The Frye’s new chief curator, Robin Held, continues to sneak radical art into the formerly conservative Frye like a dissident smuggling Bibles into the old Soviet Union. Her most recent contraband: “The Retro-Futuristic World of NSK,” (through July 31; 206-622-9250) from the art collective that has been creating visual art, graphic design, music, and theater in Slovenia since the early 1980s (when it was part of Yugoslavia).

Neue Slowenische Kunst was born as a collective, multidisciplinary movement to create art that makes people in power uncomfortable. Functioning as its own “state in time,” it issues passports and has created its own “embassies” during various performances and exhibitions around the globe. A postmodern state without borders, the Ljubljana-based NSK adopts the imagery and language of nationalism and perverts it, putting uniforms and kitsch into the service of artistic rebellion.

One “branch” of NSK is the band Laibach, founded in 1980 and quickly banned by the Yugoslav authorities. Laibach (which takes its moniker from the name German occupiers gave to Ljubljana during World War II) is an industrial heavy-metal band with a fondness for military uniforms (some of which are on display at the Frye), Henry Rollins–style guttural singing, and deafening drums. One infamous Laibach song transformed Queen’s anthem “One Vision” into a sinister parody of Nazi propaganda. “One flesh, one bone, one true religion” takes on a whole new meaning when sung in German by guys in jackboots. Though this has brought inevitable accusations of neofascism, NSK is resolutely against all forms of authority.

NSK has also produced a large body of avant-garde theater and performance work, some of which is on display at the Frye, including a video of the unfurling of a huge black fabric square on Red Square in Moscow in 1992.

But most important for the purposes of this show is the visual art department of NSK, a group known as Irwin, which began in 1983. Dressing in suits and ties, the artists in Irwin look to the American corporation as its exemplar—not surprising in a group trying to subvert culture in a formerly communist state. But in Irwin’s work and process, there’s a genuine nostalgia for the idea of collectivism.

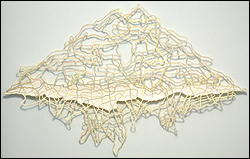

The group has generally avoided giving individual credit to its members, instead approving each piece and stamping it with the corporate brand of Irwin. Like pop art, which has much in common with the NSK movement, Irwin is about appropriating imagery. But in place of Campbell’s soup cans or Brillo pad boxes, Irwin traffics in totalitarian kitsch and images lifted from art history.

Ignorance-is-bliss, communistic kitsch abounds everywhere in Irwin’s work: in silhouettes of hammer-wielding workers, in paintings reproducing the agrarian symbol of the sower, in huge images of heavy-antlered deer. Much of Irwin’s art is about turning this kitsch back against the state. The graphic design branch of NSK once won a national contest in 1987 to design a poster promoting communist youth in Yugoslavia. A scandal erupted when someone noticed it was simply a reworked Nazi propaganda image.

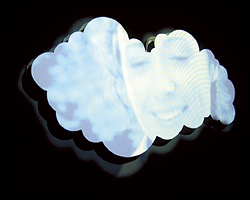

But more than simple postmod appropriation, Irwin has a sincere utopian streak to its mission. It embraces Kasimir Malevich’s notion of art as the “materialization of a pure idea.” Indeed, Malevich, the early 20th- century modernist, is a huge touchstone for Irwin. Many works incorporate Malevich’s minimalist black cross and transform it into a kind of talisman. It reappears throughout the Frye show, in elaborately sculpted frames, in stark abstract paintings (oh, how the anti-abstraction Fryes must be flailing in their graves), and even as a kind of proto-fascist armband on cuddly teddy bears.

Irwin is deft at using kitsch to skewer the excesses of communism and capitalism alike without ever being polemical. It’s designed to make lefty arts patrons and right-wing politicians equally nervous.

This is not to say that all of NSK’s endeavors hit their mark. After the success of the Slovenian Spring in 1992, it’s unclear what sort of role the art collective should play. Some of the pieces offered up in the Laibach section of the exhibit seem a bit hackneyed. But you can’t expect a collective endeavor like NSK to be without stumbles. In fact, it’s astonishing that the artists in NSK have managed to stay together and produce a consistent body of avant-garde work for nearly 25 years.

It’s fascinating to watch an artistic movement with such utopian aims negotiate the intensely commercial art world. Armed with a Duchamp-like playfulness, NSK refuses in many ways to agree to what the West has demanded of its artists: originality, authorship, and national identification. NSK’s subversive state is unsettling, and to more than just the staid Frye Art Museum crowd.