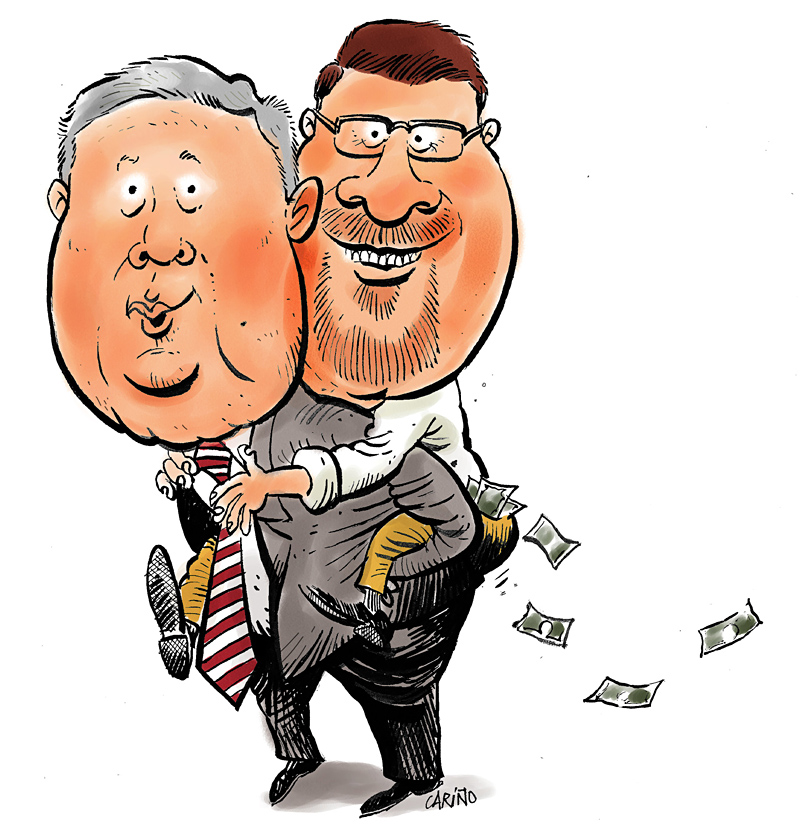

It had to do with family, Norm Dicks said in announcing last week that he will retire after his current 18th term as the “congressman from Boeing.” The “top appropriator,” a position that benefited him politically and familially, says he and wife Suzie “have made the decision to change gears and enjoy life at a different pace.” Yet his statement, and most media coverage of it, made no mention of another family member who might have influenced his surprise announcement.

In 2007, Dicks took over as chair of the House Interior Subcommittee just months before his son David became head of the Puget Sound Partnership, a newly created public/private state agency designated to help clean up Sound pollution, but one that lacked any significant funding. David, who told interviewers he was certain he could get the necessary money to run and expand the agency, had been appointed to the post by Gov. Chris Gregoire, who refers to his father as “a trusted partner, a staunch ally, and a close friend.”

David Dicks’ agency initially received $500,000 funding from the Environmental Protection Agency, as KUOW reported in a series of stories by John Ryan questioning the operation’s finances. But, as Rep. Dicks would later boast in 2010, “Since then, we’ve put in $93 million for Puget Sound cleanup in the federal legislation,” millions of it going directly to his son’s project.

To some it seemed a conflict of interest for a father to direct public funds to an agency where his son earned $129,000 a year as an administrator. Furthermore, some of those funds were mismanaged, said a May 2010 report by Washington State Auditor Brian Sonntag. The younger Dicks’ operation intentionally ignored state financial policies, said Sonntag, and its errant spending practices “went beyond sloppy bookkeeping.”

In one instance, David hired prominent Seattle attorney Gerry Johnson, a longtime friend of and political contributor to his father, at up to $478 an hour to work with the Partnership. To avoid putting the legal work out for public bid by other firms, young Dicks’ agency signed Johnson’s firm, K&L Gates, to a $19,999 contract—$1 under the ceiling for must-bid contractors. The agency then later rewrote the contract several times until it was increased to more than $51,000.

In the wake of the audit revelations, David quit the post in 2010—about the time his father lost the Interior chair (Republicans had just won control of the House). Young Dicks then found another state job, beating more than 70 applicants for a $75,000 part-time directorship at the University of Washington’s College of the Environment.

But the father/son funding issue kept resurfacing last year as questions lingered about the ethics of such an arrangement. A few weeks ago, it cropped up again, raising more questions.

As The Washington Post reported one month ago, the 6th District congressman originally secured a $1.82 million earmark for the Partnership and more than $14 million in grants and other funds that also went to his son’s agency. There were no competitors for the funds. Said the Post: “The earmark and grants are unreported elements in the story of the father and son and Puget Sound, which has long been controversial in the Pacific Northwest, spawning charges of nepotism, waste, and no-bid contracts, according to state audits and political opponents . . . The case illustrates the complications that can arise when a lawmaker’s congressional actions benefit not only his district but also a family member.”

Dicks told the Post he still sees no problem with giving his son’s agency wads of taxpayer funds. “I don’t think there was a conflict,” he said. “David got the job through a competitive process . . . he had the passion for the job.” David, 40, told the Post his father “didn’t do it for me; he did it because he cares about Puget Sound and he finally had the ability to do something about it.”

Norm Dicks later called the Post story unfair, and said no one has come forward to demand he stop funding the cleanup of Puget Sound, as if that were the issue. But no one can convince Stormin’ Norman or his supporters that he was doing anything wrong. He’s the congressman most able to bring home the regional pork, even if some does go to his family. Norm’s Army agrees with him: If he doesn’t snap up the funds, some other politician will.

That was the mantra of Dicks’ mentor, Sen. Warren Magnuson, remembered for adding an innocent line to an appropriations bill—and Grand Coulee Dam was born. Dicks became almost as legendary. A 2010 study showed how defense contractors and other recipients of federal earmarks (a money-gifting habit that Dicks says he’s since given up) returned favors to him and other legislators, mostly in the form of weighty campaign contributions. Those donations helped Dicks walk rather than run for re-election every two years, almost automatically returning him to a job that pays $174,000 annually, not counting perks and health-care benefits, topped off afterward by a $60,000 annual retirement check.

As Magnuson used to say, and Dicks always preached: “What do they want me to do, send the money to New Jersey?” Well, not necessarily. But last week the 71-year-old congressman may finally have tired of people wondering whether he had to send it to admirers and family, too.