Shoreline-schoolteacher-turned-director Michael Hoffman thinks his new Michael Keaton movie, Game 6, contains a metaphor for the just-concluded Sundance Film Festival, to which he returned in 2005 after a long absence. Keaton plays a playwright whose ideals have just struck the iceberg of reality. “He’s kind of on a downswing,” Hoffman explained at his posh Park City, Utah, hotel, “and now he’s written something about his childhood and his family, so it’s the first thing he’s ever written that he really cares about. Then he finds out his lead actor, who’s gone to Borneo to do a commercial, has contracted a parasite that’s affected his brain, so that he can’t remember any lines. They’re basically eating his play, eating his creation! It walks this line between realism and paranoid fantasy.”

In the eyes of many movie idealists, Sundance is a paranoid fantasy come true, an art mecca devoured by a commercial mecca. Once the preserve of purists who decried Tinseltown philistines and revered long, slow movies about long, cold pioneer winters, now it’s a place where $16 million deals are struck hot and fast while Paris Hilton dirty-dances with Pamela Anderson prior to picking up free underwear at Sundance’s innumerable star-fucking freebie emporiums. It’s the best way to expose brand names to the widest possible audience, whether the product is a gritty indie flick or a pricey brassiere. Even the sincere get seduced, says Hoffman: “I’m not doing much bewailing—I got this coat!”

He may get more than that. Current Oscar hopefuls Catalina Sandino Moreno and four of the documentary finalists went from nonentity to the top via Sundance, as did Sideways star Paul Giamatti in 2003’s American Splendor. If the fest has seen bigger single hits back at the dawn of Soderbergh and Tarantino, it’s been spawning more and more smaller ones lately, like last year’s Napoleon Dynamite, Super Size Me, Garden State, Saw, Open Water, Control Room, and The Motorcycle Diaries.

Keaton, who’s rather on a downswing in real life, could use some highbrow succès d’estime from his Sundance visit right now; so could Kevin Costner and Joan Allen in the melodrama Upside of Anger; Adrien Brody, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Keira Knightley in the amnesia thriller The Jacket; Pierce Brosnan in his madly popular, image-changing The Matador; Glenn Close (whose neck looked oddly older than her beautifully youthful face) in the chick flicks Nine Lives and Heights; and Daniel Day-Lewis (who now wears a Unabomber beard) in his wife Rebecca Miller’s back-from-the-’60s drama The Ballad of Jack and Rose.

Sundance buzzsters predicted good things for Craig Lucas’ adaptation of his own Hitchcockish play The Dying Gaul, with indie saints Patricia Clarkson and Peter Sarsgaard, and great things for the trendy L.A. ethnic-dance smash Rize, directed by David LaChapelle, who threw the week’s happeningest party and then entertainingly got arrested for protesting the ejection of two starlets from the club where Paris and Pamela did their bump and grind.

In the Michael Moore era, even documentaries inspired hard-nosed horse-race speculation. I overheard two suits calculating, “Murderball [about paraplegic rugby players] will do $10–$20 million— if they do everything right!” Alas, The Fall of Fujimori, about the Chilean president whose exploitation of terrorism for democracy-crushing political gain startlingly parallels Bush’s, won’t do business. Place your bets instead on the heroic penguin-migration documentary and Winged Migration wanna-be The Emperor’s Journey; urbanely ursine director Werner Herzog’s grisly biopic Grizzly Man, incorporating a fanatic’s own footage of his fatal attraction to Alaskan killer bears; and Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room—and 10 times as much on Inside Deep Throat (reviewed next week), whose co-star Harry Reems now lives large as a Christian real-estate agent in Park City.

My own three favorites from Sundance 2005 may not blitz the cineplexes, but they show that the festival’s indie heart can still beat true and strong despite the avalanche of bling and glitz. When release dates are set, don’t miss Thumbsucker and Hustle & Flow, and trample your own dad to see The Squid and the Whale (which is all about dad trampling). They introduce skyrocketing new stars and send familiar faces to unheard-of new heights.

Thumbsucker has the gentle off-kilter charm of early Cameron Crowe, or of the late indie rocker Elliott Smith, who contributed to the soundtrack. Newcomer Lou Pucci plays the teen hero whose shaky sense of self keeps him from renouncing childish comforts. His rivalrous, self-doubting ex-jock dad (Vincent D’Onofrio) is peeved about his son’s thumb habit, but once the kid discovers teacher Vince Vaughn’s debate team, he’s a changed man. Keanu Reeves redefines himself as the thumbsucker’s hugely amusing New Age dentist, and Tilda Swinton is luminous as the hero’s mom, a rehab nurse who treats a TV star who’s more arrested than her son. Thumbsucker is fumbling and tentative, but this is its glory.

Pucci has a future, but nothing like Terrence Howard’s, who co-stars in George C. Wolfe’s black-nostalgia vehicle, Lackawanna Blues, and soars to casting directors’ A-list as an ambitious pimp in the rap-to-riches flick Hustle & Flow, the festival’s biggest hit. The story is formulaic, and it demands plenty in the way of suspension of disbelief (you’ll be enlightened to learn that pimps are feminists who regard their best hos as brothers). Howard’s mournful, moral, yearning face ignites the screen and never cools down. The rest of the cast is up to his game. If you think you hate rap movies, you’ll probably still like this one—it’s not quite all the way to 8 Mile, but it’s a 6 Mile, easy

The most impressive debut at Sundance was Wes Anderson protégé Noah Baumbach’s wickedly, heartbreakingly funny divorce drama, The Squid and the Whale. It’s an exhilarating evisceration of Baumbach’s real-life father, Jonathan, a brilliant literary critic and fiction writer who taught at the UW in the 1970s and split with Baumbach’s mom, the more brilliant Village Voice critic and fiction writer Georgia Brown, in Brooklyn’s Park Slope in the mid-1980s. As a character assassin’s portrait of Baumbach senior, Jeff Daniels has never been better. If anything is known, he knows it—and lets you know you don’t, even if you know better than he does (especially if you’re his rising-star wife, deftly played by Laura Linney). He’s so competitive he can’t let his prepubescent son (played by Kevin Kline’s talented real-life son Owen) win at Ping-Pong; and he causes his brittle, worshipful, Noah-esque teen son (also-talented Jesse Eisenberg) to go around bad-mouthing Dickens novels he’s not yet read and belittling angelic girlfriends right out of bed.

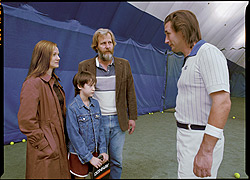

Some Sundancers made rote comparisons with Woody Allen, but they’re being blind and lazy—Baumbach (who previously created 1995’s Kicking and Screaming) is his own man. His style with camera and keyboard is jumpy and distinctive, and way more coherent than producer Anderson’s. The film’s sole weak spot, despite Linney’s characteristic genius, is the vaguely drawn mom role. She’s too simply the good guy, even though she sleeps around chronically and dumps dad for a tennis-pro mensch (winningly, grinningly limned by Billy Baldwin). A friend of the family tells me that Baumbach simply hasn’t worked through his mom worship the way he’s analytically overcome his now emphatically no-longer-extant dad worship. No matter: This amazingly bad (yet magnetically fascinating) dad is enough to make Whale a time-capsule keeper.

The dad character keeps giving everybody unsolicited advice about their writing. I asked Baumbach whether his dad gave him any notes on his script. “I wouldn’t show it to him,” he said. And how does his dad feel about his devastating portrait? “I think my father probably thinks of it the way Erin Brockovich thought of Erin Brockovich—as a sort of tribute.” This I doubt. But the film is one hell of a tribute to his son.