The biggest armed bank robbery in American history began shortly after closing time on the evening of Feb. 10, 1997, when two men wearing trench coats, sunglasses, and FBI caps approached the door of the Seafirst Bank in Lakewood, south of Tacoma.

Inside, three tellers were preparing to turn out the lights and lock the vault. Lanky 57-year-old Billy Kirkpatrick and his diminutive partner Ray Bowman, 53, had staked out the bank for most of January, taking time to blend in with the locals. As federal documents and testimony would later reveal, the Mutt and Jeff duo lived in a Kent motel, dined at the better restaurants, and attended a piano recital at the University of Washington.

After weeks of casing the bank and devising a getaway route, they were excited to finally stand at the locked door, aware the vault was packed with an extraordinary amount of cash to cover an upcoming payday for soldiers from nearby Fort Lewis. The onetime Midwest shoplifters—they first paired up in the 1970s to boost disco tunes from record stores—had graduated in the 1980s to taking down U.S. banks at gunpoint. Having stolen more than $3.5 million during 26 cross-country heists since then, the duo had earned the FBI honor of a bandit nickname: the Trench Coat Robbers. Agents had no idea who, exactly, they’d been pursuing for almost 15 years, although this would be the two bank artists’ final, and greatest, performance.

Using a small prying tool, the pair flipped the lock on the door and entered with guns drawn. They ordered the women into the vault and secured their wrists with plastic ties, then quickly began stuffing money into duffle bags. Within minutes, using a metal cart to help transport the unwieldy stack of bags, they pushed through the door and loaded their stolen Jeep Cherokee with $4,461,681 in bundled cash. As the Jeep sped off into the winter darkness, it sat low in the back, toting a payload roughly equal to a NFL lineman.

The Trench Coats got away clean, only to be deceived by the money itself. They took so much cash they couldn’t successfully stow it in their homes and cars. Before the year was out, Kirkpatrick would be stopped by a Nebraska state trooper for speeding seven miles an hour over the limit; during a search of his trunk, he was found to be carrying almost $2 million in a set of footlockers, some of it traceable to Lakewood. Bowman, meanwhile, would make the mistake of paying $174,000 in cash to a log-home builder, whose bank deposit caught the eye of an IRS agent. That was the germ of an investigation that eventually led to the discovery of $480,000 in cash stored by Bowman, some of it bound by a Seafirst money band. By 1999, the crooks had traded in their Trench Coats for prison jumpsuits, and were sentenced to more than 15 years.

In stark contrast is the biggest unarmed bank robbery in Washington state history, which took place nine months ago, and for which no one has yet been caught or named. The victims did not know they’d been robbed until three days later. The thieves had no need for guns, disguises, duffle bags, or a getaway vehicle. No need, even, to be in the state, or on the continent, for that matter: It was a cyberheist.

Whoever took down the Bank of America account of a Leavenworth hospital for $1 million last April—likely Russian and Ukrainian hackers—merely used a computer keyboard. Electronic impulses were the extent of the intrusion it took to capture Cascade Medical Center funds and send them flying off over the Internet to 96 private bank accounts elsewhere. There, human mules—co-conspirators, likely most of them unknowingly recruited by the masterminds—cashed out the holdings, kept a bit for themselves, and sent the rest by wire overseas.

That was the plan, at least. The Chelan County treasurer’s office says it has recovered about $415,000 of the heist, beating some of the mules to the stashed accounts. But the roughly $600,000 loss still ranks as Washington’s largest reported cyberheist—so far. Second to that is the October 2012 theft of $400,000 from the city of Burlington’s account at Bank of America. That hacked bundle was electronically transferred to business and personal accounts elsewhere over a two-day period. Little is publicly known about that Skagit County theft, but a spokesperson for the Secret Service in Seattle, which is probing the heist, confirms that $400,000 disappeared into cyberspace, and cautions that “a lot of these kind of investigations wind up being very lengthy.” In other words, Burlington can likely kiss its money goodbye.

Those thefts, of a combined $1 million, pale in comparison to the global cyberheist of $45 million from two Middle East banks, revealed last year. Six New Yorkers were among those later arrested in the scheme, which involved mules (a “criminal flash mob,” as the tabloids put it) working in 20 countries. They withdrew $5 million on a single day a year ago December and $40 million more one day last February.

“In the place of guns and masks, this cybercrime organization used laptops and the Internet,” Eastern New York U.S. Attorney Loretta Lynch said in a memorable statement. “Moving as swiftly as data over the Internet, the organization worked its way from the computer systems of international corporations to the streets of New York City, with the defendants fanning out across Manhattan to steal millions of dollars from hundreds of ATMs in a matter of hours.”

Bank databases had already been hacked by the cyberthieves, who erased card withdrawal limits and created their own access codes. It’s thought to be the world’s biggest bank robbery, with everyone from Interpol to the FBI to Microsoft’s expanded Cybercrimes Center in Redmond on the trail. (Microsoft has claimed success in combating several major cybercrime operations recently—in particular, botnet or “zombie” spam and scam operations involving networks of computers tied together by malware. MS estimates that as many as five million individual and network computers are corrupted and botnet-vulnerable.)

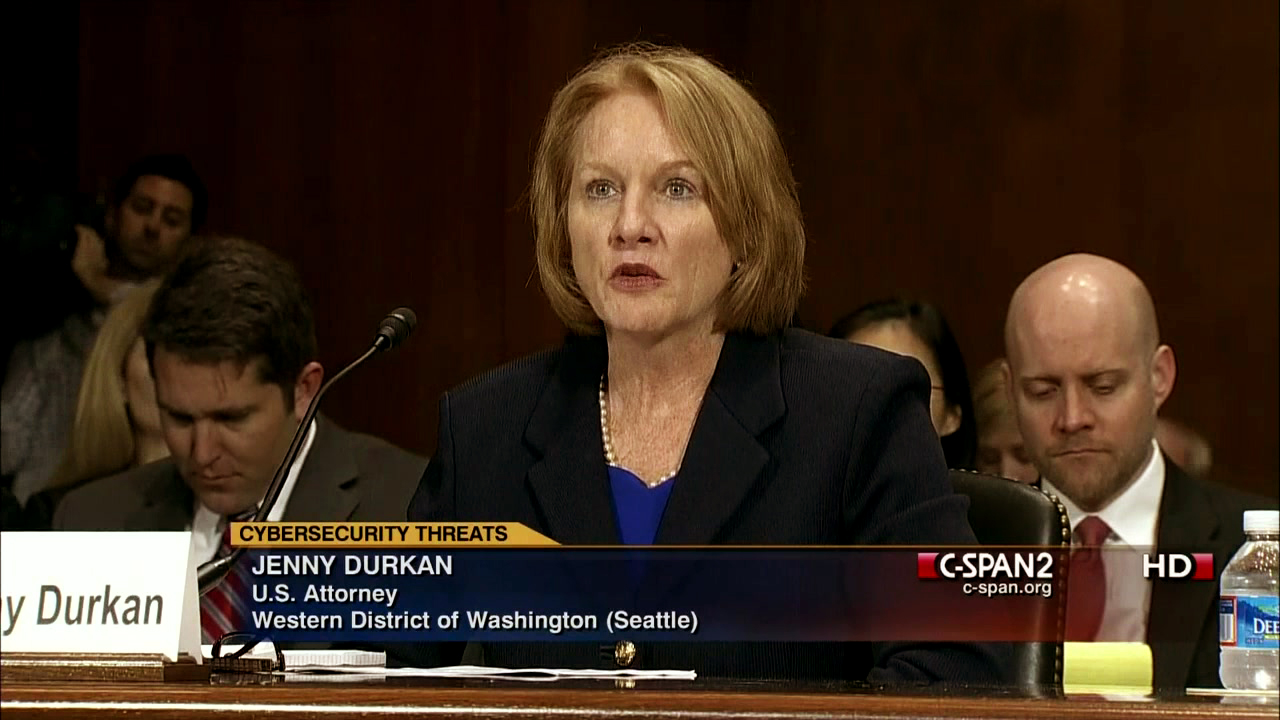

Internet crime is an ever-expanding risk, and “Few things are as sobering as the daily cyber-threat briefing I receive,” says Seattle’s U.S. Attorney Jenny Durkan, one of the nation’s top cybercrime prosecutors, referring to a daily Justice Department bulletin that details successful and attempted cybercrimes around the globe. Last year, Durkan told a U.S. House Judiciary subcommittee how 10 years ago the big concern was solo hackers and spammers. Today the threat comes from organized crime, terrorists, and botnet collectives, among many others. She has also watched her Seattle office expand its prosecutorial horizons, she told Congress, now that “many of our cases involve computers and electronic evidence located in other countries. Many times the offenders are located in another country. But even U.S. criminals will use computers located in another country to hide their tracks. Often it is impossible to identify, arrest, and prosecute offenders without the assistance of foreign governments.”

That’s part of the attraction of the digital underworld—the chance to pull off a caper cheaply and anonymously from afar, at considerably less risk of being discovered before making a quick getaway. Technology has democratized crime. Rather than weapons or burglary tools to gain access, a cyberthief needs only to press the “Enter” key, and he’s in.

For clarity, we’re talking here about cybercrime as opposed to most cyberwar. The latter generally involves commercial and governmental espionage and sabotage waged by electronic intruders, be they bedroom-bound teen hackers or sophisticated political conspirators. In a pop sense at least, cyberwar got its start in Seattle after the locally filmed 1983 movie WarGames became a hit. Though it was fiction, the film, starring Matthew Broderick as a Seattle high-school gamer and hacker who almost launches WWIII, provoked concern among lawmakers, generals, and CEOs. Its impact helped compel Congress to enact the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, expanding electronic protections and imposing harsher criminal sentences. Seattle is now itself a player in war games, thanks to advances by locally based computer giant Cray Inc. It supplies the National Security Agency (the former employer of whistleblower and secrets thief Edward Snowden) and other government and private entities with petaflop-speed supercomputers, ones capable of a thousand trillion operations per second, instantly calculating all sorts of arcane probabilities—or reading your e-mails in a blink.

Typically, cybercrime is the Internet robbery, burglary, or scamming of any computerized site, from major institutions to the average home. It involves cons and fraud, often using malware to infect individual computer systems. Mikael Patrick Sallnert, for example, is a Swedish cybercriminal arrested in Europe last year and brought to Seattle for prosecution. Having pled guilty, Sallnert is now doing 48 months for his role in an international ring that infected computers with scareware. Using this devious software, the ring duped nearly a million victims into believing their computers were infected, then sold them useless antivirus software to fix them, netting an estimated $70 million in the scam. Sallnert operated a credit-card service that processed about $5 million of those payments.

Yet, “Most cybercrime victims are not targeted,” says cybersecurity blogger and ex-Washington Post reporter Brian Krebs, who has been tracking the Russian hackers behind the Chelan heist. “They are victims of opportunity.” Cybercrooks often succeed, he tells me, “by tricking relatively non-technologically savvy people into compromising their systems, or by taking advantage of systems that are not up to date with the latest security fixes. People need to understand that just as walking down the street in a foreign city at night drunk is likely to make you a target for pickpockets and muggers, cruising around the Internet with unpatched systems and browsers is going to get your computer compromised eventually.”

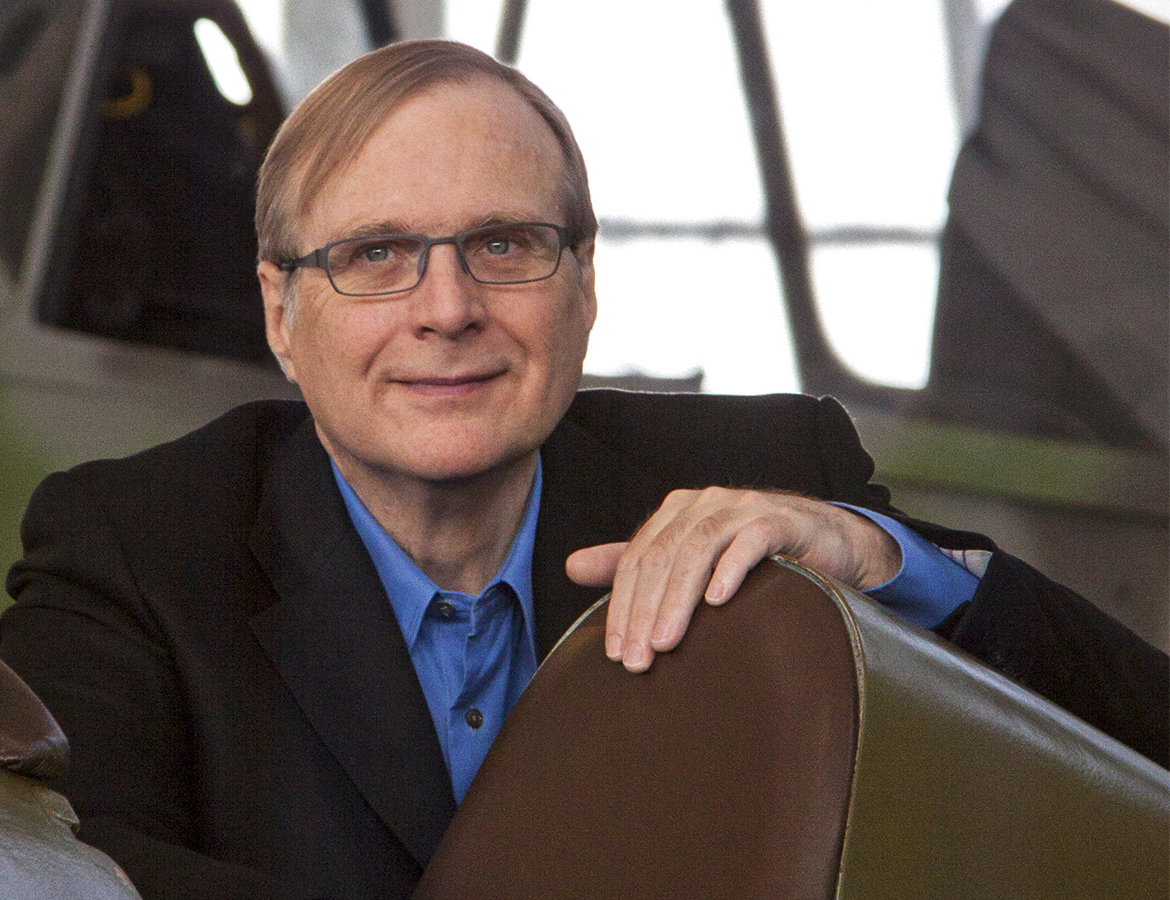

Though we’re all potential victims, it’s the high-profile, and often wealthy, figures we hear about. That was demonstrated in two quirky local cases involving the Mariners’ Felix Hernandez and Seahawks owner Paul Allen. Both were hit by low-tech bandits, prosecutors say, relying on telephones and the Web. That both are rich also made it easier for the scammers, initially at least, to escape notice.

In Allen’s case, Brandon Lee Price, an AWOL Pennsylvania soldier, called up Citibank one day and impersonated the billionaire, convincing a service-center worker to change Allen’s Seattle address and telephone number on his Citibank account to Price’s address and phone, suggesting the Microsoft co-founder had moved to Pittsburgh. Price also got Citibank to send him a new debit card with Allen’s name. He then attempted a $15,000 Western Union cash transaction, which didn’t go through. Turning more practical, he used the card to make an overdue loan payment. Allen, perhaps out cruising on his 400-foot yacht, never noticed.

But the bank caught on, and the FBI crashed Price’s party. His attorney describes Price as undereducated and suffering from the effects of a head injury in his youth. But prosecutors say Price intended to milk America’s richest sports mogul, and even kept notebooks on how to pull it off, including a prepared script he followed when talking to the bank. According to U.S. court records, Price pled guilty to four counts of fraud in October, receiving an eight-month sentence and a requirement to pay $658 in restitution. His mother said in a letter to the court that her 30-year-old son had never been in trouble before and was remorseful to the point of tears after the FBI stormed their home.

King Felix, the Cy Young Award winner whose seven-year, $175 million contract makes him the highest-paid pitcher in professional baseball, told federal investigators that he and his wife Sandra had no idea one of their credit cards was being drained in 2012 by the allegedly cyberscamming wife of another Mariners player. Maria “Jackie” Peguero, married to M’s outfielder Carlos Peguero, is facing three federal counts of wire fraud for making $180,000 in online purchases from Saks Fifth Avenue on Sandra’s card. Like soldier Price, she allegedly phoned in an address change that enabled her to use Sandra’s MasterCard online, placing 60 separate orders over a three-month period and having them shipped to her Fife apartment. (Husband Carlos, still with the M’s organization, also played for the Mariners’ Tacoma farm team last year.) Some single-day purchases topped $10,000.

Seattle Secret Service Agent Ashleigh Audley, who investigated the case as part of the Electronic Crime Task Force, says Saks sales personnel in New York finally caught on when someone realized the items were not being shipped to the Hernandez home in Bellevue. Spanish-speaking Sandra Hernandez told investigators that because of her limited English, friend Jackie had helped her order goods and services as they sat together at Sandra’s home computer. But, as the Hernandezes also told investigators, only their accountant sees the credit/debit-card bills, and was unlikely to notice anything unusual about large purchases. Jackie Peguero, meanwhile, wasn’t exactly hiding her alleged buys: She posted pictures of herself on Twitter feeds and other social media showing off new duds. Agent Audley says that many of the stylish fashion shots, such as Peguero displaying a $200 silk blouse and a $1,750 Gucci handbag, match purchases made with the Hernandez card. Peguero, who has pled not guilty and is being represented by a public defender, may have made other purchases with the card and is likely to face additional allegations of fraud, prosecutors now say. But Peguero, through her attorney, says new information is forthcoming in her defense that “may facilitate a resolution of this matter.”

What happened to the millionaire ballplayer and the billionaire bachelor could have happened on a lesser scale to any average Jane or Joe—though in this economy, they’d perhaps be more alert to spiking bank charges. The elderly and the uninformed are commonly victims of e-mail and social-media cyberscams: the “advance fee lottery” trick, for example, a message saying you’ve won a large sum of money but requiring an advance fee to cover prize-delivery expenses (which can lead to ID theft as well). Fortunately, as security consultant Krebs points out, “Most cybercrime against consumers is reversible: That is, if the consumer is defrauded through their debit or credit card, they may be temporarily inconvenienced, but as long as they file a fraud claim with their bank or credit-card company, they are generally not liable for those charges.” Last week, retail giant Target said as many as 100 million customers may have been affected by a massive pre-Christmas hack attack on its accounts (banks would cover any customer losses but could sue Target to recover those funds). Shortly after the heist, Krebs reported, the stolen card data was already flooding the black market, including to a popular underground store called Rescator, where each card was sold for anywhere from $20 to more than $100 per card.

U.S. Attorney Durkan can speak to card theft not only as a prosecutor but as a victim. Mortifyingly, she admits, she was heisted by a street-level cybercrook, 43-year-old Ana M. Crisan of Renton, whose specialty was rigging walk-up and drive-up ATM machines with electronic “skimming” devices and pinhole cameras. That enabled her to obtain 237 bank account numbers and security codes throughout the West—Durkan’s among them. Before she was caught in 2012 and sentenced to four years in prison (the U.S. Attorney for Eastern Washington handled the case), Crisian managed to steal $125,000. About $1,000 of that was Durkan’s. “I, of all people, knew better,” she said.

Yet who among us checks to see if their ATM is outfitted with a skimmer—a device deftly inserted into the card slot to record account numbers on a magnetic strip—or takes time to check for a tiny camera that records users punching their card security codes onto the keypad? (Thieves also use fake ATM’s—a realistic device that fits over the top of real ATM’s to record numbers and PINs—as well as skimmers that can be attached to cash registers).

The experience did seem to energize Durkan for combat with digital criminals (because of her high profile as a cybercrime prosecutor, she has been targeted by other cyberfoes, including the hacker collective known as Anonymous). Today Durkan chairs or co-chairs several Justice Department cybercrime committees, and has helped draw up such federal measures as the President’s Executive Order on Cybersecurity and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. Her office has brought charges against some prized cyberthieves and hackers, including Daniel Munteanu, a 29-year-old Romanian national awaiting sentencing in Seattle for scamming five eBay customers out of more than $120,000 last year. He was nabbed here attempting to board an international flight.

Munteanu used counterfeit passports to open bank and mailbox accounts to pose as a seller of eBay merchandise—boats, cars, and farm equipment included. (He and co-conspirators pretended to be the sellers, and conned buyers into sending payments into his bank accounts—money he then quickly moved offshore). Another big-time cyberscammer, David B. Schrooten, a 22-year-old Dutch hacker known as Fortezza, received a stiff 12-year sentence in Seattle last year for trafficking in stolen credit-card numbers worldwide. In October, Charles T. Williamson, a 36-year-old California rap artist who performed under the name “Guerilla Black,” received a nine-year sentence as part of Schrooten’s crime ring.

Durkan is a proponent of stiffer sentences for some Internet crimes. Last March she urged Congress to simplify some sentences and “enhance penalties in certain areas where the statutory maximums no longer reflect the severity of these crimes.” (She cited the five-year maximum imposed in cases where hackers break into databases and steal credit-card numbers, arguing they deserve more time.) She also urged lawmakers to make the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act subject to the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), making conspiracy prosecutions easier.

But federal prosecutors are already handing out harsh penalties when they see fit—or want to send a message. Critics cite the case of 32-year-old Barrett Brown, supposed spokesperson for that Durkan-targeting hacktivist collective Anonymous, who has spent more than a year in a Texas jail and faces up to 105 years in federal prison if he’s convicted of a litany of hacking and conspiracy charges. Another Internet activist, Aaron Swartz, 26, faced up to 35 years and a $1 million fine for wire and computer fraud after allegedly illegally downloading academic journals. When prosecutors twice rebuffed his bids for a plea bargain, the onetime Harvard fellow ended up hanging himself in his Brooklyn apartment last January. A memorial for Swartz in the other Washington drew such opposites as Republican Rep. Darrell Issa and Democrat Sen. Elizabeth Warren. “Stick it to the man,” Issa, an open-Internet advocate and author of a Digital Citizens’ Bill of Rights, told the crowd, according to a Huffington Post report. “[Aaron] and I probably would have found ourselves at odds with lots of decisions, but never with the question of whether information was in fact a human right.”

Eight-year and six-year terms were handed out to Seattle cyberthieves John Earl Griffin, 36, and Brad Eugene Lowe, 39, respectively, in 2012, although their crimes were a mix of on- and offline capers. They used a technique known as “wardriving,” cruising Seattle in a vehicle outfitted with a receiver to detect wireless networks. Once connected, they could electronically enter business networks and computers. They also literally broke into businesses, through doors or windows, and installed malware on computers, enabling them later to obtain codes and passwords over the Web. They accessed payroll and business accounts and bought items from Amazon and eBay. Until busted by Seattle police, the twosome hacked or burglarized 50 businesses for more than $3 million in losses over a three-year period. “They were sophisticated in technology . . . and livin’ large,” Durkan said.

Her office was also hoping to prosecute a high-profile hacker named Dmitry Olegovich Zubakha, a Russian who was detained in Cyprus last summer, suspected of botnet attacks on Amazon’s network and other e-commerce sites, disrupting customer access. Zubakha’s arrest made global headlines, and seemed to reflect the cooperative nature of international agencies in combating cybercrime. “That was a great case,” a federal official familiar with the case tells me, “with Interpol and the Cypriot government aiding in the arrest.” But a less-noticed development has left U.S. officials dismayed. Though Zubakha was thought to be ticketed for Seattle, “The Russian government had a different take on the case,” says the federal source, “and actually wound up counter-extraditing him to Russia.” Aleksey Gordon, who blogs about the Russian Mafia, writes that Zubakha was actually employed “on staff” by the Kremlin, and though he’s in Russian custody now, “there is no doubt that this will not last long” and he’ll be freed.

Perhaps because of the Zubakha arrest at the FBI’s request, Russia recently began warning its hackers not to travel abroad. As Wired reports, Russia has been mostly a safe haven for professional spammers, hackers, phishers, and fraudsters who attack the U.S. In September, the government issued a warning advising Russian “citizens to refrain from traveling abroad, especially to countries that have signed agreements with the U.S. on mutual extradition, if there is reasonable suspicion that U.S. law-enforcement agencies” have a case pending against them. “Practice shows that the trials of those who were actually kidnapped and taken to the United States are biased, based on shaky evidence” and are slanted against the Russians, the notice states.

A fair number of Russian cybercriminals have been arrested by U.S. authorities in recent months, including alleged hacker Aleksander Panin, being held in Atlanta where he’s charged with a $5 million online bank fraud. When he was nabbed in the Dominican Republic last summer, Russia called his extradition “vicious” and “unacceptable.”

That’s sort of how they felt over in Chelan County in April—once the treasurer’s office opened that Monday morning and officials learned the public’s money had been extradited. To Russia, no less.

On Wednesday, April 24, five days after the Leavenworth heist and two days after it was discovered, security blogger Krebs began calling Cascade Medical Center officials to tell them who likely robbed, or burglarized, their bank account. The Russian cyberheist was carried out with the help of nearly 100 different accomplices in the United States, who were hired through work-at-home job scams run by a crime gang that has been fleecing businesses for the past five years, Krebs wanted to tell hospital officials. But nobody ever called back, he says. As he later recounted in his blog at krebsonsecurity.com, he reached out shortly after hearing of the heist because he’d spoken with two unwitting accomplices who’d helped launder more than $14,000 taken from the hospital’s accounts.

One of them, 31-year-old Jesus Contreras from San Bernardino, Calif., had been out of work for more than two months when he received an e-mail from Best Inc., a company supposedly located in Australia. A representative of the “software development firm” said he’d found Contreras’ resume on careerbuilders.com and that he seemed qualified for a work-at-home job forwarding payments to overseas software developers, keeping eight percent of any transfers. All he needed was a home computer. Contreras, desperate to find work, signed on.

On April 22, Krebs recounts, “Contreras received his first (and last) task from his employer: Take the $9,180 just deposited into his account and send nearly equal parts via Western Union and Moneygram to four individuals, two who were located in Russia and the other pair in Ukraine. After the wire fees—which were to come out of his commission—Contreras said he had about $100 left over. ‘I’m asking myself how I fell for this because the money seemed too good to be true,’ Contreras said. ‘But we’ve got bills piling up, and my dad has hospital bills. I didn’t have much money in my account, so I figured what did I have to lose? I had no idea I would be a part of something like this.’ ” It didn’t pay off, either, at least for Contreras. Bank of America, tracking the transfers after Chelan County discovered the losses, froze Contreras’ account and those of others involved.

The county treasurer’s office did not respond to our requests for comments, and the Spokane office of the FBI is still investigating the case. But county treasurer David Griffiths told The Wenatchee World last summer that $414,800 had been recouped by the bank, with another $100,000 in disputed funds that could later be recovered. The rest, roughly $500,000 to $600,000? “It’s gone,” Griffiths said. “Probably gone to Russia.”

The fake company that hired Conteras and others, Krebs notes, is part of a transnational organized cybercriminal gang operating in Russia and Ukraine. “Its distinguishing feature is that it operates its own money mule recruitment division. This eliminates the middleman and increases the gang’s overall haul from any cyberheist.” The gang has several telltale signatures and has hit small to mid-sized organizations, stealing many times more than the millions taken from Chelan County, Krebs thinks. In fact, he suspects the county may have got off easy.

“The bank accounts that were hacked also are used to administer 54 other junior taxing districts in the county,” he says. “My guess is this attack would have been worse, but that the fraudsters simply exhausted their supply of money mules.

“Just as real-life bank robbers are restricted in what they can steal by the amount of loot that they can physically haul away from the scene of the crime,” he adds, “the crooks behind these cyberheists are limited in how much they can steal to how many money mules they can recruit to help launder the fraudulent transfers.” As Billy and Ray, the Trench Coat Robbers, might say, it still comes down to the size of your Jeep.