The visual-arts component of Bumbershoot can be hard to find, since the indoor venues vary from year to year. Over at the Seattle Center Pavilion, next to the skate park, are three attractions. Just down the stairs to Fisher Pavilion, facing the TuneIn Stage on the lawn, are another four. (The Flatstock poster exhibition has been kicked out of Fisher Pavilion in favor of the Armory.) I’ll file three dispatches from Bumbershoots on the seven galleries, which are hit and miss. The good news is that they’re all so close together in the southwest corner of the Bumber-grounds; if you don’t like one thing, it’s a short walk to the next. My favorite installation, by Brooklyn artist Jonathan Schipper, is worth visiting all three days of the festival, since it’s growing over the weekend, starting with road salt and a laptop.

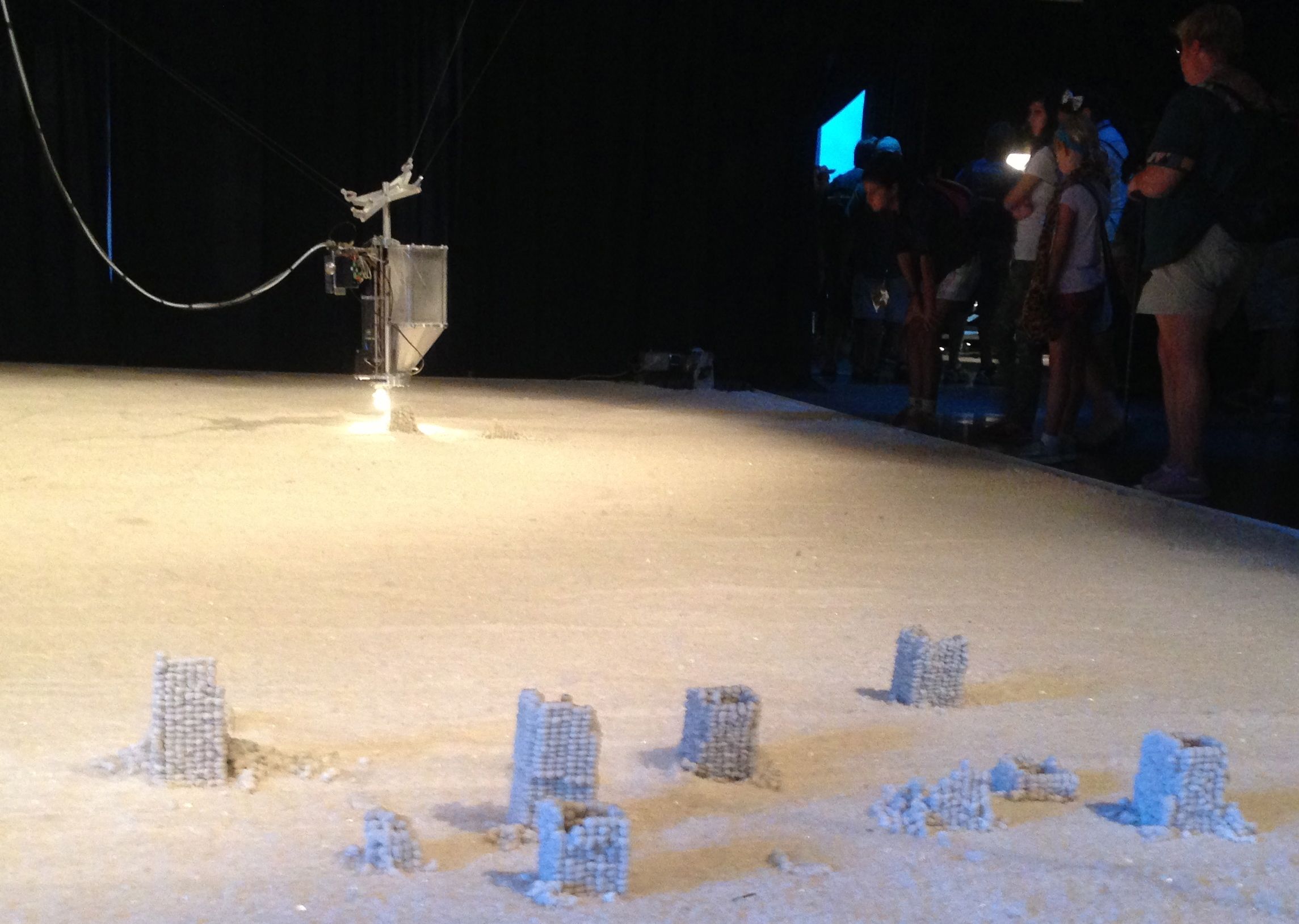

In Fisher Pavilion, the California native Schipper has two large mechanical works on view in detritus we value: an older kinetic sculpture called Measuring Angst (more on that below); and the new Detritus, a 30-foot by 30-foot field of salt with a strange, cable-controlled hopper dangling overhead, its movements guided by a laptop running 3-D printer software. If you’ve ever seen an NFL game with one of those cameras dangling over the stadium, the salt hopper operates somewhat the same way, with four cables spooling in each corner of the field, reeling it this way and that.

The hovering hopper is like the stylus of a pen, extruding water, heat, and salt, which congeals into little balls, which are the basic building units of what appears to be sprouting like a miniature city of salt in the desert. “This is the first time we’ve shown it,” says Schipper, a tall, friendly, bearded fellow who also made his own eyeglasses with a 3-D printer. “It’s not a set design,” he says of the programming instructions; he and his assistants can modify Detritus during its inaugural performance so that, from a few isolated towers (on Saturday afternoon) the piece will over the next two days “grow from a town into a small city.”

It’s a city like a small model diorama at 1/32 scale, and the expanse of salt is also reminiscent of a Japanese rock garden. Kids and parents are drawn to the thing: There’s both a Zen effect and a cool mechanical contraption to watch. (It requires refilling every hour or so, says Schipper, when the hopper retreats to the corner like a boxer between rounds.) When I entered Fisher Pavilion, I counted four little outposts; by the time I left, fifth colony had emerged. And the sculpture, with a bit of human help, feeds upon itself. “That’s three tons of salt,” Schipper explains. After his city is built Sunday night, it’ll be ground back into its original firm, then returned to WSDOT or SDOT or whoever uses road salt these days. In that way, too, Detritus will be like a sand mandala: carefully built but ephemeral. “A lot of art is a destructive process,” says Schipper, not sounding too concerned about the fate of the piece, which he sees as a kind of analogue to “imagining humanity building stuff and watching it erode.” It’s a prelude to a larger project planned in New York that will employ the same technology over three or four months, he explains, filling a much larger space with much more salt.

Pictured above (and see better photos on Schipper’s website, oppositionart.com), Measuring Angst is also programmed with 3-D printing software as hydraulic arms systematically and very slowly shatter a bottle of Corona beer, then reassemble it again. (The whole cycle takes about eight minutes.) It’s based on the angry gesture of hurling a bottle toward a wall, Schipper explains, here rendered as a hyper-slo-motion mechanical ballet. It doesn’t have the scale of Detritus, but it’s more robot-y, vaguely suggesting a space station floating in the gallery.