If “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” makes one insane, then the Seattle Mariners are undies-on-their-head lunatics.

Since 2003, the team has hired five managers. Each was a former professional player with major league coaching experience. None lasted more than three seasons. Each finished in last place at least once. None finished in first. Now the Mariners have hired a manager again. And the man they picked is—I think you can guess—a former professional player with major league coaching experience.

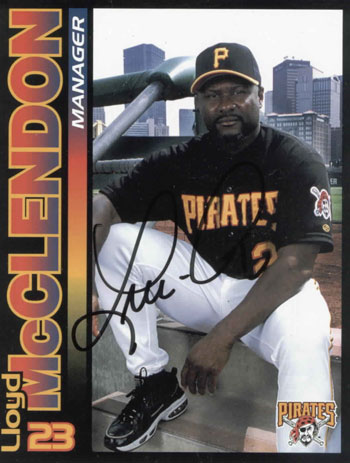

The reported finalists for the job included Ex-Mariner Joey Cora, “a great baseball man,” according to former boss Ozzie Guillen. Also Rick Renteria, an ex-MLB infielder and “tremendous baseball man,” according to former Astros manager Brad Mills. The man who won the job is Lloyd McClendon, a former MLB outfielder and manager. McClendon says of himself: “I’m a baseball man.”

What, you may wonder, is a “baseball man”? It means someone who has a long affiliation with the game and respect for its culture and is a staunch defender of Playing the Game the Right Way™. In other words, an absolute conformist.

The Mariners’ prerequisites weren’t unique. Most baseball managers are “baseball men.” Nearly all have played in the major leagues—86 percent of them since 1900, including 25 of the 2013 season’s 30 MLB managers. It makes sense: A player who reached baseball’s highest level should have an advanced understanding of the sport. Who wouldn’t want to hire a former player?

An NFL team, that’s who. Twenty-four of the NFL’s 32 current head coaches never played in the league, including the Seahawks’ Pete Carroll.

Why would elite playing ability be more important for a baseball manager than for a football coach? There is no reason, just circumstance. The difference between the two sports is in the path to getting the job.

Football coaches can prove their ability at the high school and college levels. Win at these competitive jobs and you can emerge from utter obscurity into a shower of cash—like Chip Kelly, an assistant at the University of New Hampshire who developed an innovative hurry-up offense, won 46 games with it at the University of Oregon, and is now paid $5 million a year to coach the Philadelphia Eagles.

Major league managers, by contrast, train for the job in the minor leagues, where the primary goal is not winning games but preparing young players for the majors. That means playing exactly the way the big club does. A minor league manager is no more likely to try something as unorthodox as Kelly’s offense than a commercial airline pilot is to fly a loop-de-loop.

Football’s path rewards innovation. Baseball’s rewards conformity.

As in any competitive industry, in football the best idea wins. Young baseball managers may have ideas, but they aren’t allowed to try them. Thus innovation in baseball moves at a glacial pace. Take relief pitchers (in the Mariners’ case, please!). Only now, after nearly 100 years of experimentation, has the simple idea of using one hard-throwing pitcher to protect a lead in the final inning—a “closer”—been adopted by all teams.

And, in keeping with baseball’s conformist style, I do mean all teams. In 1994, Lee Smith became the first pitcher to have more than 75 percent of his saves in one-inning appearances. In 2013, 93 percent of saves were of the one-inning variety. You’d think baseball managers—who are, as far as I can tell, genetically distinct—would deploy their relief pitchers in a variety of ways. Some would use their closer for a few innings, as was common in the 1970s and ’80s; some would choose a closer game-to-game depending on the situation; some would use their best reliever against the opposing team’s most dangerous hitter. Instead, every manager in baseball designates a single man as his closer, and calls on him only when his team leads in the ninth inning or later. All other approaches—even those that were successful within living memory—are outre.

Football’s forward pass has a similarly long history and is more common now than it was 60 years ago. But there is still a wide variance in how teams use it. The 2013 Seahawks throw about 26 passes per game, 16 fewer than league-leaders Detroit—and 10 fewer than the 1950 Los Angeles Rams.

Change is so rare in baseball that when it happens, they make a movie about it. Moneyball dramatized how statistical analysis has transformed the way teams measure player performance. But if you want to catch up on the latest on-field strategy, you may as well watch The Babe Ruth Story.

The wildest strategic innovation of the past 30 years lasted just seven games. In 1994 Tony LaRussa, then in his 16th season as a major league manager and recognized as among the best in the game, abandoned the traditional five-man pitching rotation in favor of a three-squad rotation. Responsibility for pitching rotated among the three squads, each consisting of three pitchers. In the first seven games of the new system, the A’s lost six times. LaRussa called it off.

Still, despite all this tradition-worshipping resistance, now that the Moneyball-minded are increasingly being hired to head major league front offices, it follows that radical changes in baseball tactics are inevitable. And if there’s a team with a reason to try them first, it’s the Mariners.

With plummeting attendance, pathetic performance, and repeated managerial mishires, the Mariners should have cast a wide net. Instead, they re-ran the same type of search they’ve done the past five times with zero success? To steal another famous quotation: “He who rejects change is the architect of decay.”

sportsball@seattleweekly.com