transformed into a gathering spot for food trucks, sponsorship tents, and more, which will be accessible to the public as well as festivalgoers. Also open to the public will be a series of concerts in Occidental Square, which will be broadcast on KEXP. Additional music events will take place throughout Pioneer Square, both at existing venues like Central Saloon and at art galleries, coffee shops, restaurants, underground spaces, alleys, and rooftops. “All of the great geography that is Pioneer Square,” Vetting says, “we plan to incorporate into musical performances. We’re really working on this concept that we like to call ‘Surprise and Delight,’ where we have music everywhere, with different shows that come up at the last minute, or marching bands, or buskers, or everything music around all the time.”

One of Upstream’s goals is to position itself as an artist-friendly festival. Vetting says he wants to ensure that all artists get treated like headliners no matter what level they are—making sure each act has a green room, a good load-in time, and a chance to sound-check. “We want to make sure that every band that plays gets a decent wage per performance. We really want to put the focus on the artists.”

Michaud Savage, a classical guitarist who runs the nonprofit Seattle Composers Alliance, hopes those aspirations come to pass. Savage says he earns nearly the same wage that his grandfather did as a working musician in Seattle in the 1970s and ’80s. “I want to believe that it would be a good-paying gig,” he says. “Especially for festivals, you tend to get fucked.” Savage is also hopeful that the summit will be an educational resource for the city’s working musicians like him who are struggling to adjust to music’s ever-morphing business models.

To that end, Vetting says the festival will offer deep discounts on admission for local artists, even if they aren’t booked to appear. “I think that being musician-friendly goes beyond the work of being friendly to the artists playing your fest. I think you need to be musician-friendly to everyone.” Vetting also says the Upstream ticket price will be lower than those of other local festivals.

Upstream is hoping to draw some 40,000 attendees in its first year, which seems ambitious on the backs of mostly regional acts. But Vetting says they have lots of ideas, like having events curated by celebrities, record-label showcases, and even allowing other festivals to program events. “The thing that we really want to do is drive people to see these kinds of emerging artists, these new bands.”

“What would make me a fan of it,” says Capponi, “is to really include the vastness of the Seattle music community, and also be very mindful of the vibe of the actual shows. If they throw up something at the Central, really listen to Michael Gill, who’s the booker of that place, because he’s made it a success. And understand why it’s been a success.” Capponi says that anything that helps make Seattle a place musicians can thrive is vital to the scene, especially as more and more artists are priced out of the city by escalating rents. And if Upstream can help that, than he sees it as a good thing.

Kate Becker, Director of Seattle’s Film & Music Office, agrees. “I do believe that Upstream is creating something that does not exist now in our festival landscape. The focus on our local music ecosystem offers tremendous opportunity for our creative economy.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever come across someone in Seattle who said, ‘We need less live music here,’ ” says Vetting. But he also knows the festival is about more than just music—it’s about community, and not just among musicians. Vetting has been working with local residence councils, businesses, and the Pioneer Square Alliance to ensure that the neighborhood’s concerns are being addressed, whether by picking up the trash generated by the festival or making sure not to displace the area’s homeless population. Pioneer Square is a historically and culturally rich part of the city’s history, and Upstream hopes to add to that. Speaking of the neighborhood’s shotgun-wedding chapel on First Avenue, Vetting says “Nothing would make me happier than if we had the most weddings at a festival.” Upstream will announce its full lineup early next year, with ticket sales starting in the fall.

music@seattleweekly.com