Following years of negotiation, Seattle has made public a tentative agreement with the Seattle Police Officers Guild, the city’s largest police union.

On Monday, the Seattle City Council introduced legislation to authorize the long-awaited contract, referring it to the full council for a vote that could occur as early as next week. If approved, the 100-page tentative agreement would become retroactively effective on Jan. 1, 2015 — the day after the previous contract expired in 2014 — and expire on Dec. 31, 2020. Seattle’s rank-and-file police union voted 96 percent in approval of the contract that guarantees pay raises, according to Mayor Jenny Durkan’s office.

“Even as homes, groceries, and gas have become more expensive in our city, our officers continued to keep our residents, neighborhoods, and businesses safe. At the same time, they have served as a model nationwide by bringing SPD into full and effective compliance with the federal consent decree,” Durkan said in a statement. “This contract is critical to meeting the public safety needs of every neighborhood and community in our city and continues the important job of reform while helping ensure Seattle can hire and retain the best police officers.”

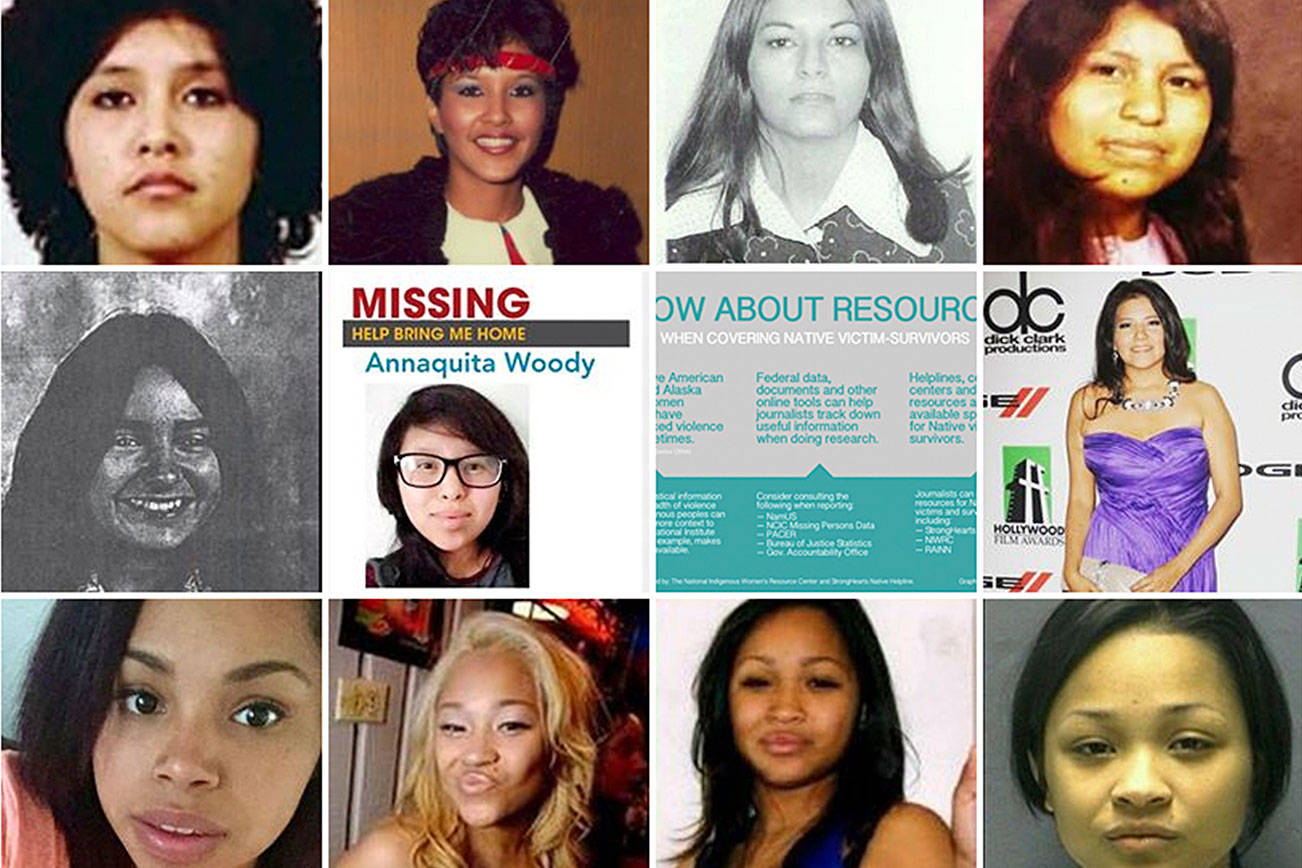

The tentative agreement is a linchpin of the police accountability legislation passed in May 2017, which was designed to ensure checks and balances of the Seattle Police Department (SPD) by creating three oversight agencies. The legislation made permanent the Community Police Commission (CPC), which was established under the 2012 consent decree. It also created a civilian-led agency called the Office of Police Accountability (OPA) that investigates police misconduct complaints, and an independent auditor of the police called the Office of Inspector General.

If the collective bargaining agreement is approved by the city council, guild members would receive pay raises amounting to 3 percent for 2015 to 2017, 3.65 percent for 2018, 3.85 percent for 2019, and a percentage increase determined by the Consumer Price Index plus 1 percent for 2020. In addition, employees who are required to wear body cameras would receive a 2 percent pay increase.

In exchange for the raises, the police union has agreed to reforms including outfitting all front line officers with body worn cameras, the addition of civilians in OPA and Human Resources leadership positions, and the withdrawal of Unfair Labor Practice claims.

“The Seattle Police Officers Guild would like to thank Mayor Jenny Durkan, who inherited this ‘contract mess’ from her two predecessors, who unfortunately, did not choose to respect the labor laws of Washington,” SPOG President Kevin Stuckey said in a statement. “From the onset, Mayor Durkan made getting a new SPOG contract a top priority and her team followed her leadership and got the work done at the bargaining table.”

Monday’s legislation comes nearly a year after U.S. District Judge James Robart, who is charged with overseeing reforms aimed at reducing biased policing and the use of excessive force, ruled that SPD had fully complied with the first phase of federal oversight. The January ruling ushered in a two-year period in which the police must demonstrate sustained improvement before the consent decree can be lifted once and for all. Robart’s 16-page ruling also required that the city reach a new collective bargaining agreement with SPOG that didn’t compromise the police accountability legislation passed last May. “If collective bargaining results in changes to the accountability ordinance that the court deems to be inconsistent with the consent decree, then the city’s progress in Phase II will be imperiled,” Robart wrote.

Some CPC commissioners have already expressed dissatisfaction with the agreement. In a statement after the public release of the tentative contract, the group indicated concern that the agreement may not meet the requirements of the 2017 police accountability legislation.

“From a review of the contract by some members of the CPC, it appears that the tentative contract gives up many of the reforms won in the landmark Police Accountability Legislation. That legislation was passed by the city council after a long struggle, with an 8-0 vote last year after receiving broad community support,” the Community Police Commission wrote in a statement. “The CPC was not consulted at any stage of the negotiation process regarding any of the substantive concessions we see in the tentative agreement. We have a public meeting of the full Community Police Commission scheduled for Wednesday, Oct. 17, to discuss our analysis of the contract and our next steps forward.”

Some discrepancies between the police accountability legislation and the tentative agreement that may pose a problem for the federal court includes language in the ordinance that requires employees to be held to the same standards of accountability regardless of rank; however, the collective bargaining agreement does not explicitly state that accountability policies will be equally applied to all guild members. Moreover, an appendix in the tentative agreement states that the collective bargaining agreement (CBA) will supersede the ordinance, should any disagreements in the languages arise: “In the event there is a conflict between the language of the ordinance and the language of the CBA or the explanations and modifications in this appendix, the language of the CBA or this appendix shall prevail.”

Another possible issue is the time limit on misconduct investigations. Although the tentative agreement provides an extension on the 180-day deadline for misconduct allegations to be investigated when warranted, it depends on the amount of time that is left on the clock. For instance, no extension will be allowed at the 120-day mark, but a 30-day extension will be permitted at the 150-day mark, and 60 days will be permitted at the completion of the 180 days. The ordinance, on the other hand, explicitly states that 60 additional days will be provided when new information is brought forward.

The CPC plans to discuss its analysis of the contract during a public meeting scheduled from 9 a.m. to noon Oct. 17 at the Seattle Municipal Tower.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com