IF YOU WERE an N.Y.C. resident and tabloid reader, as I was, in the late ’80s, Capturing the Friedmans (which opens Friday, June 20 at Harvard Exit) sounds superficially familiar: A schoolteacher and one of his three sons are accused of horrificsome might say implausiblechild-sex- abuse crimes. Hysteria ensues; TV trucks swarm the cul-de-sac; convictions are inevitable. Case closed. But step back a decade, as director Andrew Jarecki has done in this methodical, even-handed documentary (his first), and things begin to look very different.

Yes, something bad probably happened, but nowhere near the scale represented in Newsday and The New York Post. Instead, perhaps incredibly to some, the Friedmans themselves begin to look like victimsalthough this documentary never descends to Oprah-level triteness about a family torn asunder. The crimes, if any were committed, remain a mystery, and Capturing preserves that mystery, drawing no ultimate conclusions beyond the Friedmans’ humanity.

Despite the screaming headlines, the Friedmans seem completely ordinary and familiar, almost like characters in a sitcomwarm, quarrelsome, Jewish, Long Island to their core. Patriarch Arnold is a frustrated musician who once performed as “Arnito Rey” on the borscht belt. But even after he gave up showbiz for family and career, he kept the cameras rolling at home. And rolling. And rolling. Jarecki unearthed a literal archive of home movies, photos, and audiotapes. To the Friedmans, it seems, life was not worth living unless documented in all media, in good times and bad.

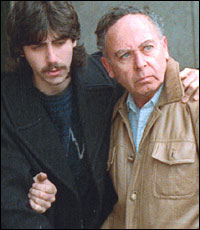

Cavorting before the lens, Arnold and his three sons are like exuberant, innocent vaudevillians in their home movies (which come complete with credits and title cards). Looking on from the side of the frame, reluctantly photographed or interviewed, is mother Elaine, the reticent stage manager pointedly excluded by this merry troupe.

Jarecki alternates between recent interview segments and old footage as he relates the case. A 1985 child-porn- magazine sting operation by the postal service leads to a 1987 search warrant, which leads to allegations, arrest, trial, and convictions by 1988. Cops, lawyers, and judges remain secure in the verdict despite a lack of evidence and testimony that, as the U.W.’s Elizabeth Loftus has shown with so-called “recovered memories,” seems thoroughly coached and manufactured. There is no narrator to provide false objectivity or tell us what to think. The Friedmans speak for themselvesby turns funny, angry, and self-pitying. Believe what you like about them, the film says.

IN WATCHING THIS, one asks disbelievingly: How could they not have known about Arnold’s subsequently admitted pedophilia? Then the harder realization begins to seep in through Jarecki’s compellingly faceted, Rashomon-like account: How can you really know the truth about anyone in your family? How well do you know your father? Your mother? Yourself? Then things get even more murky and unknowable when it comes to sex. Elaine had her doubts about her husband; of their foreplay, she says, “He treated it like work.” Yet their sons bought into the image Arnold so assiduously cultivated in his home movies: that of the happy, normal family. Someone observes, “Arnold liked pictures”which were both his succor and his undoing.

In this way, Capturing is as much about media as family: the lure of the forbidden image (kiddie porn); the misleading superficiality of home movies and snapshots; the destructive power of the TV-newspaper media cyclone. Yet the film isn’t cold or “meta” in its systematic deconstruction of the Friedmans themselves and their media representations. No matter how elusive the truth and how contradictory the accounts, you end up caring tremendously about this familyas Jarecki obviously does, too.

We’ve had our own Northwest child-sex-ritual-satanic-abuse witch hunts in the Northwest (Olympia’s late-’80s Ingram case; Wenatchee in the mid-’90s), and I never thought I’d see a better examination of the phenomenon than Frontline‘s early-’90s series on North Carolina’s Little Rascals day-care case. But Capturing is better, almost sure to make my top-10 list this year and probably that of every other critic in America. Inevitably, such witch hunts collapse like a house of cardstragically too late, however, for those who live inside.