“When Tim [Walsh] quit…that was just it,” says David Bazan. That was the tipping point for his decision to dismantle indie-rock band Pedro the Lion after 10 years. Though a rotating cast of talents contributed to the band, Walsh and Bazan were the only official members.

“I couldn’t do it anymore,” he says. “It just meant me trying to find two other dudes and going back on the road, pretending like nothing was wrong.”

Bazan began making music as Pedro the Lion when he was in college. It’s the project he’s best known for, though he’s played in many (from Seldom to Starflyer 59) and gone out on unconventional excursions with the synth-based Headphones. But regardless of his knack for witty, honest lyrics and strong, largely fictional first-person narratives, Bazan’s work with Pedro the Lion was often overshadowed by their reputation as a Christian band. Though he was a somewhat outspoken Christian and the lyrics contained spiritual imagery, Bazan himself did not think of Pedro that way at all. But it wasn’t the first time he’d experienced a conflict between music and spiritual beliefs.

“He was walking in the hall, and I recognized him and he recognized me,” says Bazan of his first encounter with fellow Seattle-based singer-songwriter Damien Jurado at Shorewood High School. “He was listening to his Walkman, and I asked what he was listening to and he said Pillars of Humanity by the Crucified, and I happened to have the same CD in my pocket.”

“After being introduced to Dave, who I immediately thought was too nice to be into hardcore music, we became friends right away,” recalls Jurado. “We practiced and formed a new band the same day we met.”

Ironically, though, it wasn’t Christian music that their first band, the Guilty (nor second band, Coolidge), played—something Bazan felt a bit at odds with at the time.

“I had grown up with this idea that music’s purpose was to prosyletize—to try to convince people to become Christian,” he says. “I was slowly growing out of that idea, but still going to church and considering myself a Christian.” As a drummer, Bazan’s solitary function in both the Guilty and Coolidge gave him a chance to express himself creatively without, he says, “having the opportunity to fuck it up by writing lyrics—which I would have done at that point.”

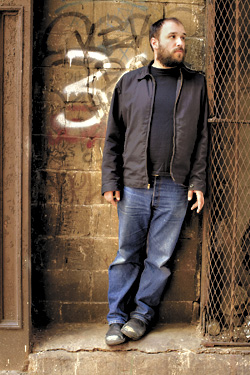

In Pedro, though, his capacity was much more dynamic. As the driving force behind the project, he juggled nearly all of the instruments on the records, as well as the great majority of the songwriting. Naturally, his craft matured exponentially. But the name David Bazan still means little to most without the Pedro the Lion association. Yet that’s right where he is these days—immersing himself fully in the art of solo performing.

Bazan’s played close to 200 dates since the Pedro breakup in 2005, sharing bills with Ben Gibbard, Vic Chesnutt, and Will Johnson of Centro-matic. Without the shield of a full band, his focus became refining his performance. He even videotaped himself onstage each night, watching the films over and over like an NFL quarterback looking to improve.

All of the self-scrutiny and training prepared him to face the bright lights alone. This summer, in the loft space above the Anne Bonny on Capitol Hill, I watched as Bazan played entirely unplugged, delivering most of his Fewer Moving Parts EP. Though he was remarkable before, Bazan’s songs are now striking, belted from his inner core. They slice through a room, the narratives riding atop his deep baritone, which crackles like burning leaves. Played solo, songs like “Selling Advertising,” a direct jab at Pitchfork founder Ryan Schreiber, take on a biting, sarcastic tone that would otherwise be lost among the din of a full band. “Fewer Moving Parts” seems to parallel his decision to go solo with its lyrics: “Cause I do and I don’t think I’m better off alone/Man I could have/Had a big sound/But I love to/Let my friends down/Fewer moving parts/Mean fewer broken pieces.” These songs offer revealing, autobiographical content that Bazan hasn’t previously been known for.

His forthcoming full-length debut, however (David Bazan’s Black Cloud, Barsuk, 2008) will likely change that perception. As he says in “Fewer Moving Parts”: “Every other start requires a brand-new thesis.” Thus, many of the new songs are a complete shift from the fictional topics of his previous work to raw, personal territory.

“All of the songs are about my wife and daughter, about drinking, and sort of poking at the idea of the existence of God—does he, or doesn’t he?” says Bazan, who, after extensive exploration, now considers himself agnostic.

“I have faith that hell does not exist,” he muses. “And I have faith that to the degree God does exist, he’s not this vindictive little bitch Christianity has made him out to be.”