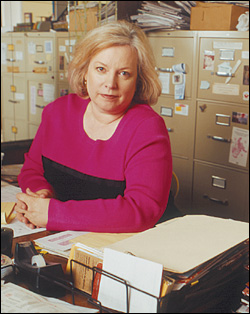

Computer-voting watchdog Bev Harris is squaring off with federal authorities over the government’s request for information about visitors to her internationally renowned Web site, www.blackboxvoting.org. While Harris is determined to resist the government’s investigation, a national expert on press freedom says the Renton muckraker will almost certainly face extensive fines or jail time if she refuses to cooperate.

In the past 20 months, Harris has become America’s leading critic of electronic voting (see “Black Box Backlash,” March 10). Her reporting on the problems with new computer voting machines has been a key component in a national, grassroots movement to safeguard voting. Her astounding discoveries have resulted in important studies by distinguished computer scientists. She has been leaked thousands of pages of internal memos from Diebold Election Systems, one of the country’s leading electronic voting companies. She is frequently cited by newspapers across the country and is a guest on national and local television and radio stations. Thousands of people visit her Web site and participate in its reader forums. Now, Harris claims, the government wants our names, forum messages, and computer addresses.

Following the advice of her lawyer, Harris will not talk publicly about the government’s investigation. Seattle Weekly used postings from Harris’ Web site and interviewed other people involved with the investigation to put together this account.

The investigation began last October, when VoteHere, an electronic voting software company in Bellevue, reported that a hacker broke into its computer network. VoteHere founder and Chief Executive Officer Jim Adler says, “We didn’t think it was a big deal.” Adler confirms, however, that the FBI and the Secret Service are investigating the matter. “A crime is a crime is a crime,” he points out. Adler says there was evidence that the hacker was politically motivated and was involved somehow in the leak of internal documents at Diebold—although he will not discuss specifics, at the request of federal law enforcement agencies.

Last September, Harris was the first person to publicly post the Diebold memos, which contain a variety of embarrassing internal e-mails, on the Internet. The resulting furor produced a wave of bad publicity for the company. (On April 30, California Secretary of State Kevin Shelley banned the use of Diebold’s voting machines in four California counties and called on the state attorney general to investigate the corporation for allegedly lying to public officials about testing and federal certification of its products.)

On blackboxvoting.org, Harris writes that in October, a month after she posted the Diebold memos, she was e-mailed a link that would take her to stolen VoteHere software. She didn’t click on the link, because she thought someone was trying to entrap her. Four months earlier, VoteHere had announced their intention to release their software for public examination. “Why would anyone in their right mind grab the stuff in some clandestine manner when it was being released into the open momentarily?” she writes.

VoteHere’s Adler says the company isn’t sure whether the hacker made off with its source code. He, too, however, expresses confusion about why somebody would steal something that was about to be publicly released.

Despite her reservations, Harris did follow up with a person who claimed to be the VoteHere hacker. She conducted a telephone interview with him but afterward felt even less sure of the veracity of his claims to have possession of the VoteHere source code. “I did not find him to be credible. It appeared to be an entrapment scheme,” she states. Harris also says the VoteHere hacker and the Diebold memo leaker are not the same person. “I am dead certain of this,” she writes.

On Jan. 9, Harris says, she had her first meeting with Secret Service agent Michael Levin about the hack. Levin would not confirm that he met with Harris, but he does acknowledge that there is an ongoing investigation and refers to Harris by her first name. Levin is the supervisor from the Secret Service for the Northwest Cyber Crime Task Force, an interagency law enforcement group that includes the FBI, the Internal Revenue Service, the Washington State Patrol, and the Seattle Police Department.

To date, Harris writes, she has had five meetings with Levin. By April 29, she was completely fed up. “This investigation no longer passes the stink test,” she writes. “I’ll tell you what it looks like to me: a fishing expedition.” Harris states that the Secret Service claims it is investigating the VoteHere hack but never spends much time on it while interviewing her. “Most of the time is spent on the Diebold memos, which they claim they are not investigating.”

Harris sounds the alarm about what the government wants her to turn over. “They want the logs of my Web site with all the forum messages and the IP [Internet protocol] addresses.” IP addresses are unique, numerical pointers to one or more computers on the Internet, making it possible to identify, or narrow the search for, a computer that has visited a given Web site. Writes Harris: “This has nothing to do with a VoteHere ‘hack’ investigation, and I have refused to turn it over.

“So, yesterday, they call me up and tell me they are going to subpoena me and put me in front of a grand jury. Well, let ’em. They still aren’t getting the list of members of blackboxvoting.org unless they seize my computer—which my attorney tells me might be what they had in mind.”

Harris also says Levin told her that he was on the same plane as her on one of the activist’s recent speaking tours. “What’s that supposed to do? Scare me?” she asks.

Harris obviously hopes that the information on her computer can be kept private because she considers herself a journalist. “[Y]ou can’t investigate leaks to journalists by going in and grabbing the reporter’s computer,” she writes.

But Lucy Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in Washington, D.C., isn’t so confident. Harris faces two key questions, explains Dalglish. First, is she a journalist? And second, can a journalist successfully resist a subpoena from a federal grand jury? Dalglish says that federal appeals courts, including the Ninth Circuit that has jurisdiction in Washington, have defined a journalist as someone who is collecting information to disseminate it widely to the general public. Certainly Harris is doing that. That she is not an employee of a traditional news organization—and that her Web site focuses on a very specific subject, voting security—would work against her legal claim of being a journalist, Dalglish says. But she thinks Harris could overcome those issues with a good lawyer.

When it comes to a federal grand jury subpoena, however, being a journalist doesn’t give you any immunity, Dalglish says. U.S. attorneys, the federal government’s chief prosecutors, can convene grand juries to present evidence to indict someone for a crime. In a grand jury proceeding, explains FBI Supervising Special Agent Greg Fowler, who oversees the Northwest Cyber Crime Task Force, there are no judges or defense attorneys. The U.S. attorneys present evidence and call and question witnesses in front of the jury, says Fowler. The jurors do not reach a verdict of guilty or innocent, he says, but, rather, vote on whether the evidence and witnesses presented support the indictment sought by the federal prosecutor. Since the proceedings of grand juries are secret, Fowler will not comment on whether Harris will be subpoenaed, as she predicts on her Web site.

If Harris is subpoenaed, however, Dalglish says being a journalist doesn’t mean anything. “In a federal grand jury investigation, there is almost no protection,” she says. “There is nothing more difficult to quash than a federal grand jury subpoena.” Dalglish says if Harris refuses to cooperate, she will almost certainly face judicial sanctions. “This is the classic situation where you get fined or go to jail,” she says. Dalglish says that if Harris is served with a subpoena, a good attorney would try to get it tossed out for reasons of relevancy—that Harris’ records have nothing to do with the VoteHere hack—rather than claiming journalistic immunity. If that argument failed, the identities of those of us who have visited blackboxvoting.org might wind up in the files of federal law- enforcement authorities.

In her last public summary of the investigation, Harris wrote, “Yeah, I’m not a happy camper. Taking the pulse of our democracy nowadays, it doesn’t feel very healthy, does it?”