W. may be less frenzied than the usual Oliver Stone sensory bombardment, but in revisiting the early ’00s by way of the late ’60s, this psycho-historical portrait of George W. Bush has all the queasy appeal of a strychnine-laced acid flashback. Hideous re-creations of the shock-and-awful recent past merge with extravagant lowlights from the formative years and early career of America’s most disastrous president (crudely played by Josh Brolin, often in tight close-up). Familiar faces seem to deliquesce before our eyes. It’s unavoidably trippy, but does anyone, other than the perpetrators, really need to relive this particular purple haze?

W., which is as much edited as it is directed, with a script by Stone buddy Stanley Weiser, has a patchwork chronology that takes as its central pattern the run-up to the Iraq War and the ensuing search for the missing weapons of mass destruction, while pushing two theses regarding the nature of its eponymous antihero.

The more heavy-handed of these dramatizes Dubya’s tormented relationship, alternately worshipful and rebellious, with his disapproving father (James Cromwell). “What do you think you are—a Kennedy?” Poppy thunders when confronted with his wastrel son’s latest drunken indiscretion. “You’re a Bush!” It’s the Oedipal saga that Maureen Dowd, for one, began recounting during the 2000 election, which reached its climax when the son corrected his father’s error by deposing Saddam Hussein.

In this scenario, the younger Bush became president to take revenge on the elder. Stone has Dubya watching the 1992 election returns with his family. As defeated Poppy chokes back tears, Dubya trumps even the bilious, class-fueled anti-Clinton rage expressed by mother Barbara (Ellen Burstyn) in ranting about H.W.’s failure to go all the way to Baghdad. This W. is the saga of a tormented, father-obsessed asshole who manages to play out his family drama on a world-historical stage.

The second thesis—implicit in Kevin Phillips’ chronicle of the Bush family’s ascent, American Dynasty, and developed elsewhere—credits Dubya with a powerful insight into American politics. Having checked his alcoholism with a regimen of fundamentalist Bible study and consequently served as Poppy’s liaison to the Christian right, the younger Bush assimilated Christian values rhetoric and successfully organized an evangelical base which would enable him to pulverize John McCain in the 2000 primaries and win re-election in 2004.

Although W. dramatizes neither of these campaigns—generally eschewing the public Bush in favor of his assumed backstage persona—Stone and Weiser go so far as to cast Lee Atwater as their antihero, suggesting that it was his canny appreciation for dirty tricks that got Poppy elected in 1988, years before self-identified “fairy” Karl Rove taught him his political catechism. But undermining his own theory, Stone presents Dubya as an idiot savant who believes his own bullshit, warning Poppy that too much thinking screws up the mind and bragging that he’s decided to run for president because God told him to.

Although personality regularly trumps political process in the world of Oliver Stone, W. seems most deeply concerned with the run-up to the Iraq war, thus working the same territory as David Hare’s play, Stuff Happens. Each given a presidential nickname to wear like a baseball cap, Bush’s enablers—Dick “Vice” Cheney (Richard Dreyfuss, having evident fun), Donald “Rummy” Rumsfeld (Scott Glenn), Condi “Girl” Rice (Thandie Newton, looking as though she’s going to gag), Karl “Boy Genius” Rove (Toby Jones), and “Brother” George Tenet (Bruce McGill)—confound the cautious and rational Colin “Colin” Powell (Jeffrey Wright) to lead the republic toward disaster.

Not fair (not a problem) and definitely not balanced: The least-nuanced performance in a film full of cartoon characterizations is Brolin’s Bush. A simian slob modeled on Andy Griffith’s raucous run-amok in A Face in the Crowd and given to bad-tempered pronouncements while stuffing his face, Brolin uses stupidity as a crucifix. He wards off sympathy as though it were a vampire. In directing Brolin, Stone is disinclined to give the devil his due. Bush’s mean-spirited charm is nowhere evident—despite the devotion he inspires in wife Laura. What exactly is this sweet young hottie (Elizabeth Banks) supposed to see in him?

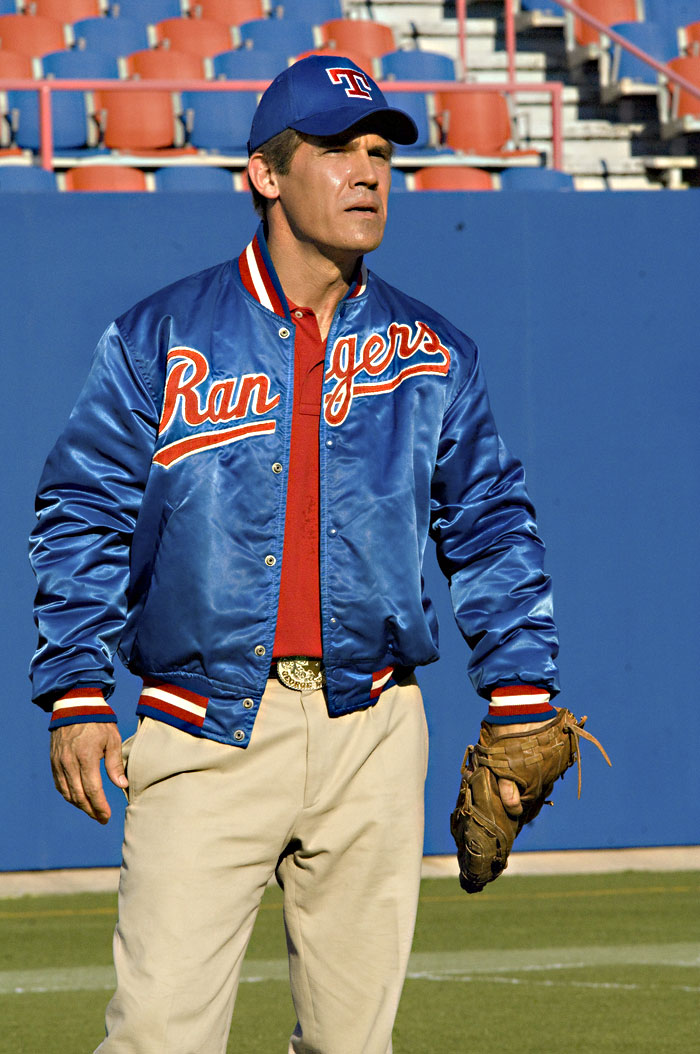

What are we? W. can’t decide whether its aspirations are Shakespearean tragedy, political critique, or cathartic black comedy. The emotionally reductive Stone really only had a shot at the latter. At its best, W. suggests Stuff Happens reconfigured for the cast of Saturday Night Live. Running through Bush’s greatest bits—choking on a potato chip, confusing Guantánamo with “Guantanamera,” calling himself “the decider,” complaining that he’s always been misunderestimated by Saddam Hussein—W. begs the question posed by its two theses. Like how did this stunted creature, who considers his greatest mistake to have been trading Sammy Sosa from the Texas Rangers, become our king? (The fault, I’m afraid, lies not in our stars…)

Released early in the 1992 campaign, JFK did its modest part to destabilize the first Bush’s Republican nation and contribute to Bill Clinton’s Kennedy-identified juggernaut. To the degree that W. is able to make itself present in the hurly-burly of the election’s final weeks, it should prove mildly helpful to the Democrats. Cable news won’t be able to resist the movie’s most outrageous scenes, and such blatant Bush bludgeoning should compel a few Republican pols and right-wing pundits to rise to their maligned leader’s defense.

Many more people will see W.‘s choice moments as de facto campaign ads on TV or YouTube than will ever sit through the movie. W. may be opening at a good time, but it doesn’t exactly promise one. Stone omits the stolen 2000 election, stops short of the 2004 campaign, and spares us the second term, but this is still a painful movie to endure. I blame history more than Stone for that—it’s a shame that four years ago, when the filmmaker contemplated the nature of imperial hubris, the gods decreed he should unleash Alexander rather than this. Back then, W. might actually have made a difference.