If you’re in jail in the state of Washington, and you haven’t been convicted of a felony crime, you have the right to vote.

But a report released recently by the advocacy group Disability Rights Washington found that of the state’s 38 county jails, “a vast majority … fail to facilitate the right to vote” and “only a handful” have formal voter-access policies in place. Even at jails with formal policies, the track record isn’t fabulous; when DRW researchers “asked staff and administrators about the policies, many did not know about the polices or did not actually use them.”

DRW is particularly interested in this issue because according to a study by the federal Bureau of Justice, U.S. jail inmates are four times more likely to have a disability than the general population. Perhaps not surprisingly, an even smaller fraction of the state’s jails provide specific voter accommodations for people with disabilities, the report found.

King County’s two adult jails — one in downtown Seattle and one in Kent, with an average of 1,950 total inmates — don’t have firm voting-access policies, per se, says William Hayes, director of the King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention (DAJD). “We have procedures.”

In other words, for now, there are fliers posted in the housing units, and voter access information is printed in the jails’ inmate handbook. The materials inform those in custody that while they’re awaiting a felony trial, or if they’re serving time on a misdemeanor, all they need to do register to vote or to acquire a mail-in ballot is to call the King County Elections office. DAJD also allows family members to send an inmate’s unopened mail-in ballot to the jail, and, once a ballot is ready to be cast, will pay for the postage. “We dont have polling stations or anything like that,” Hayes says, “but we try to accommodate the mail-in ballots as much as possible.”

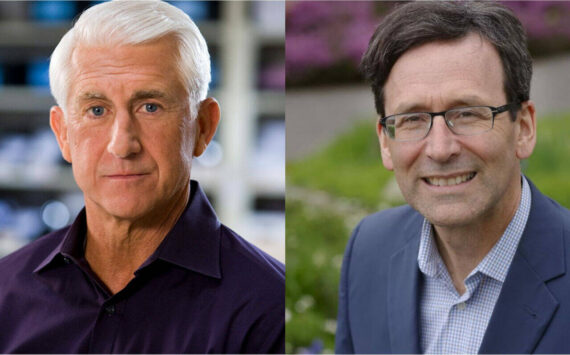

Still, the DRW report raised enough concern to spur Hayes and King County Elections Director Julie Wise to decide to meet up next week to turn those procedures into more formal polices.

The report “caused us to start going, ‘Hmm… what have we done in the past? What might we do in the future?” says Kendall Hodson, King County Elections Chief of Staff. It’s really only in the past few years that local jails have had the fliers and handbook pages they have today, she says, and even those, “to be honest,” mostly just “point [inmates] to call us to help them.” Some inmates awaiting trial do call King County Elections to request their ballot be mailed to the jail, but most calls have to do with uncertainties about voter eligibility, Hodson says; many people caught up in the criminal justice system aren’t sure if they can still exercise that right at all.

It’s a very common misconception, for instance, that having a felony on your record deprives you of the right to vote forever. Because laws vary so much from state to state, “There’s so much misinformation out there,” she says. “We are very inclusive here in Washington state with our voting laws.” Despite misconceptions, Washington’s convicted felons are eligible to register to vote again as soon as they get out of prison — even if they’ve still got court-ordered fines to pay, thanks to legislation passed in 2009.

King County Elections director Julie Wise “believes her job is to remove barriers to voting — whatever they may be,” Hodson adds. “When we think about barriers, this is certainly one of them.”