Djin Kwie Liem thought only of his fish.

Forced to flee when the power vanished, black smoke swirling from the roof of the Wah Mee building, the tiny old man, still blessed with a child’s smile, recalls saying to himself, “Oh my God, I just got them, shipped from Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan: 5,000 fish, maybe more! Ten thousand dollars!

“Allahku!”

A wise yearly investment, Liem knew, for Chinese families would venture to his crowded little pet shop during the Christmas holiday and carry home in plastic bags the Japanese coy and the comet-tailed goldfish, in time for the arrival of Chinese New Year the following month.

“They are a sign of prosperity, of plenty,” Liem says, sipping black tea at Duk Li Dim Sum on a cold, rain-soaked morning last month. “It is our custom to keep fish in our homes to send away the bad luck. Some will buy the less expensive fish and release them into the lake. It is a do-good gift, an offering to God.”

It was late afternoon, Christmas Eve. Under leaden skies and a weepy rain, the flames flickered atop the long-abandoned top floor of the building at 665 South King Street—the geographic heart of Chinatown. The cause of the fire may never be known, though arson is suspected. Maybe, as some speculate, the building is haunted—the ghosts of Washington’s deadliest-ever massacre still stir in the basement, home to the inglorious Wah Mee Club.

Liem was in his store, at ground level, chatting with customers—many of them older patrons, the ones who remember the frantic squawk of exotic birds after Liem, newly arrived from his homeland of Malaysia, opened the store in 1979. In those early days he sold small boa constrictors and pythons from Thailand, scorpions and African turtles and monkeys—and silky green iguanas that the braver children would let crawl up their skinny arms when brought here on school field trips.

“Sometimes the snakes would get out. The kids would forget to put the lid back and they’d end up on the streets. People very frightened,” recalls the 77-year-old Liem, smiling at the memory. “I did this not to make money. It was my hobby.”

Liem stood alone on the street that dark night as sirens screamed and tired cooks from nearby restaurants, heavy with greasy odors, smoked cigarettes and looked on as water from fire hoses flooded his store, damaging it beyond repair. The electricity gone, Liem’s fish, once skittering bright in a hundred tanks, went belly-up, their heat and oxygen supply lost.

“My heart broke,” Liem says, wiping a cloud of film from his heavy glasses.

Liem lives by himself in Lake City. Since the fire, he comes each day to Chinatown, wandering through one of Seattle’s most fragrant and colorfully diverse neighborhoods, with a population of nearly 4,000.

Sometimes Liem will gaze out upon a smattering of seniors practicing tai chi in Hing Hay Park, or breathe in the smells of grilled meat from the Green Leaf, or perhaps fetch a bowl of wonton soup, capped with sprigs of cilantro, at the Fortune Garden. Liem’s Pet Shop, you see, was a fixture on Maynard Alley. It was his life, his social center.

“He’s a lost soul now,” says Anita Woo, whose family owns the 105-year-old building and who rented the space to Liem for just $450 a month. “He wants to come back and open again, but that won’t happen now. Too much damage, and so much loss.”

For Liem, not even 5,000 fish could fend off bad luck.

The Woo family, after repeated consultations with architects and city structural engineers, determined in March that nearly half of the building destroyed in the blaze must be torn down—that is, the entire west wall of the structure facing Maynard Alley: Liem’s home away from home for 35 years.

Early next month, the demolition of the wall and clearing away the debris will begin.

The mystery fire robbed many others as well of their livelihood, at least until demolition and reconstruction are complete. Part-owner Tanya Woo says it will take two months to shore up the west side of the structure, and up to two years for the building to be fully restored. Whatever the case, stresses her brother Timothy Woo, the place his uncle Paul Woo bought more than a half-century ago will remain an integral part of Chinatown.

“We will preserve as much as we can,” Timothy says. “The building is too important not to. It has done good things for this neighborhood, for our community. You know, we never made any money out of the building. It’s been like a family heirloom.”

The Sea Garden restaurant, on the east side of the Wah Mee—famous for its whole crab in ginger sauce—remains shuttered and deemed too dangerous to enter until repairs are made. Same with Palace Decor & Gifts, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, and the Yuan Sheng Hang medicinal herb store, whose owner burst into tears and broke a teacup while carrying away as much as she could after being told by the fire department she had 30 minutes to gather her belongings.

Closed too, at least for now, is the famous Mon Hei Bakery.

“When it opened in 1978, the Mon Hei—it means ‘a thousand years of happiness’—it was Chinatown’s first bakery,” says Aaron Chan, whose family has run the place from the beginning.” This is where people came for pineapple buns and egg tarts, moon cakes, rice cakes, pound cakes, and sponge rolls, all glistening in rows behind a storefront window.

“It was like Krispy Kreme when it opened. There were lines around the block,” marvels Chan. “My grandfather, Hung Fok, ran a pastry school in Hong Kong. One day, Paul Woo came into his school. He was on his honeymoon, and he’d heard about my grandfather. So he tracked him down and implored him to come to Seattle and open a bakery in his building.”

The closing of Mon Hei has been tough on his parents. “This is their lifeblood. It is all they have ever done. They have no other skills.”

After a lengthy pause, the 30-year-old Chan ruminates, “It was disheartening, I have to say, when after the fire all that the media mentioned was that this was the place of the Wah Mee massacre, and nothing else. There was little or nothing about all the good things that this building has meant for the community.”

It began as a boarding house, built in 1909 by three Scandinavian men, who named it the Nelson, Tagholm & Jensen Tenement. Later it became the Hudson Hotel, and soon after the Louisa Hotel: 120 rooms for Chinese, Japanese, and thousands of Filipino immigrants—“Alaskeros,” they were called—who would stay in Seattle before being dispatched by labor contractors to work in Alaska’s sardine and salmon canneries.

The thrilling prospect of unearthing gold brought a wave of Chinese into the neighborhood in the late 1800s. They called America “Gold Mountain,” but they endured simmering resentment and discrimination by white laborers in Seattle when a nationwide depression took hold in 1873.

As local historian L. Kingston Pierce wrote, “ ‘The Chinese must go’ became a rallying cry—one that intensified after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, forbidding further immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States and denying citizenship rights to those already settled here.”

The Louisa was something of a sanctuary, and in the 1920s and 1930s, Chinatown throbbed with excitement. Paper lanterns and glowing neon hung from the stoops of apartment dwellings. Children pitched baseball cards in Canton Alley. Adults gathered in social clubs, tucked away in basements and backroom parlors, for card games, and feasted on platters of chaswei, sweet barbecued pork, boiled peanuts, black sesame-seed soup, and good-luck oranges for a sweet, long life.

The hotel, with its orange brick facade and windows with cast-stone sills and lintels, boasted a second-floor billiard room where seven two-story bay windows allowed light to stream in. Rumors persist that a secret casino with a surreptitious passageway may also have been on the second floor. Gorgeous floor-to-ceiling hand-painted murals, destroyed in the Christmas Eve fire, depicted comforting scenes from the Chinese homeland.

The Chinese Community Billboard, now a Seattle historic landmark, was plastered to a wall outside, where it remains today, next to the Sea Garden. It provided, and still does, a public forum for news and messages, especially for seniors who read no English. Since the fire, it languishes behind the cyclone fence that circles the forlorn Wah Mee, the board devoid of anything new save a notice of a January public hearing about the future of Hing Hay Park.

The rooms at the Louisa were small, made of wood and plaster, a communal shower down the narrow hallway on each floor. Men slept on hard cots. Of course there were mah-jongg tables, and at night one might hear, on bustling King Street below, the clack-clack of ivory tiles washing against one another.

“People don’t think of the history and the beauty that was in this building,” muses Anita Woo. “This was a special place. It meant so much to the early immigrants. It is a huge part of the history of Chinatown.”

Says Rebecca Frestedt, the city’s historic-preservation coordinator for the Chinatown International District: “This building is not yet a landmark, but it is so much a part of the fabric of the larger historic district.”

As Roosevelt’s New Deal put a few dollars in people’s pockets, Jackson Street, which runs through the neighborhood, emerged as the hotbed of Seattle’s jazz scene. The Northwest Enterprise, a Seattle-based African-American newspaper, penned this about Jackson Street in the early 1930s: “[I]t attracts persons from all sections of the city and numerous migrants who are attracted by the bright lights and allurements. And there are allurements, if you know where to find them . . . Jackson Street might be called the ‘Poor Man’s Playground.’ Here all races meet on common ground and rub elbows as equals. Fillipinos [sic], Japanese, Negroes and whites mingle in the same hotels and restaurants and there is an air of comradeship.”

Or as Steve Griggs, a local music writer and member of the Jazz Journalists Association, put it recently, “Asian businesses welcomed the African-Americans, and African-Americans appreciated having access to their restaurants.”

University of Washington history professor Quintard Taylor, for an article in the Great Depression Washington State Project at UW, said that the Jackson Street clubs “were the only places where well-to-do white businessmen and socialites met black and Asian laborers and maids as social equals.”

Noodles Smith, owner of the Black and Tan, where Duke Ellington played, sensed a thirst for a sophisticated Great Gatsby–like club, and opened the Ubangi inside the Louisa Hotel in the mid-’30s. It was a glamorous joint, awash in potted palms and exquisite African-themed decor. Music and dance acts flew in from Los Angeles. Cab Calloway played the Ubangi. Nearby was the Congo Club, the 411 Club, the Blue Rose, the Entertainer’s Club—where pianist Jelly Roll Morton performed—and the Bucket of Blood, a rowdy joint which earned its name after someone was murdered following a police raid.

As historian and writer Paul De Barros, in his book on Seattle’s speakeasies, Jackson Street After Hours, wrote, “Imagine a time when Seattle . . . was full of people walking up and down the sidewalks after midnight. When you buy a newspaper at the corner of 14th and Yesler from a man named Neversleep—at three in the morning. When limousines pulled up to the 908 Club all night, disgorging celebrities and wealthy women wearing diamonds and furs. When ‘Cabdaddy’ stood in front of the Rocking Chair, ready to hail you a cab—that is, if he knew who you were.”

Of all the gambling joints in Chinatown, none rivaled the Wah Mee Club in terms of sheer elegance. It was one sexy place in its time—and what a run it had. From its earliest years in the 1920s, when it was called the Blue Heaven, through the 1950s, the Wah Mee, secreted away in a spacious basement space in the Louisa Hotel, reeked of delightful decadence.

There was dancing, and boozing at its long, sumptuously curved bar; mah-jongg and pai gow, and stacks of silver dollars on gambling tables beneath dimly lit ornamental lanterns and rich deep carpets. Smoking Lucky Strikes, people of all races partied hard into the night, their waiters clad in white suits and black ties.

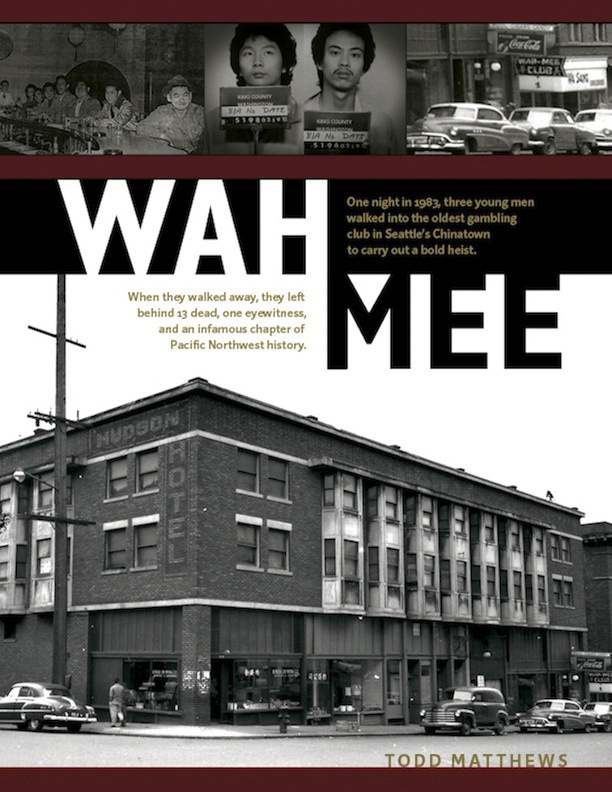

“The Wah Mee was host to some of the highest-stakes gambling in Seattle,” notes Todd Matthews, a local journalist who spent a decade researching and writing an e-book about the Wah Mee massacre, which he published in 2011. “Winners,” he wrote, “went home with tens of thousands of dollars after a single night of gambling. Indeed, gambling was so popular at one point that, according to Jerry F. Schimmel, an authority on coin collecting and author of Chinese-American Tokens From the Pacific Coast, the Wah Mee Club issued its own brass token for gamblers—a 39-millimeter-wide gem with the club’s name written in Chinese characters.”

The place operated illegally, like at least 40 other illicit clubs in the Chinatown area, police estimate. Security was strict and required those entering to pass through a series of doors where private members were “buzzed” in through each door. The conspicuous gambling den was often raided, and in the early 1970s, the Wah Mee, whose English translation is “beautiful China,” fell on hard times—as did the rest of the former hotel.

The March 20, 1970 Ozark Hotel fire at 2038 Westlake Ave. claimed the lives of 21 people. A year later, 12 people were killed at the Seventh Avenue Apartments. Both tragedies led to major city code changes, mandating that every building three stories or less have fire-resistant stairways and door, or a sprinkler alternative.

The new ordinance proved too costly for many Chinatown hotel owners—including building owners Minnie Nelson Harrison and her brother William “Billie” Nelson. They sold the building to Paul Woo, who’d make his nut renting to ground-floor retailers (though for generously low sums) and leaving the top two hotel floors vacant, as they’d been for years—too expensive to repair and abide by the new fire code.

To this day, at least six Chinatown hotels and apartment buildings sit idle, notes Maiko Winkler-Chin, director of the Seattle Chinatown International Preservation and Development Authority—the Eclipse Hotel, the Hip Sin Association Building, the Kong Yick Apartment, and the Gee How Oak Tin Hotel among them, save for some street-level retail outlets. “It has been a problem for a long time here. It’s a cultural thing; the owners don’t want to take on debt, because they’re not sure whether they’ll recoup their investment,” observes Winkler-Chin.

By the 1980s, the Wah Mee Club had lost all vestiges of its former glory. It was just another cocktail lounge, as Todd Matthews details in his book Wah Mee—a dive bar, really, with old couches, cheap plastic ashtrays, and a map of mainland China tacked to the wall, near a framed portrait of a race horse and a Chinese lunar calendar.

On the night of February 18, 1983, one of the most infamous chapters in Northwest history began to unfold when Kwan Fai “Willie” Mak, a club regular, arrived at the notorious nightclub just before midnight. He’d lost a lot of money gambling and he wanted it back. He brought two friends, Wai-Chiu “Tony” Ng and Benjamin Ng. They managed to get past the guards carrying semi-automatic weapons.

Patrons were ordered to the floor, hogtied, and robbed. Thirteen people were executed. Mak and Benjamin Ng were ultimately sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. Tony Ng was charged in the murders, but claimed Mak forced him to participate in the mayhem. The jury found in Ng’s favor and convicted him of robbery. Ng was released by a state parole board last October, after 30 years in prison.

“The Wah Mee,” says Winkler-Chin, “cast a pall over the district for a good while. It was a scary place to go.”

The club’s doors have been padlocked, and no one has entered the gambling parlor since the massacre. It is a tomb now, a time capsule.

Says Tanya Woo, “In respect to the families, we sealed the door after that night. Everything there is untouched, the patrons’ cups, jackets, the doorman’s lunch.”

There are many stories in Chinatown, and many secrets. No other place in Seattle feels so palpably foreign. So much has changed, and yet so much remains the same: the smells and vibrant colors; the buildings with parapet walls, many of them ornamented with signs in Chinese and Japanese; the historic gate across from Union Station, with upturned eaves and bathed in lucky red to welcome people to old Chinatown.

“There is much tradition here, and we’ve held on to our traditions,” reflects Anita Woo. “The young take care of the old. Yes, we have changed as a community, but we stay together. We always stay together.”

Harry Chan owns the Tai Tung, the district’s oldest Chinese restaurant. On any given day, you’ll catch him at the counter, where behind him menu items written in black magic marker on separate pieces of paper are taped to the walls.

He’s lived all of his 66 years in Chinatown, and sometimes pines for the past. `“A lot of the old people have moved out,” he begins. “There used to be so many social clubs for gambling. Now they go to the casinos. The casino buses stop here and take them away. They get coupons for free buffets. That hurts business.

“Oh, yes, it used to be so busy. People out at night, drinking and eating. The old people miss that. Everyone knew each other,” Chan continues.

After bringing a huge, steaming plate of chicken chow mein to a couple of construction workers, Chan adds, “But there are good changes here now. You know, we have the pinball museum, a pizza place [World Pizza], and many new young people are coming, too. This is a good thing.”

Up the street, on South Weller, the sweet smell of fortune cookies permeates the cold air on a brilliant blue February morning. Tim Louie sits in his tiny office at the Tsue Chong Company, which his grandfather opened in 1917. With 40 employees, it’s one of the largest noodle and fortune cookie makers.

“I’m still using Grandma’s cooking recipe for the cookies,” says Louie, 52, whose company turns out 80,000 cookies a day. He’s a popular man in the district, a funny, garrulous sort whom many in the neighborhood call “the unofficial mayor of Chinatown.” Asked who writes the fortunes, Louie replies with a wink, “A very wise Chinese guru.”

Louie turns serious now. He’s got something on his mind. “We got some changes going on here. Not good ones. Parking is bad. My suppliers hate it. They get tickets all the time. They tell me, ‘Tim, I can’t afford to come here.’ There’s a lot more street people here now, too. More crime, it seems. [City Councilman] Tom Rasmussen was down here a while ago. People were coming up to him, asking for money.”

Still, Louie is hopeful. He and many others in the community realize the neighborhood will retain its place as a regional hub for Asian/Pacific Islander culture and commerce. The street cars, light rail, new apartment buildings, and the conversion of old historic buildings into bustling mixed-use developments will lure a new generation of Asian immigrants into the heart of the city.

For now, though, Louie is thinking about his fortune—fortune cookies, in particular. Grabbing a carton of hundreds of thin paper fortunes, he confides, “My dad comes down here every day. He’s 89, but he wants to keep busy. My mom does too. She comes down and stacks the fortunes and puts them in little boxes.”

“How come they don’t call Ballard the International District?” asks Brien Chow—son of the legendary Ruby Chow, a three-term King County councilwoman who in 1948 opened Seattle’s first Chinese restaurant outside of Chinatown. (As a high-school kid, Bruce Lee worked for a time at Ruby Chow’s, in the Central District at Broadway and Jefferson.)

Chow’s mocking comment is representative of the feelings of many in the local Chinese community who to this day bristle at the hybrid moniker adopted by the city of Seattle in 1998: Chinatown–International District. Some still maintain that that designation was intended to disguise or diminish their historical leadership in the area.

The controversial name evolved slowly. In essence, the ID, its often-used shorthand moniker, is essentially three boroughs pressed together. Chinatown comprises the blocks around King Street; Little Saigon centers on 12th and Jackson; and Japantown, or Nihonmachi, is in the vicinity of Main Street, anchored by the Panama Hotel—where in a dimly lit basement remain worn steamer trunks, kimonos, and random piles of household belongings, all left behind in April 1942 when Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 shipped thousands of Japanese-Americans from here to Idaho’s Minidoka internment camp.

In the early 1900s Nihonmachi had numbered 6,000 residents, but after World War II it never regained its stature, and the area became more diverse. This is one reason that on July 23, 1951, Seattle Mayor William F. Devin decreed a new name for the neighborhood—“International Center”—and praised, according to a Seattle P-I story at the time, “the mix of citizens of Negro, Japanese, Chinese, and Philippine ancestry.” (According to 2010 census numbers, 35 percent of Chinatown–International District residents are Chinese; 15 percent Vietnamese; 5 percent Filipino; 3.5 percent Japanese; and 2.7 percent Koreans and Asian/Pacific Islanders. The Caucasian population is slightly more than 20 percent; African-American, 15 percent.)

Despite this diversity, the name International District “implies we are one big happy Asian family,” fumes Betty Lau, a longtime teacher at Franklin High School and board member of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association, an organization established in 1915 to present a united voice for Chinese Americans in Washington state.

“Excuse me,” sniffs Chow, “we don’t all look alike. What we want to call it is Chinatown–Japantown–Little Saigon, because that’s what it is.”

“The Chinese here have always felt a slight when they hear it called the International District,” concedes Don Blakeney, who heads the Chinatown–International District Business Improvement Area.

Says Anita Woo: “This is Chinatown. Nothing more.”

“There has always been a tug-of-war here as to what is our cultural identity,” says Ron Chew, former director of the Wing Luke Asian Museum, named in honor of Luke, who in 1962 won a seat on the Seattle City Council—at the time the highest elective post held by a Chinese-American in the continental U.S. “I think of lot us believe that the happy medium was to call it the Chinatown–International District.”

The District has a history

of coping with disruption. The 1960s saw the construction of Interstate 5, which sliced through it, many older Asian-owned buildings demolished in its wake. Then in the ’70s, change came again when the Kingdome was built, then imploded in 2000 to make room for Safeco Field and CenturyLink.

“For a long time, the city never gave a shit about this neighborhood,” says Bob Santos, a Filipino-American who grew up in the NP Hotel in Japantown. “They put a freeway on the east side of us, and then they put the Kingdome on the west side of us. Now we’re surrounded by concrete.

“They wanted to put up a prison at Eighth and Dearborn, and we killed that. Some tried [in 2004] to put in a McDonald’s at Fifth and Jackson and we killed that. Now they got the street car that’s going to run down Jackson, and a spur line on Eighth that’s going to disrupt the neighborhood.”

Santos is not to be trifled with. Eighty years old, crusty, outspoken, and well-respected, he spent many years as executive director of the International District Improvement Association. Every Tuesday night, karaoke night, he closes down Bush Garden, belting out song after song.

He goes on, “We’ve been fighting a long time to preserve this neighborhood. After the Kingdome, we started building housing so people wouldn’t be displaced. We renovated the Bush Hotel. We know the old owners don’t want to renovate their buildings, but their children do.”

Santos believes good days are ahead for the International District: the expansion of Hing Hay Park, for one; the rehab and conversion being undertaken by Uwajimaya to remake the Publix Hotel into new market-rate apartments and active street-level retail space; and the $29 million affordable-housing project called Hirabayashi Place—named in honor of civil-rights leader Gordon Hirabayashi, who stood up against mass incarcerations of Japanese-Americans during WWII—which had a festive ground-breaking at the end of January.

“We have and will continue—Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and so—to retain our identity, our cultural values. We are proud of our heritage,” says Santos. “This used to be a 24-hour neighborhood. We need to get that vitality back again. This is the International District. That’s what I call it.”

“There’s a passing of the torch going on in the International District,” says Chew, who now leads the International Community Health Services Foundation, a clinic that each year serves 20,000 people speaking 50 different languages. “It is going to be up to the young here to keep the old Chinese businesses going. I just hope that we’ll be able to retain our cultural uniqueness.

“It’s not about freezing things in time, but about taking some elements of what’s special and making it fresh again.”

The Woos had hoped to get permission from city inspectors to allow me a peek inside their building, perhaps a glimpse even of the Wah Mee Club. But no luck.

Todd Matthews, though, in an act of pure serendipity, got to see the club with his own eyes. It was October 2011, and a production crew with Travel Channel’s Hidden City was in town to film a segment on the Wah Mee Club. “They contacted me for an interview, and I met them in Hing Hay Park,” Matthews recalls. “Shortly before we began filming, the host [Chicago crime writer Marcus Sakey] and I walked over to Maynard Alley and the Wah Mee Club.

“Now, the Wah Mee Club has been padlocked and off-limits to the public pretty much since the murders. I had seen photographs of the inside of the Wah Mee Club, both after the murders and in historic photographs from the 1950s, but I had never been inside myself. The doors had always hung slightly ajar, but they were held back by a thick chain and padlock.

“When we turned off King Street and headed down Maynard Alley, we were both surprised to find the club’s sealed double doors wide open. Standing in the alley, we could look inside and right into the club. There was a lot of junk stored inside the entryway, but we could also clearly see the curvy bar, the bar stools, a few folding tables, the steps leading down to the lower gaming area—everything! The host turned to me and said, ‘That’s pretty rare, isn’t it?’ I was stunned and said, ‘Yes, it is.’ ”

The fire all but extinguished the Wah Mee Club. The ceiling collapsed on what was once the bar area, while the wall in the basement under the club has buckled and brick has fallen from the center of the wall.

“It is too dangerous now,” says Timothy Woo. “But we want to bring it back, at least close to the way it was.” He means the building, not the club, for nothing in the nefarious gin mill will be restored or enshrined.

As Tanya Woo explains, “We want the community to move on and focus on the future.”