In the border town of Nogales, Sonora, where buses drop off the newly deported every few hours on the American side, almost everyone seems to have been through Operation Streamline, a U.S. Border Patrol program that aims to hit all migrants entering the United States illegally with a criminal conviction.

There’s the street peddler, Gary, selling multicolored balloons and pinwheels to the cars lining up to cross into Arizona at the main port of entry. He was on his way to San Francisco when he was caught near Sasabe and put through Streamline’s wringer.

“It was a bad experience,” he says (all the Streamline defendants interviewed in this story spoke Spanish). He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor count of entering the United States without permission, a conviction the Border Patrol believes operates as a deterrent to illegal immigration.

But Gary is determined to cross again. The conviction will not dissuade him, he vows.

Near where Gary’s plying his trade, a line of men and women file through a gated passageway into Mexico, after stepping off one of the many buses that deliver deported migrants every couple of hours to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Most of the new deportees passing by describe having been shackled hand and foot for the Streamline court in Tucson. Many have just spent 30 days or more at a facility in Florence, one run by Corrections Corporation of America, a private prison behemoth that jails Streamline convicts for the U.S. goverment.

One clean-cut young man named Luis stops for a moment. He was apprehended in Arivaca, Arizona, on his way to Minneapolis to work as a roofer. He has an aunt up there, he says.

Would he try crossing again, even though he might get more time if caught?

“Yeah, I will,” he promises, before moving on with the rest. “I’m not a fucking criminal. I just want to work.”

Several people say they felt as though they had no choice but to plead guilty during the Streamline proceedings that occur every weekday at 1:30 p.m. at the federal courthouse in Tucson. There, 70 people a day plead to misdemeanor illegal entry, or 18 U.S.C. 1325 of the federal code. Most receive time served. Others get up to six months in prison as part of a plea agreement with the Arizona U.S. Attorney’s Office, in which the more serious offense of illegal reentry, or 18 U.S.C. 1326, is dropped.

Champions of Operation Streamline argue that the migrants get a sweet deal: either time served — usually the one to three days they’ve been in Border Patrol custody — or 30 to 180 days, far less than they’d receive if convicted on a reentry charge. A conviction on 1326 is punishable by up to two, 10, or 20 years, depending on the circumstances of the individual.

Moreover, the Border Patrol maintains that Streamline, which began in 2005 in Del Rio, Texas, and spread to nearly every jurisdiction on the southwest border, is a success. The agency points to dramatic declines in apprehensions where Streamline has been in place.

But Streamline’s intended deterrent effect on illegal migration is not borne out by the Border Patrol’s own apprehension numbers. The program is a mega-million-dollar boondoggle that fattens the Border Patrol’s budget and enriches private corporations. It diverts resources from pursuing more serious crimes, such as human smuggling and drug and gun trafficking.

Also, Streamline’s many critics complain that the program is arbitrary and inhumane, violating the due-process requirements of the U.S. Constitution’s Fifth and 14th Amendments, as well as a Sixth Amendment right to the effective assistance of counsel. All for a program that is essentially unnecessary, as an immigrant’s removal through the civil administrative process already bars him or her from legal reentry for five years.

At a Nogales station for Grupos Beta, a Mexican aid agency that assists migrants when they come back across the border, the newly deported linger. The station sits next to a cemetery pockmarked with recent bullet holes.

A man named Jose says he was on his way to Texas when he was nabbed by the Border Patrol near Sasabe.

Jose did 55 days in a CCA facility, he says. He says his lawyer told him to plead culpable, or guilty. The 55 days he served won’t stop him from crossing again. He has a wife and children in Texas. He must go back.

Both Elena, 31, and Emma, 42, plan to return, too, eventually. Both women have family in the United States.

Elena did a month in CCA after going through Streamline. She was on her way to Salinas, California, when she was apprehended. Her husband and two daughters, 10 and 2 ½ years old, live there. Elena says she made money there by working in the fields, picking broccoli and lettuce. She hasn’t seen her family in five months.

Before her Streamline hearing, Elena was exhausted and hadn’t been afforded a shower. She says she’d only been given cookies and juice to eat by the Border Patrol.

Emma describes the Border Patrol’s throwing her cookies on the ground in front of her, instead of handing them to her. In court, the handcuffs hurt her wrists. She thought she had no option but to plead guilty. She got time served before getting bused to Nogales.

Her husband and two kids are in Orange County, California. Emma came to tend to a sick sister in Mexico and hasn’t been able to get back to her family for three years. She says she will keep trying.

“I’m scared,” she says. “But my family’s there.”

Asked whether her treatment was unfair, she says it was.

“We’re not criminals,” she says. “I don’t feel like a criminal.”

Though U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano claims the DHS (of which the U.S. Border Patrol and its parent agency, Customs and Border Protection, are a part) is targeting “criminal aliens” for removal, the Obama administration is creating criminal aliens through Operation Streamline.

Migrants — who once would have been removed from the country through a civil-administrative process and barred from legal reentry — now return home with a criminal record that could expose them to escalating punishment if they cross the border again to escape poverty, find work, and/or reunite with loved ones.

Streamline began as a “zero tolerance” approach to border enforcement during President George W. Bush’s administration. Before its advent in 2005, aliens apprehended by the Border Patrol generally were not prosecuted under existing criminal statutes.

Once migrants regularly began receiving criminal penalties for illegal entry, the Border Patrol claimed dramatic reductions in apprehensions in the Del Rio sector, where the program began. In 2006, Streamline started in the Border Patrol’s Yuma sector. Laredo, Texas, got it in 2007. And in January 2008, Streamline was initiated in the Tucson sector, where it’s estimated that nearly half of all illegal entries now occur.

Now in eight courts along the U.S.-Mexico Border, Streamline operates a little differently in each one. In some jurisdictions — including Yuma and Del Rio — a magistrate may give a first-time offender 10 or 15 days in detention after a guilty plea. The number of defendants seen per day varies, from 20 to 40 in Yuma to 13 to 80 in Del Rio.

Currently, according to federal public defenders working in Del Rio and Yuma, the number of Streamline defendants in court on any given day equals the entirety of the Border Patrol’s most recent “catch” for the sector.

Yet the Tucson sector — which in fiscal year 2009 boasted a whopping 241,673 Border Patrol apprehensions of illegal aliens — cannot implement a zero-tolerance strategy when it comes to immigrant prosecutions.

Lack of resources and the infrastructure of the Tucson courthouse have limited prosecutions to precisely 70 defendants per weekday, or about 7 percent of the average of nearly 1,000 apprehensions each weekday.

In testimony before the U.S. Sentencing Commission in January, Tucson Magistrate Judge Jennifer Guerin reported that since its 2008 implementation in Tucson, about 30,000 people had been prosecuted through Streamline.

(The Border Patrol claims that the total number of Streamline convictions has topped 133,000 since the program’s 2005 launch, but analysts believe this number is low, and the Border Patrol acknowledges that certain sectors are not included.)

Seventy percent of the 30,000 prosecuted in Tucson had no criminal record and were charged with first-time illegal entry and received time served, Guerin says. The other 30 percent were charged with both felony illegal reentry and misdemeanor illegal entry. These “flips,” as lawyers refer to them, pleaded guilty to the lesser charge and received some jail time as part of an agreement with prosecutors.

These percentages are mirrored in the 70 defendants presented at 1:30 p.m. each day in the Tucson court, where the majority are misdemeanors, and the rest are plea bargains.

How does the Border Patrol cherry-pick 70 defendants from the 1,000 people whom agents apprehend each day in the Tucson sector?

Steven Cribby, a Washington, D.C.-based spokesman for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, said the 70 are plucked from those captured in a “target enforcement zone” selected by the Tucson sector chief. Those who meet the Border Patrol’s criteria are referred for prosecution. Those who do not are offered voluntary return to Mexico or processed for removal.

But that explanation fails to account for how the Border Patrol neatly delivers 70 bodies a day to the Tucson court — 30 percent of whom are reentry cases and 70 percent of whom are first-timers.

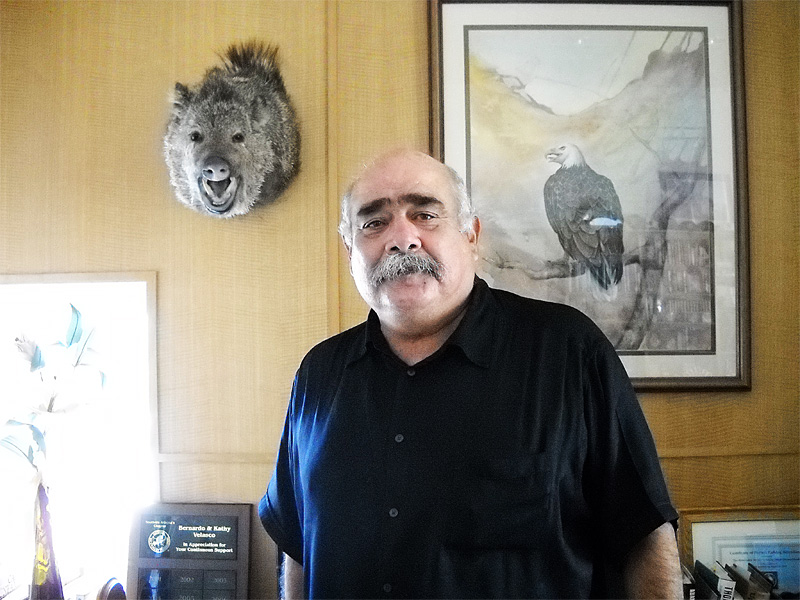

Why not prosecute 70 migrants who have been removed previously? That query makes Magistrate Judge Bernardo Velasco wonder. Velasco is one of the seven federal magistrates in Tucson who hear Streamline cases on a rotating basis.

“[Prosecuting] multiple offenders,” says Velasco, “would seem to suggest that we have limited resources and [that] we’re going to use our limited resources against multiple offenders. That kind of makes sense. But [the Border Patrol] has chosen not to do that. They think prosecuting first offenders is effective.”

Kenneth Quillin, a Border Patrol spokesman in Yuma, says his agency believes Streamline has helped it gain “operational control” over the Yuma sector, because migrants now know there are consequences for crossing illegally.

“I think word got down to would-be crossers,” says Quillin, “that if you were to cross in this area, you’re going to at least, one, get a charge and, two, spend a little time in jail.”

Whether that analysis is accurate, it’s interesting to observe the contrast between the Streamline proceedings in Tucson’s 414,000-square-foot, glass-and-flagstone Evo A. DeConcini U.S. Courthouse and those that transpire in Yuma’s modest, post-office-size federal court.

Although all magistrates handle the Streamline proceedings differently, Judge Velasco may have the speediest judicial delivery among his colleagues.

Indeed, when Velasco’s on the bench in the Special Proceedings Courtroom, where Tucson’s daily Streamline hearings take place, the veteran magistrate burns through 70 defendants in just under 40 minutes.

During that time, he advises them of their rights, takes their pleas, sentences them — anywhere from time served to 180 days in custody — and has them out the door and on their way back to Mexico, to other parts of Latin America, or to a prison run by CCA.

“I wouldn’t say it’s pretty,” says the blunt Velasco after one Streamline hearing. “But I don’t know of anywhere where it says things should be pretty.”

Some Tucson magistrates take an hour and a half or more to get through these en masse hearings. But when Velasco’s running things, defense lawyers joke that they don’t bother to sit down between clients, as they’ll be back up on their feet in no time.

Velasco dispenses with the men and women in his court in seven-person bursts. The defendants before him are dressed in the dirty, sweaty clothes they were captured in, their hands shackled to their waists, their ankles in fetters.

They look weary and morose. They have not had baths or showers after several days in the desert, and the funk from this forced lack of hygiene pervades the courtroom. Indeed, the wall nearest to where the remainder of the defendants are still seated is blackened with the dirt from countless bodies.

Beside each defendant in front of Velasco is a lawyer, often a private attorney hired by the court for $125 an hour under the provisions of the U.S. Criminal Justice Act, which guarantees counsel to the indigent. Some are represented by salaried federal public defenders. Each lawyer has four to six clients in a day’s Streamline lineup.

Velasco runs through a series of questions relayed to each migrant with the rapidity of an auctioneer, mumbling as he goes, head down.

Individually, he asks them compound questions, translated into Spanish by an interpreter and transmitted to them via headphones: Do you understand your rights and waive them to plead guilty? Are you a citizen of Mexico (or Guatemala or El Salvador), and on such-and-such a date near such-and such a town, did you enter the United States illegally?

The answers never vary: “Sí.”

Then he asks them, as a group, whether anyone has coerced them into a plea of guilty. “No,” the chorus replies.

Again, they’re asked, as a group, whether they are pleading guilty voluntarily because they are in fact guilty. The chorus cries, “Sí.”

First-timers receive time served for the petty offense of illegal entry.

Those charged with illegal reentry, a felony, plead guilty to the lesser offense of illegal entry and get anywhere from 30 to 180 days.

In Yuma, Magistrate Judge Jay Irwin plays tortoise to Judge Velasco’s hare. By comparison, Irwin’s courtroom pace is leisurely, almost plodding. On one summer Monday afternoon, the Streamline hearing involves 23 men and takes about an hour and 48 minutes to complete.

There is one lawyer for all 23 men. Federal public defender Matthew Johnson says he’s handled up to 50 defendants by himself in one day.

Compare this with defenders in Tucson, where each lawyer may represent four to six clients at a time.

Defendants are not handcuffed while in the Yuma courtroom, though they do wear leg irons. They remain seated until they are sentenced and taken away by marshals. The court interpreter speaks to each man directly in Spanish. No headphones are required.

Unlike in Tucson, this pool of defendants is not a percentage of the whole, but rather everyone apprehended recently by the Border Patrol in the Yuma sector. Yuma’s apprehensions are nowhere near the levels of the Tucson sector, and never have been. In fiscal year 2009, there were 6,951 apprehensions in the Yuma sector, down about 95 percent from a 2005 high of 138,438.

Irwin advises the group of their rights, patiently details the charges against them, and individually asks each man whether he understands the charges and whether he has any questions.

Irwin takes their guilty pleas, asking each whether he’s pleading voluntarily and whether he is a citizen of the United States. He questions each man on where and how he entered the country — even getting into details of whether he crossed on foot — whether he was with others, and where he intended to go.

Before each man is sentenced, Johnson reads biographical details concerning each defendant into the record. The details, along with Irwin’s inquiries, have the combined effect of humanizing the defendants, making them individuals instead of part of a faceless herd.

One defendant is a bricklayer’s assistant with a family in Mexico who was traveling to Salinas, California, to look for work. Another, named Flores, is a truck driver from Phoenix arrested at a Border Patrol checkpoint. Johnson says Flores had been a resident of Phoenix for 10 years and before that a resident of Los Angeles for 10 years. He was supporting a wife and four American-citizen kids when collared.

Irwin sentences Flores to 20 days. Getting off with time served is a rarity in Irwin’s court. Even first-timers with no criminal records get 10 days in jail before getting booted out of the country.

Later, in his chambers, Irwin says that “most of the time, not all of the time,” he sends defendants to jail for at least a little while.

Surprisingly, two of the 23 defendants before Judge Irwin were heading back to Mexico when the Border Patrol arrested them. Johnson says he’s been seeing more and more of such cases. Shuttles departing from Phoenix and heading for the border at San Luis, Arizona, are either stopped by Border Patrol agents before they make their destination or checked for undocumented aliens once they’ve arrived.

“A good percentage of our clients are arrested heading back into Mexico,” Johnson says. “The Border Patrol and Customs have what they call ‘southbound operations.’

“You hear people complaining that taxpayer dollars are going to arrest these people and to process them,” he says. “But if we’re arresting people that were footsteps away from Mexico, that argument doesn’t carry much weight.”

Border Patrol’s Yuma sector spokesman acknowledged that the agency conducts southbound ops. He says he can’t say how many illegal aliens are apprehended as they are returning to Mexico.

“Well, at one point they entered,” says Quillin, slyly. “So, no, we don’t treat anybody different. When we approach individuals, and they say they’re going back to Mexico, we just make sure that they do.”

But Johnson ascribes a more insidious Border Patrol motive to its agents busting shuttles headed for Mexico.

“They’re boosting [the Border Patrol’s apprehension] numbers,” says Johnson, “by arresting the people going southbound.”

One final oddity of the Yuma court: During Streamline hearings, a Border Patrol agent plays the part of prosecutor instead of an assistant U.S. Attorney, as in Tucson. Quillin confirms that this person is not a Border Patrol lawyer, simply an agent.

The official line is that this is allowed because the agent isn’t acting as an advocate, but is simply relaying information about the defendant’s criminal or removal history.

Still, Professor Erin Murphy of New York University’s School of Law finds the issue troubling, as she does many aspects of Operation Streamline.

“These are the kinds of shortcuts that should really raise questions,” says Murphy, whose areas of expertise include criminal law and criminal procedure. “I think there are real questions of prosecutorial independence when . . . the police become the prosecutors.”

Streamline’s detractors, including Murphy, point to a number of other legal shortcuts that raise red flags about the constitutionality of the program.

Most troubling for faultfinders are the hearings themselves, which hasten and compress the process of meeting a lawyer for the first time, having an initial appearance before a judge, pleading guilty, and getting sentenced. All this happens in less than a day.

As described, this “streamlined” hearing is performed en masse. Critics charge that such mass proceedings violate defendants’ due-process rights, due process being the underlying concept of fairness that is one of the pillars of our legal system. It’s a concept that dates back to the Magna Carta and is enshrined in the Fifth and 14th amendments.

The Fifth Amendment declares that “no person” shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The 14th Amendment contains the same guarantee, applying it to states.

Although illegal immigrants don’t enjoy all the same rights as citizens, certain basic constitutional protections apply to them, too, particularly during criminal proceedings. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that the due-process clauses of the Constitution’s Fifth and 14th amendments cover “all persons within the United States,” regardless of immigration status.

Though there are pending lawsuits involving Streamline, the courts have yet to address the underlying constitutional questions of whether Streamline defendants are denied due process.

However, in December 2009, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found in U.S. vs. Roblero-Solis that Streamline hearings violated Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which states that judges “must address the defendant personally in open court” and determine whether the defendant’s guilty plea and waiver of rights is voluntary.

“We act within a system maintained by rules of procedure,” Ninth Circuit Judge John Noonan observed in the court’s decision. “We cannot dispense with the rules without setting a precedent subversive of the structure.”

The Ninth Circuit did not tackle constitutional issues, leaving it up to magistrates as to how they should proceed. Nevertheless, the Ninth Circuit made clear that it frowned upon magistrates taking pleas en masse, which was occurring prior to Roblero-Solis.

“To be specific,” Noonan wrote, “no judge, however alert, could tell whether every single person in a group of 47 or 50 affirmatively answered their questions.”

And yet, these en masse hearings continue. And though Tucson magistrates now take pleas individually, some questions are still asked of 70 people at a time or of smaller groups of seven at a time.

Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional scholar and dean of the University of California-Irvine School of Law, was shocked when the operation of Judge Velasco’s court was described to him.

“Seventy individuals in 40 minutes is about 30 seconds per,” says Chemerinsky. “I haven’t seen it — I don’t want to offer any conclusions — but I am skeptical that you can, in 30 seconds, give someone a meaningful hearing.”

However, during an interview for this article, District of Arizona Chief Judge John Roll defended the way Streamline cases are handled in the state.

“If I thought that due process suffered,” he insists, “I certainly would oppose it. But I don’t think that is the situation.”

He points out that defendants in Streamline have waived their rights to an individual hearing and to a trial.

“Most of the individuals prefer [Streamline],” he says, “because it means they’re going to have their cases resolved speedily.”

Therein lies the rub, insist Streamline’s disparagers. Defendants have to knowingly and willingly waive their rights. But with Streamline, defendants have little choice. Demanding a trial would mean a month or more in custody awaiting a trial date, far more time than a day or two of time served.

It’s no wonder, then, that 99 percent of all Streamline defendants plead guilty. Individual plea hearings or actual trials are rarities.

Roll’s rationale for the program doesn’t impress Professor Murphy.

“It strikes me as sad,” she says, “that the defense of a system that cannot afford to give every person the justice they’re entitled is that, ‘Well, at least this is faster.’

“That just points to the fundamental problem,” she says. “If the system cannot accommodate the volume it seeks . . . without fundamentally compromising the principles that make the system fair to begin with, then . . . something is wrong.”

Actually, the Border Patrol would like to double or triple the number of Streamline defendants. And there have been discussions about increasing the total to at least 100 a day in Tucson.

Murphy and others assert that Streamline defendants are not knowingly and intelligently waiving their rights. Similarly, the defendants’ Sixth Amendment right to counsel suffers from the Streamline process, they contend.

Indeed, several federal public defenders interviewed express doubts that their Streamline clients are receiving the legal representation they need.

Juan Rocha is one. He’s worked in both the Yuma and the Tucson courthouses on Streamline cases, and he says, particularly in Tucson’s factory-like churn, he feels helpless to assist Streamline defendants.

“In Tucson, you’re basically shepherding people to prison or to deportation proceedings,” he says. “Because you’re not really doing much for them.”

William Fry, federal public defender supervisor in Del Rio, says the number of Streamline defendants in the Texas court fluctuates, from a low of 13 to 20 a day to a high of 80 to 110.

Because his lawyers get to interview their clients only the day before they go in front of a judge, there’s little time to research the prosecution’s claims against the defendant or to suss out possible citizenship claims.

“The defense lawyer in many ways has to buy a pig in a poke,” Fry says. “We have to take at face value what the government says it’s got on this guy when we make our decisions. And we only have a day to do it in.”

In Tucson and Yuma, defense attorneys have even less time, as they meet Streamline clients on the morning of their hearings. In Tucson, lawyers can consult with their clients one-on-one. In Yuma, federal public defenders may have to address defendants in groups of four to six.

Rocha says he knew of several cases in Yuma in which the Border Patrol had, at one point, U.S. citizens in custody, ready to be presented to the Streamline judge.

Once someone is identified as a citizen, the Streamline charges can be dismissed. But determining citizenship can be complex and time-consuming. In fact, defendants may not be aware that they have a citizenship claim.

And there are other problems that arise when a lawyer doesn’t get to spend enough time with a client.

For instance, charges against juveniles, those not competent to stand trial, or others who speak indigenous languages, rather than Spanish or English, are supposed to be dismissed by the prosecutor, according to an understanding between federal attorneys and defense lawyers in Streamline.

Heather Williams, a supervisor in the Tucson public defender’s office and one of Streamline’s most outspoken critics, says this does not always happen. The very nature of the mass proceedings and the speed with which they occur do not allow defense attorneys time to investigate each case thoroughly.

“We find people who turn out to be juveniles,” she says in her office near DeConcini Courthouse. “There’s a whole other proceeding that’s supposed to happen if somebody’s a juvenile in federal court charged with a crime. And we find out after the fact.”

Because of the language gap (some defendants even speak indigenous languages such as Mixtec or Olmec), Williams says her office sometimes learns afterward that a client had no idea of what was going on during a Streamline hearing.

She asserts that in post-conviction conversations with clients, public defenders may discover that defendants were not competent to go through the hearing and waive their rights.

Williams decries what she sees as the inhumanity of Streamline’s conveyor-belt approach to justice. She bemoans the shackles and the leg irons each defendant must wear.

“They are truly being treated like cattle,” she says.

The U.S. Marshals Service counters that all defendants in the Tucson court, Streamline and non-Streamline, are so restrained. The marshals cite crowding issues in the court, which operates at or over capacity.

Certainly, Streamline defendants are not known to be aggressive. But with three or four marshals in the Streamline court operating with three Border Patrol agents as backup, if all 70 defendants were unrestrained and wanted to pull a reenactment of the Spartacus uprising, the marshals and BP agents could be overwhelmed.

“It creates a huge, huge security risk to have them unrestrained,” says Assistant Chief Deputy Marshal Ray Kondo, in charge of security for the Tucson court. “The only time they’re not [restrained] is in a trial, because it would be prejudicial in front of a jury.”

Yet it is unnerving to see 70 Latinos — whose main crime is wanting to come here to work — shuffling about in restraints befitting a serial killer.

Williams can recall more disturbing scenes — Streamline cases in which defendants had been in rollover accidents before they were apprehended. Some were paralyzed, but arrangements were made for their initial appearances to occur from their hospital beds, she says.

“We’ve actually had instances where Border Patrol has shot somebody,” she says, “and the person has been brought into court a day or so later, fresh from the hospital, having had surgery and having been totally out of it.”

There are also concerns about clients having TB, MRSA, bacterial meningitis, and H1N1. But because they are in custody for such a short periods, they often cannot be tested, isolated, or diagnosed. Williams says her office sometimes learns that the courtroom may have been exposed to disease after the fact.

More worrisome for constitutional sticklers such as Murphy is that by condoning Streamline’s mass hearings, the criminal justice system is creating a dangerous precedent.

“There’s the canary-in-the-coal-mine scenario,” says Murphy. “The line between immigrants and citizens [becomes] much more porous.”

At least one Streamline defense attorney offers a cynical appraisal of due-process concerns. Dan Anderson, who reps Streamline clients in Tucson a couple of days each week, calls the due-process standard in Streamline, “Your cheeseburger, no-frills, American due process.”

Regarding Streamline’s critics, he offers a jaundiced appraisal, noting that it’s not just Streamline defendants who have due-process issues.

“I understand the hue and cry about due process,” Anderson says. “But as far as I can tell, those same voices are deafeningly silent when some homeless vet pleads guilty without the advice of counsel and gets 30 days in jail for sleeping in a public park or [urinating] on a dumpster behind the Circle K.”

Beyond the constitutional and humanitarian concerns voiced by Streamline’s opponents, Streamline’s cost and inefficiency call the effort into serious question, as well.

Streamline itself does not have a budget. Instead, the program pulls from the resources of the various agencies involved — U.S. Attorneys, Marshals, and federal public defenders offices, Border Patrol, and the federal judiciary.

Putting a price tag on Streamline is difficult, so difficult that even Streamline’s most enthusiastic cheerleaders have no idea of the program’s overall cost.

However, there are estimates of certain specific costs associated with Streamline in Tucson.

In a report published by the University of California-Berkeley Law School’s Warren Institute on Race, Ethnicity, and Diversity, titled Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline, researcher Joanna Lydgate estimated that it costs DHS $52.5 million annually to detain Streamline defendants in Tucson, at a rate of $100 per person per day.

Lydgate was asked by congressional staffers to estimate the cost of fully funding Streamline in Tucson, if the program were to be zero-tolerance and hit every border crosser apprehended with a criminal charge. She and other Warren Institute researchers suggested that zero-tolerance in Tucson could cost $1 billion a year.

This may not be far from the mark. Chief Judge Roll estimates that doubling the number of Streamline defendants in Tucson could cost $18 million more a year. That would be in addition to the $5 million per year that Tucson’s Streamline court now costs, according to Roll’s estimate.

Tripling the number of Tucson defendants in Streamline could cost $27 million more. These are court costs alone, says Roll, and do not include “marshal or prosecutorial expenses.”

Tripling Streamline’s defendants would get the Border Patrol nowhere near zero tolerance. That would require about 1,000 prosecutions per weekday in Tucson, on average.

Federal public defender Williams estimates that for fiscal year 2010, the cost of attorney fees — including those of both public defenders and outside attorneys — will top $3.6 million. If the court began processing twice as many defendants a day, as has been proposed, the bill would rise to $6.3 million a year.

U.S. Marshal for Arizona David Gonzales says he writes a $13 million check each month to private jails giant Corrections Corporation of America for the incarceration of federal prisoners in Arizona. Gonzales says about 75 percent of this covers the cost of prisoners with immigration-related offenses, like those in Streamline.

In August, President Obama signed a $600 million supplemental border-security package, from which many of the stakeholders in Streamline received a chunk, from $254 million for Customs and Border Protection to $196 million for the Department of Justice.

Presumably, some of the additional money would assist in the prosecution of Streamline cases. But when Republican U.S. Senator John McCain sought an additional $200 million for Streamline during Senate debate over the bill, New York Democrat Charles Schumer shot it down.

“Operation Streamline is, first, expensive,” Schumer told his colleague. “And if you’re going to immediately incarcerate everyone who’s apprehended at the border, you pay for their healthcare, you pay for their food. It’s over $100 a day [per person to jail them].”

Nevertheless, McCain and Arizona’s junior senator, Jon Kyl, have made fully funding Streamline point number two in their 10-point “Border Security Action Plan.” McCain and Kyl bring up Streamline every chance they get — during U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder’s confirmation hearing, for instance, and during Arizona U.S. Attorney Dennis Burke’s appearances before Senate committees.

During one of the appearances, Burke suggested the impact of Streamline on his office, stating that it filed 22,000 misdemeanor immigration cases and 3,200 immigration felony cases in fiscal 2009. It’s safe to presume that most, if not all, of the misdemeanor cases were from Operation Streamline.

McCain and Kyl claim that they believe Streamline works and want to give the program the resources it needs. This while Democrats such as Schumer acknowledge problems with Streamline yet allow the program to operate.

The Border Patrol’s claims to the contrary, there’s little evidence that Operation Streamline is a deterrent. For instance, Border Patrol numbers have shown a 75 percent decline in apprehensions in the Del Rio sector since Streamline began there in 2005. But from 2000 through 2004 — before Streamline was in place — apprehensions in the Del Rio sector declined by 65 percent.

Lydgate’s study for the Warren Institute eviscerated Streamline’s efficacy as a deterrent, observing that large fluctuations in Border Patrol apprehensions preceded Streamline’s implementation.

“The general decline in border apprehensions,” Lydgate wrote, “did not begin in 2005 — when [Homeland Security] introduced Operation Streamline — but in 2000. Apprehensions reached a decade peak in 2000, then steadily decreased ’til 2003, went up slightly in 2004 and 2005, and decreased again between 2005 and 2008.”

The Border Patrol’s assertions of Streamline’s success rely upon a logical fallacy, one that assumes Streamline has caused the decline in apprehensions, even when there are more powerful factors at play — including the economic downturn. Lydgate’s study, for instance, offers a chart showing that “border apprehensions have largely [mirrored fluctuations in] the U.S. job market since 1991.”

A supplemental study by Lydgate analyzed border enforcement in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of California, which does not participate in Operation Streamline.

She found that from 2008 to 2009, apprehensions declined by about 25 percent in that district, observing that this “indicates that declining apprehensions in other border sectors . . . are likely not a result of Operation Streamline.”

Lydgate reported that the Southern District of California generally does not prosecute first-time border crossers, focusing instead on “crossers it believes are most likely to cause violence.”

Yet the Southern District of California ranks “first nationwide in per capita prosecutions of alien smuggling . . . and importing controlled substances,” according to Lydgate.

Also, the Border Patrol claims a 12 percent recidivism rate for Streamline. But critics object, saying a realistic recidivism rate cannot be determined when the Border Patrol cannot estimate how many migrants elude capture.

“From the perspective of defense attorneys,” Lydgate tells New Times, “they do see people who come back again. There’s no doubt that that happens.”

Both judges, Irwin and Velasco, acknowledge seeing Streamline defendants return to their courts. And as has already been discussed, 30 percent of the convictions in the Tucson version of Streamline involve people charged with felony reentry. Even if this number is artificially manipulated by Border Patrol, it suggests that recidivism is higher than 12 percent.

Lydgate contends Streamline is a drain on resources that could otherwise be used to fight more serious criminal activity. And there’s substantial evidence that Streamline has overtaxed the criminal justice system.

Judge Roll, for instance, says the Tucson court is basically running at capacity and doesn’t have the space to increase even to the 100 cases a day the Border Patrol would like to see.

“We have absolutely no free space in the DeConcini courthouse in Tucson,” Roll says. “All courtrooms are fully utilized.”

Assistant Chief Deputy Marshal Kondo likened the moving of prisoners through the courthouse to choreographing a ballet. The capacity of the courthouse’s small cell block is rated at anywhere from 88 to 102. But Kondo regularly is dealing with 250-plus prisoners who go through that cell block each day.

Kondo’s boss, U.S. Marshal Gonzales, says marshals already have a full plate.

“If it was just Streamline,” Gonzales says, “if that’s all we had to deal with, it wouldn’t be a problem.”

That is, Streamline requires a certain number of Gonzales’ men a day. Those are men who could be doing more important work — including chasing escaped fugitives.

Streamline’s strain is felt beyond Arizona. Lydgate asserts that prosecutions of “petty immigration-related offenses” have skyrocketed 330 percent in border courts from 2002 to 2008.

The Berkeley law school researcher quotes a 2008 report from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts as stating:

“There are simply not enough jail beds, holding cells, courtrooms, and related court facilities along the border to handle all the cases that the government would like to prosecute under [Operation Streamline].”

In 2008 testimony before the U.S. House Subcommittee of Commercial and Administrative Law, federal public defender supervisor Williams summed up Operation Streamline in words that still ring true.

“Operation Streamline,” she said, “may well be one of the least successful, but most costly and time consuming ways of discouraging [illegal] entries and reentries.”

Similarly, Lydgate points out that hunger and life-or-death necessity trump any deterrent effect caused by a possible criminal sanction.

“Streamline is just not going to deter someone who needs to find work,” Lydgate says. “Some people will come back again and again, even if they understand they may be prosecuted again.”

If Williams and Lydgate are correct, why does the Obama administration continue to back this pricey policy lemon?

Perhaps there are simply too many who profit from Streamline.

Certainly, the Border Patrol benefits from this rationale for its increasingly bloated budget — nearly $3.6 billion for fiscal year 2010, with 4,290 Border Patrol agents in Arizona and more than 20,000 agents nationwide.

In addition, the $600 million supplemental border-security package recently signed by President Obama will add 1,000 Border Patrol agents and 500 customs officers to the southwest border. They will be assisted by the 1,200 National Guard troops deployed by the Obama administration to the region. Nearly half of the troops will be stationed in Arizona.

Also, private prisons profit off the creation of newly minted “criminal aliens,” with the U.S. Marshal for Arizona now shelling out $13 million a month — potentially $156 million a year — to Corrections Corporation of America to hold federal prisoners in Florence, Arizona.

Anyone visiting Tucson will see the ubiquitous Wackenhut buses ferrying undocumented immigrants to and from the federal courthouse. The Border Patrol has contracted with the global security firm Wackenhut/G4S since 2006 to provide transportation for the migrants the Border Patrol captures.

According to Wackenhut/G4S’s own Web site, it employs more than 600 “officers” operating more than 100 buses and vans along the U.S.-Mexico Border. The current CBP-Wackenhut contract is worth about $76 million a year.

It’s not just the “prison industrial complex” (as some immigrant-rights activists refer to it) that benefits. It’s the economies of the cities where Streamline is active.

“It’s a job stimulus,” says Judge Velasco. “It’s tremendous for employment for law enforcement, lawyers, marshals, private citizens running private prisons. These policies generate a lot of money. There’s a lot of people living well on the war on drugs and aliens.”

Other than the money to be made and the jobs boon from Streamline, there’s another calculus to bear in mind: the human suffering of otherwise ordinary people labeled and processed as common criminals.

“This is the least-known part of the militarization of the border,” say Pima County legal defender Isabel Garcia, a pro-immigrant firebrand well known from her appearances on CNN.

“Somebody’s making money,” she adds. “That’s what I believe this is all about. But, secondly, right with it is to criminalize people. Criminalize in the real sense of the word . . . When you criminalize it with a case, [immigrants] will not be able to come back to the U.S. [legally].”

That criminalization is brought full-circle when deportees are dropped off at the DeConcini port of entry, the main gateway between the U.S. and Mexican sides of Nogales.

The port of entry is the namesake of former U.S. Senator from Arizona Dennis DeConcini, son of the late Arizona Supreme Court Justice Evo DeConcini, whom the Tucson courthouse is named after.

Ironically, Dennis DeConcini is on the board of directors of Corrections Corporation of America, which owes part of its vast wealth to the Streamline hearings in Tucson.

From the DeConcini port of entry, or the Mariposa port of entry on the other side of town, migrants make their way to one of a network of private and governmental social-service agencies, where they can get fed, find a place to stay, and catch a cheap bus back to their hometowns.

Spouses caught together on the U.S. side often are separated during the Streamline process. At the Grupos Beta aid station in Nogales, husbands look for their wives, wives seek their husbands.

Their search may be made more difficult because many immigrants do not get their possessions back from the Border Patrol, which confiscates personal property upon arrest. Such personal property could include money, vital identification, cell phones, contact numbers, and addresses of loved ones.

Also, people are sometimes dropped off at ports of entry far from where they crossed, even in different states, such as California. And the Border Patrol has partnered in the past with other federal agencies to repatriate some migrants by flying them by the planeload to Mexico City, far from the border. That program costs the United States $15 million a year.

In Tucson there have been instances of wives in Streamline court asking for more time so that they can be released the same day as their husbands. Magistrates sometimes reluctantly grant such requests.

On one hot Saturday afternoon at the Grupos Beta station, a slight young man on the verge of tears comes forward to relate his Streamline experience.

The man had been crossing with his wife, five months pregnant, when they were both arrested by the Border Patrol. They’d been heading for Salinas, where they’d hoped to find work in the fields.

He saw her after their capture, but they were separated when he went to court before Judge Velasco, who gave him time served after he pleaded guilty to illegal entry. He had no idea where his wife was, whether she was safe, or whether their first child together was still well in her womb.

After court, the man asked Border Patrol agents what happened to his wife. All they would tell him was that she already had left.

He has a photo of his wife, a pretty woman with indigenous features. No one at Grupos Beta has seen her yet. He says they’re both from Oaxaca. He seems utterly helpless, distraught.

Complicating matters was the fact that his wife gave the Border Patrol a different name. The Tucson-based human-rights group Derechos Humanos later attempted to locate her, with no luck.

And by that time, they had lost contact with the husband, as well.

Chalk up two more lives upended in the pitiless mechanism known as Streamline.

Operation Streamline’s a mega-expensive quagmire that fattens the U.S. Border Patrol’s budget and enriches private corporations. It diverts resources from pursuing serious crimes, such as human smuggling and drug and gun trafficking.

Streamline’s critics complain that the program’s arbitrary and inhumane, violating due-process and effective-use-of-counsel requirements of the U.S. Constitution.

Anti-migrant zealots want every apprehended undocumented alien processed and removed through Streamline’s en masse court proceedings. It’s estimated that this would cost a billion dollars a year in the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector alone.