THURSDAY, SEPT. 5

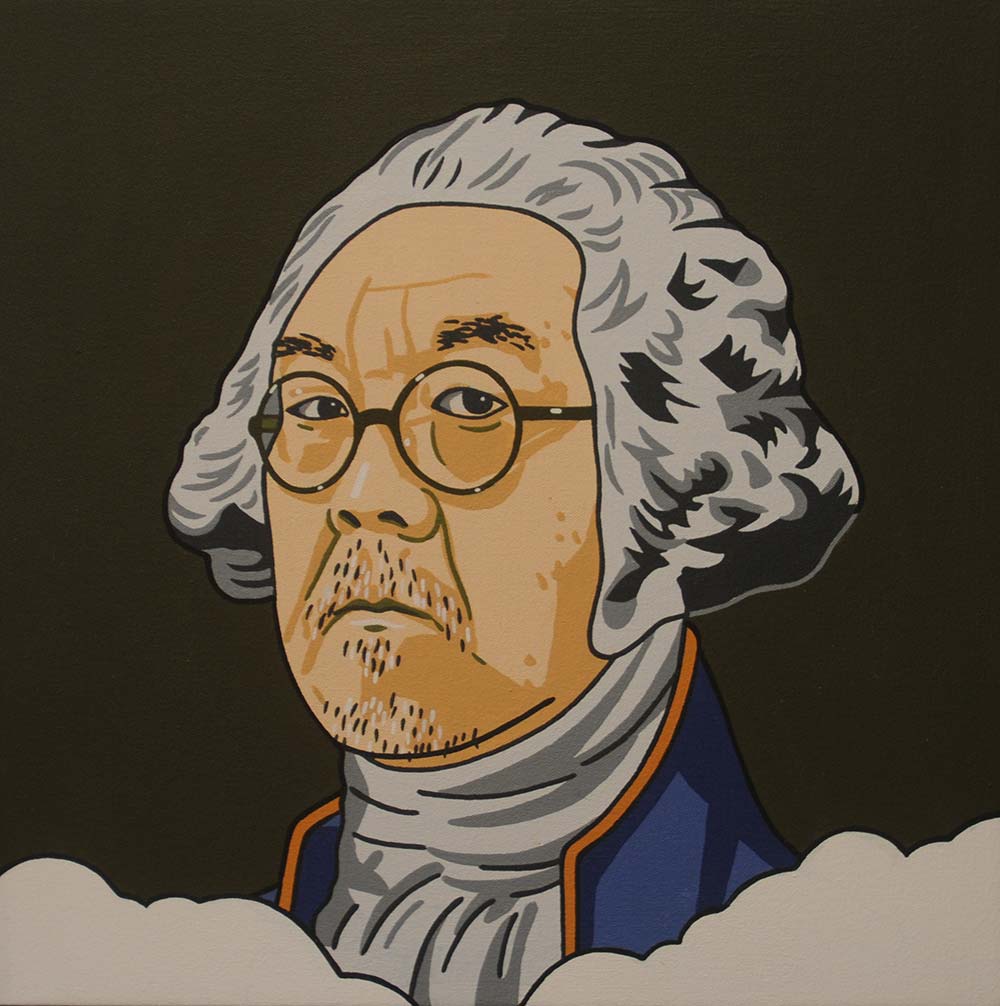

Roger Shimomura

OK, so the opening reception for Roger Shimomura’s An American Knockoff show was during mid-August, but who was in town for that? During tonight’s First Thursday art walk, which kicks off the fall season among downtown galleries, you should definitely stop to see the large new paintings by the veteran artist. Shimomura has long combined colorful Pop Art with personal history. Born and raised in Seattle, illegally interned with other Japanese-Americans during World War II, and today a retired teacher at Kansas University, his influences include comic books, Disney cartoons, and traditional Japanese art. Where he fits into that East/West clash, or doesn’t, has always been central to Shimomura’s work. He frankly acknowledges his hybrid status, and here he’s literally fighting his way through Asian and American iconography. He karate-kicks samurai and Wonder Woman; dresses like Superman, Sailor Moon, and George Washington; even intermingles with Chinese Communist poster figures. If others were once confused about where he came from (always that contentious question), he embraces the confusion, mocks it, and makes it his own. (Through Sept. 28.) Greg Kucera Gallery, 212 Third Ave. S., 624-0770, gregkucera.com. Free. 6–8 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

Jonathan Raban

Though forever branded as a newcomer and outsider here, because Seattle never lets you forget that, Jonathan Raban is actually our city’s preeminent essayist, whose voice often carries back East and to the newspapers of his native England. (Only The New York Times’ Timothy Egan has a bigger soapbox.) Raban came here in 1990, which now makes him a veteran among the Northwest literary tribe. New in paperback, his Driving Home: An American Journey (Sasquatch, $20) collects two decades of work in 600 pages. Upon settling here, Raban made every effort to learn the new trees and birds, to master the environment before the people. “The immigrant needs to grow a memory, and grow it fast,” he wrote for The Telegraph 20 years ago. “Somehow or other, he must learn to convert the uncanny into the homely, in order to find a stable footing in the new land.” With that footing in place, Raban’s gone on to chronicle the peregrinations of Ted Roethke, his own frequent road trips, sailing, the depression of Capt. Vancouver, our city’s dot-com bubble (remember?), the election of Obama, and more. Driving Home is a pleasurably baggy collection from an acerbic, sometimes crusty writer, well suited to the nightstand. No one but Raban has written so much in such a short time on his adapted hometown—not that that makes him a native, of course. Seattle Central Library, 1000 Fourth Ave., 386-4636, spl.org. Free. 7 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

FRIDAY, SEPT. 6

Heaven’s Gate

Now running over three and a half hours, the restored version of Michael Cimino’s 1980 post-frontier Western has at least partially redeemed its old reputation as a studio-destroying fiasco. An entire book, Steven Bach’s Final Cut, was written on how the movie brought down United Artists, but to be fair, broader market forces were at work back then. Regardless of Cimino’s costly, unbridled auteurism or the negative reviews (“a woozy, morose mixture of visual virtuosity, overarching ambition, and slovenly writing . . . the work of a poseur who got caught out,” said Pauline Kael), long period pieces were simply going out of style. Westerns, especially, had fallen out of favor. It’s worth remembering that Apocalypse Now was equally profligate and self-indulgent, but the recent context of the Vietnam War gave Francis Ford Coppola’s movie that much more deference—as Cimino’s prior The Deer Hunter had also received from critics. That said, the restored Heaven’s Gate—reissued last year on DVD from Criterion—is never going to be a great movie. It certainly looks great, thanks to cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, but Cimino’s script fails to get a grip on the class conflicts of 1890s Wyoming. His story is based on the actual Johnson County War between ranchers, here represented by hired gun Christopher Walken, and immigrant settlers, here defended by Kris Kristofferson. (Isabelle Huppert plays the brothel owner caught between them.) There’s so much historical detail in Cimino’s vision that the historical conflict gets lost—often beautifully so. In a shoot that ran almost six months, Cimino forgot that editing begins at the typewriter, not on location. (Through Thurs.) Northwest Film Forum, 1515 12th Ave., 267-5380, nwfilmforum.org. $6–$10. 7 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

MONDAY, SEPT. 9

Davy Rothbart

You could call Davy Rothbart one of the children of David Sedaris, since the stories in his My Heart Is an Idiot (Picador, $16) are both biographical yet so entertaining as to inspire skepticism. Nothing can be verified as Rothbart ransacks his past for vignettes he can use in his frequent stage performances. (He’s a regular road warrior in support of Found magazine and its anthologies.) Just as Rothbart made his literary reputation by collecting and publishing the written scraps of total strangers, he’s also a near-compulsive collector of experience, a man who always wants to talk to strangers. During one low moment in a collection that’s equally a non-chronological memoir, Rothbart regrets his addiction to novelty and penchant for drinking, but there’s a fundamental generosity to his ADHD antics. He sleeps on pool tables; wakes up naked in a New York City park; discovers a corpse in pool after cheating on his girlfriend (while a tarantula watches “like a black, severed hand”); picks up hitchhikers and gives them money; bonds with bus passengers returning to Manhattan after 9/11; and even stalks a scam artist with the intent of dousing him with bottled urine. Yet Rothbart never abuses or shames those who confide in him (names have been changed). Even the intended victim of his pee-bottle attack, who profits from fake literary contests, arouses Rothbart’s unexpected sympathy. Is it plausible that they should accidentally meet in a hotel room, drunk, smoking pot, and watching an Orlando Magic game on TV? And did Rothbart really inflict such perfect, non-piss punishment upon the fellow? Maybe not, but this version of events plays better. Lucid Lounge, 5421 University Way N.E., 634-3400, ubookstore.com. Free. 7 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

TUESDAY, SEPT. 10

Jamie Ford

His best-selling first novel, 2009’s Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, was set in Seattle’s Chinatown, and Jamie Ford returns to the same small enclave during a different era for his Songs of Willow Frost. Set in the ’20s and early ’30s, the sentimental tale follows a 12-year-old orphan, William Eng, who believes a Chinese-American film star to be the mother who abandoned him (Willow Frost being her stage name). Today based in Montana, Ford—his great-grandfather changed the family surname from Chung—has roots in Seattle, where he researched the many surviving landmarks that figure in young William’s quest. From the 5th Avenue Theatre to the Sacred Heart Orphanage in Laurelhurst to the Bush Hotel in today’s ID, the book provides readers a veritable walking tour. (In fact, the Wing Luke Museum offers just such a tour for Bitter and Sweet, which Book-It adapted last year in a well-received stage production.) Willow Frost bears the pungent traces of the Great Depression, with breadlines, Hoovervilles, and Skid Row flophouses where the residents are warned to use the toilets only at low tide. Casual racism is the norm, and William everywhere pushes against boundaries of class and ethnicity. If Willow really is his mother, and there is some doubt, she’s an exemplar of Hollywood assimilation: playing the sultry “exotic” stereotype to escape the hardships of her mundane old past. No wonder William wants to follow her. Town Hall, 1119 Eighth Ave., 652-4255, townhall seattle.org. $5. 7:30 p.m.