Artists belong to various different tribes and schools. There are painters, sculptors, and photographers; then the subdivisions sprout and branch into Pop, conceptualism, landscapes, figurative . . . The categories go on, ad infinitum. Where you belong depends on where you’re trained, what your medium is, and who your friends are. Gary Hill’s long career has landed him in the conceptualist/new media/video camp. His installations, prominently featured at the Henry two years back, explore language and perception, systems of meaning and sensory disassociation. Phenomenology, yes; glass-blowing, no.

Yet, as Hill explained during a recent conversation at his new show at James Harris Gallery, called ALOIDIA PIORM, he was unexpectedly invited to do a residency last summer at the Pilchuck Glass School. “I’m not a glass guy. It was pretty new to me,” says Hill, who recalls telling his hosts, “I’d be happy to come, but I didn’t want to make anything.”

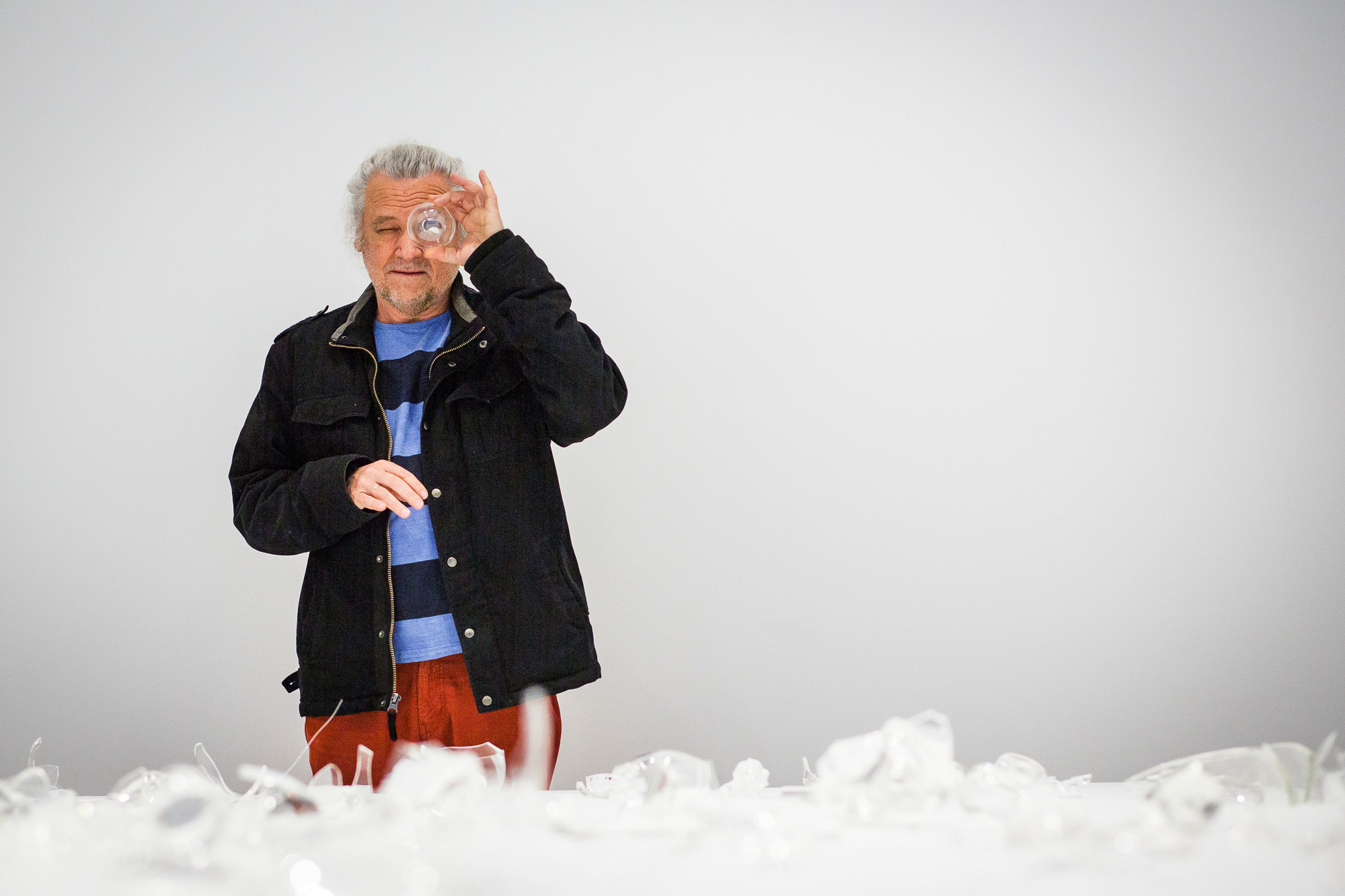

Instead he videotaped the making of one glass vessel, and now the video is projected into it, in a small piece called Klein Bottle With the Image of Its Own Making (after Robert Morris). The warped 2011 video projection Sine Wave, which some may also recall from the Henry, is also on view, but the show’s centerpiece is a collection of some 250 broken glass fragments and rejects from Pilchuck—essentially the refuse and mistakes made by student glass artists. This is ALOIDIA PIORM, the two titular nonsense words being among the made-up lexicon Hill devised to label each piece of glass.

“They have these recycling bins [of glass] that are normally melted down,” Hill explains. After gleaning the clear-glass scraps—spindly, blobby, sharp-edged, most of them palm-sized—he named them all in a few days. Some examples: Blonal, Choren, Golb, Vulphio, Noxu, Optax, Spoin . . . they read like Dr. Seuss rhymes or the sound-effect bubbles on the old Batman TV show. You could imagine them as alien words used in a cosmic Scrabble game on a distant planet.

How did Hill devise this dream-world nomenclature? “It’s a complicated process, a continuously varying system . . . a synesthesia system. There’s never a singular method.” Some terms he invented, others came via word-generation software.

“They’re not really names, because they’re not really words,” says Hill, “It’s toward naming.” Would he even notice if the glass fragments were moved by some impish gallery visitor and associated with different names? “Perhaps,” he says, sounding indifferent to the hypothetical problem. Of the semantic association between blob and name, he continues, “The more you look at them, the more convincing they become. They’ve been paired.” Pointing to one example, he asks, “How could that be anything other than a ‘Yoffa?’ ”

Rather than making glass art, says Hill, the process here is “sort of an undoing.” And when relating his fish-out-of-water experience at Pilchuck—where he also supervised the reproduction of a 20-year-old video installation, now made of glass and retitled Inasmuch as It Has Already Taken Place—Hill is careful to wag his fingers in air quotes when discussing, quite unseriously, “glass as a conceptual thing.”

Also prominent in the main gallery are two large and un broken vessels, created at Pilchuck under Hill’s direction, which depict the infamous atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima: Fat Man and Little Boy. Those names, so benign and almost comical, were invented by some forgotten scientist at Los Alamos. The association is arbitrary, as in ALOIDIA PIORM, but terrible.

A duplicate of Fat Man will be dropped and destroyed this Saturday in a public event (3 p.m., Rainier Oven Building, 1419 S. Jackson St., safety glasses required). The clear-glass bomb will be shattered into fragments, yielding pieces that would fit right in with those of ALOIDIA PIORM. Fat Man will be gone, its linguistic meaning erased and replaced with . . . what? Nam Taf? In this way, destruction becomes a kind of creation, yielding a new set of terms.

The drop will be filmed with a super-high-speed camera by Hill, who’ll then create a slo-mo video of their destruction. “It’s all about the anticipation of the fall of the bombs,” says Hill.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

JAMES HARRIS GALLERY 604 Second Ave., 903-6220, jamesharrisgallery.com. Free. 11 a.m.–5 p.m. Tues.–Sat. Ends March 1.