Don’t even try to argue with a vegan, because you’re not gonna win. Just walk away from the buffet table, smiling and nodding politely, until you’ve got a clear path back to the chicken wings.

As the president prepares to plant a vegetable garden at the White House, food has never been more political than it is today. And at the Naderite left of the dining spectrum sit the vegans, whose militancy—thanks to the Skinny Bitch series and a flood of other new vegan cookbooks—is now going mainstream. In support of its creed (no meat, no eggs, no dairy, sometimes no fish), the vegan militia can quite reasonably point to global warming, the obesity epidemic/world hunger paradox, recent food-contamination scandals, factory farming, and genetically modified monoculture crops. From there, it’s a short step to backyard chicken coops, and another to adopting those hens as pets and forsaking their eggs entirely.

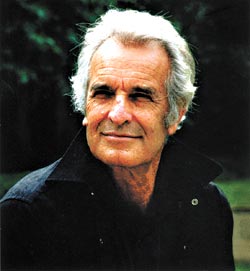

Granted, this was an even shorter step for ex-psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, raised vegetarian and lately an animal-rights activist and author. Now he travels from barnyard to kitchen in The Face on Your Plate: The Truth About Food (Norton, $24.95).

“Chickens are funny, curious, affectionate, stubborn, ingenious companions,” he writes of his two family pets. “What I learned from living with them is that there were giant characters inhabiting their small bodies, and given the chance, they were happy for us to see them, get to know them, and become friends with them.”

Now Masson is no dummy. He mentions—in his book’s very first sentence—that he was once a professor of Sanskrit. His Harvard degrees follow close behind, along with his brief stint running the Freud Archives (which prompted Janet Malcolm’s devastating New Yorker takedown and 1984 book, resulting in Masson’s epic, unsuccessful libel suit). This short book is amply footnoted and studded with concepts like anthropomorphism and the pathetic fallacy. Masson will never say that chickens—or cows or fish—have human feelings or cognition. But he starts from the position, advanced in his prior books, that animals have an emotional life.

And from there comes the kicker, as Masson describes poultry plants: “It is hard to avoid thinking of them as concentration camps for chickens.”

This is when the startled non-vegan retreats from the buffet table. You don’t want to go there, but Masson—who was born Jewish—goes there immediately. He ropes in Elie Wiesel and yields the following thesis:

“The ability to imagine ourselves into the minds and bodies of ‘others’—whether humans we term different from us (Down syndrome children; Alzheimer sufferers; the so-called mentally ill) or the animals we use for our food—is of central importance, because the failure to do so is precisely what led to the horrors of Auschwitz.”

OK, then. Masson is hardly the first to employ a slippery-slope moral argument, but we’re more accustomed to hearing it from the right rather than from a cosmopolitan intellectual and man of the left. And if you don’t buy that argument, or find it offensive, the lapsed Freudian offers another: We’re all in denial about the cruelty of the animal-based food system. “As with child sexual abuse,” Masson asks rhetorically, “why did society take so long to acknowledge it?”

(This links back to Masson’s controversial tenure at the Freud Archives, when he argued that Freud—and especially his followers—had suppressed evidence of such abuse. That, he posited, was the real cause of neuroses, not penis envy or castration anxiety.)

That there is violence and suffering in our industrial food production is hardly news. Masson cites Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation. He even quotes local chef Tamara Murphy, of Brasa, who spoke in The New York Times about “the betrayal” felt in raising and then slaughtering one’s meal. But if you know you’re betraying an animal, how can you be in denial?

Well, The Face on Your Plate only runs 200 pages; it’s a long-form argument sourced from Google News, not the philosophy department library. (Masson now lives in New Zealand.) And much of what he reports, or repeats, is quite sensible. Michael Pollan, Marion Nestle, and Alice Waters have already persuaded us, and him, about the virtues of fresh, local, and sustainable eating. Here in organic, green Seattle, we’re already opposed to factory farming, fish farms, and excessive food miles.

But that’s not enough for Masson. We must feel shame for the way we eat. And since he can’t tell us anything new about our food system, he’s selling us something quite old. Back in 1993, before embracing the animals, Masson recounted his parents’ (and his) devotion to a mystic leader in My Father’s Guru. Later he fell under the sway of Freud (and out of it). Yet while belonging to no church, Masson still requires sin. And he, like the gurus he once followed, must dispense a means of absolution.

Go ahead and eat, he says, once you’ve cleansed your soul.