And that’s when I came up with the flying utensils.” A seemingly innocuous phrase, right? If the speaker is a Disney animator, you might be visualizing a charming sequence of movie magic. But no—the speaker is Brian De Palma, so this out-of-the-blue comment can only lead to something perverse. His fans will know that the notorious director is talking about Piper Laurie’s death scene in Carrie, his 1976 horror hit. On the page, the telekinetic Carrie gives her mother a heart attack. Speaking to us in the documentary about him, De Palma rolls his eyes over how uncinematic this would be. Why have a character simply clutch her chest and fall over when you could send an arsenal of flying cutlery toward her, crucifying the evil witch in her own contaminated house?

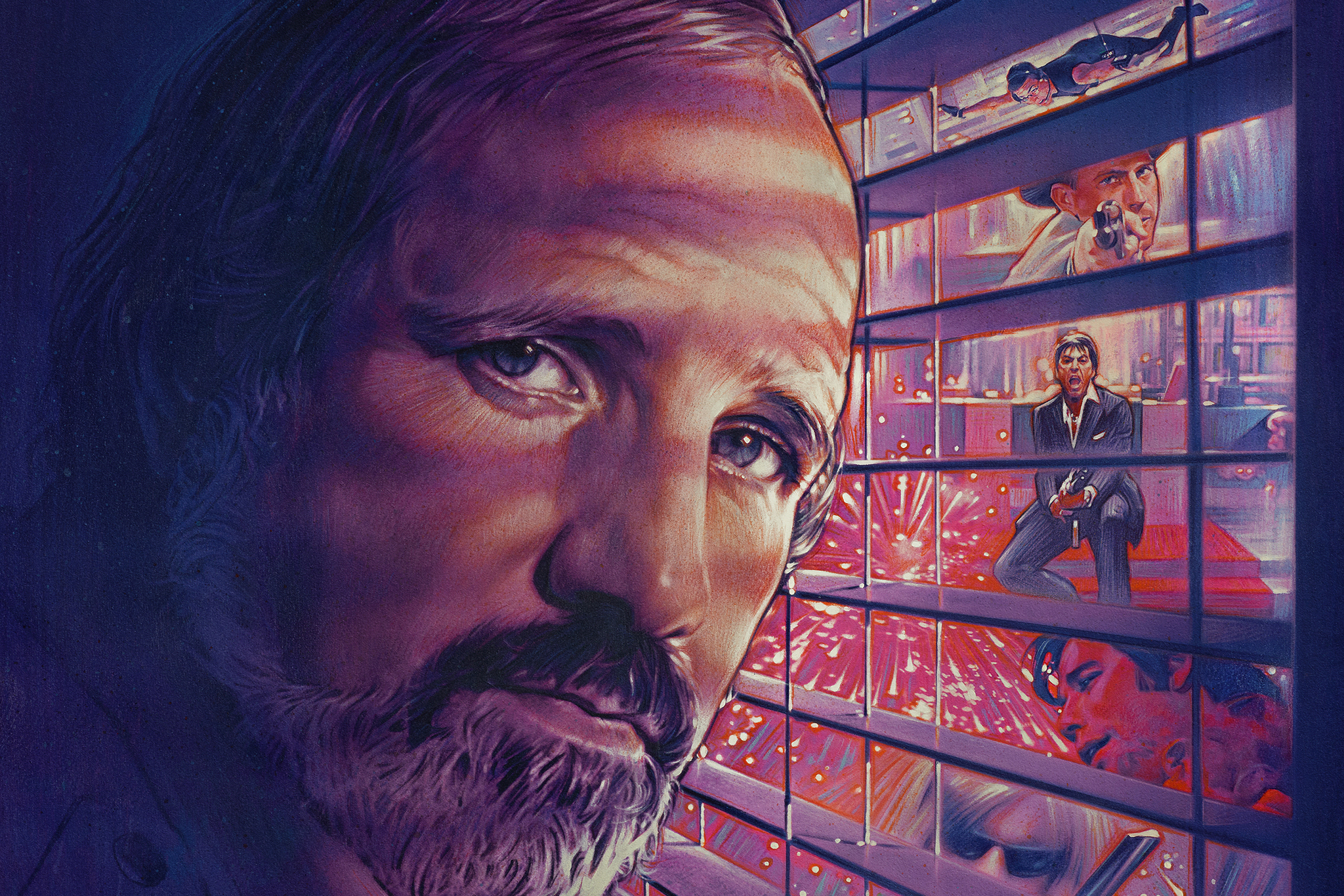

This is one of dozens of stories in De Palma, a feature-length interview in which the filmmaker, 75, tells anecdotes, copiously decorated with clips from all his films. The tidbit about Carrie is typical of the documentary at its best: It’s a colorful story, but it also underscores De Palma’s keen, sometimes lurid grasp of what cinema is. That scene in Carrie may be over the top, but it is cinematically alive in a way that De Palma’s better-behaved colleagues rarely touch.

The documentary’s creators, Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, are directors themselves. They take a chronological approach to De Palma’s career, starting with his childhood as the son of a philandering surgeon (he says he saw a lot of blood growing up) and his early underground films. If you only know De Palma as a Hollywood guy, his ’60s counterculture comedies like Greetings and Hi Mom! (both of which featured a nervy young De Palma discovery named Bobby DeNiro) will come as a surprise. He reminisces a bit about being one of the then-young upstart directors of the movie-brat movement that included his pals Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Francis Coppola, but the emphasis here is less on life experiences than on the movies themselves.

There are good behind-the-scenes stories about how Cliff Robertson sabotaged Obsession, and how De Palma found master composer Bernard Herrmann for the low-budget horror flick Sisters (which in its own disreputable way may be my favorite De Palma picture). He acknowledges Hitchcock’s influence without seeming too embarrassed about it. But mostly the film is a hugely enjoyable seminar on How to Solve Moviemaking Problems, as De Palma describes the nuts and bolts of an elaborate shot from Carrie, or why it made practical sense that a murder weapon in Body Double should be a very, very long drill—how else is it going to pass through someone’s body and then through the floor so that blood can drip on someone in the apartment below?

De Palma had mainstream success with The Untouchables and Mission: Impossible, and he guided one legendary disaster, The Bonfire of the Vanities (he admits to compromising on that one in ways that doomed it). But when the dust settles, De Palma should be remembered for the violent, unhealthy little movies that once made him a household name. Dressed to Kill, Raising Cain, The Fury—these and others are feverish children of the night, full of rococo camera moves, garish color, and a surgeon’s eye for disease.

I am not one of De Palma’s diehard fans; there’s always been something tinny around the soul of his movies, and his lack of interest in the ordinary lives of human beings can be palpable. De Palma is the work of uncritical fans, and this may be the documentary’s shortcoming. Where François Truffaut brought a critic’s eye to his career-spanning book-length interview with Hitchcock (an inspiration for this movie), Baumbach and Paltrow are happy to let De Palma ramble—we don’t hear anybody else’s voice. Since De Palma himself isn’t going to talk about what drives the operatic nature of his style, that level of insight isn’t here. But as a cinematic appetizer platter of clips and stories, De Palma is a chance to gorge. If you care about movies, you’ll gobble this up with a knife and fork. De Palma, SIFF Cinema Uptown. Rated R. Opens Fri., June 24.

film@seattleweekly.com