A quick scan of Seattle’s independent cinema scene might leave you thinking the neighborhood theater is on its last reel. Queen Anne’s Uptown closed before Thanksgiving. The U District’s Neptune is evolving into a music venue, swapping matinees for mini-skirts. And in December, Paul Doyle, CEO of the cash-strapped Columbia City Cinema, was busted for violating the Washington Securities Act after financial authorities alleged he was trying to sell stock in the struggling theater through Facebook.

Call it the Curse of Netflix. It’s never been easier—not to mention cheaper—to watch movies at home. And in the Great Recession, there’s even less incentive to put on pants and brave the rain when the endgame is being gouged for a $6 bucket of oversalted, underbuttered popcorn.

It’s a curse known well to Jeff Brein. As managing partner of Far Away Entertainment, a chain of eight local theaters, Brein has recently experienced the gut punch that is downsizing after the end credits rolled on his Port Orchard locale last month. It’s a fate he’s trying to avoid for West Seattle’s faded gem, the Admiral.

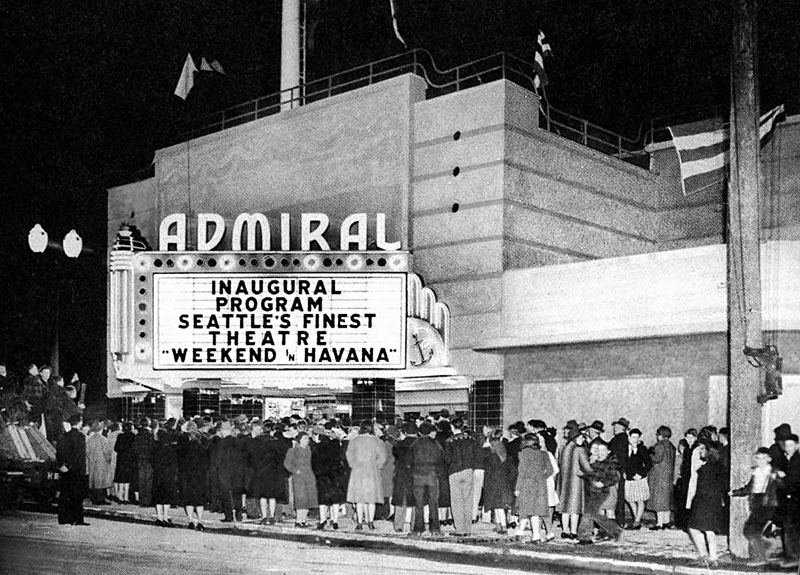

First opened as the Portola in 1919, before the invention of “talkies,” the Admiral is a case study in the changing economics of the theater business. In 1942, when going to the movies was about as glamorous a thing as a family could afford to do, a new owner, flush with cash, expanded the theater to 1,000 seats, renamed it the Admiral, and introduced maritime embellishments like seahorse lamps and a giant mural of Seattle swashbucklers.

Then came the precursor to the Netflix Age: the scourge of Blockbuster. Shut down in 1989, the Admiral reopened three years later thanks in part to the Southwest Seattle Historical Society, which helped secure landmark status for the building. But a new designation didn’t mean new digs.

Today, Brein refers to the Admiral as “tired.” Projectionists still thread the theater’s 35-millimeter film by hand onto platters—spinning plates four feet in diameter—before each show. And the threadbare carpeting and lack of simple modern refinements like cup holders speaks of a screening room stuck in amber.

“The Admiral is a work in progress,” says Brein, with Oscar-worthy understatement.

Still, there are signs of life. Recently, both the Seattle International Film Festival and the Seattle Gay and Lesbian Film Festival made pit stops. Brein says goofy nights like the theater’s monthly Rocky Horror Picture Show showing and a Mamma Mia! sing-along are drawing crowds. And he’s hopeful a landmark grant and loans will provide the cash necessary for the Admiral’s much-needed rehab and reinvention as a first-run theater.

But the Admiral’s own attempts at fund-raising have thus far been unsuccessful. In 2007, a manager skipped town after surreptitiously pocketing the proceeds from selling seat-back personalized nameplates for $40 a pop. And asked to describe the Admiral’s future prospects, one 11-year employee is as blunt as a Tarantino title card: “Closed,” she says.

If the Admiral’s slow demise is like a dreary Ingmar Bergman black-and-white about the indecencies inflicted upon the aged, then Burien’s Tin Theater’s story is its opposite: a sunny, dimpled rom-com with (so far) a happy ending.

The theater’s name is an homage to the building’s origins. Originally the Hi-Line Tin Shop, it sold sheet metal and other hardware in the 1930s. New owner Danny House hung the shop’s original sign over a bar counter—actually an old workbench—and lovingly designated the bathrooms “Ernie” and “Phyllis” in honor of the shop’s original owners.

After buying the building eight years ago, House at first did only what came naturally to him: He sold meat. Known as “Dan the Sausage Man,” House operated a salted-meat gift-basket business of that name out of the building until 2004, when he decided his “Olde Burien” neighborhood was in need of a good restaurant. Then last summer, he converted an old storage shed into a sunken 42-seat theater paneled in cherry wood.

“It wasn’t something I thought would generate money,” says House. “It was just something I thought the neighborhood needed.”

He backed up his pauper’s ambitions with a rarity in the service-industry world: health care for his employees. But packed weekend crowds suggest House might have aimed too low.

“I loved it,” says local David Templeton after seeing Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. “It feels like sitting in a giant living room.”

House is hopeful that the homey warmth customers like Templeton seem to love will carry him and the Tin through an uncertain future. After all, he knows as well as anyone that a moviegoing experience that mimics your own living room can now be had without leaving home.