Christina Rock was 2½ years old when she first heard the word AIDS. She was playing in the sandbox at her Key West, Fla., apartment complex. A little boy was in there with her, surrounded by his toy trucks. Other kids played nearby.

Suddenly a stream of parents appeared, snatching their children away. An older boy hovering nearby, maybe 7 or 8 years old, filled Christina in. “We can’t play with you anymore because you have AIDS,” he said.

She was far too young to know what that meant. Nor had she any idea that her mother, a gaunt heroin user, had just tested positive for the disease, and that word had quickly leaked out at the complex, allowing the obvious implication to be drawn about Christina’s own status.

It was 1986—the dawn of the AIDS era—and the disease seemed both mysterious and unstoppable, spreading at a frightening rate from lover to lover, user to user, mother to child.

Her mother, teary when she picked up Christina up from the playground, didn’t explain. So all the 2½-year-old knew was that she wasn’t supposed to play on the playground anymore. She spent a lot of time indoors.

Over the next few years, her mother would die—although it seemed to Christina more as if the skeletal figure had just disappeared—and she started taking a pill, AZT, that sometimes left a bile-like residue in her mouth when she failed to swallow it.

But not until she was 5 did the word AIDS re-enter her life, again spoken by neighborhood children. Twin girls one day told her she had the disease. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Christina replied. The twins suggested that she go home and ask her father why she was taking medicine. So she did.

Her dad was furious. “We never say that word,” he told Christina. “We don’t talk about it. You have a medical condition.” That became the term he always used: Christina’s “condition.”

Whatever it was, it was serious. She understood that much. Around the same time, he told her that she was not expected to live past age 10.

Twenty-four years later, Christina Rock, very much alive, heard the news that a toddler in Mississippi had possibly been “cured” of HIV. Born with signs of the virus, the little girl had quickly been put on a regime using the latest medication, which she continued for 18 months. Then the child and her HIV-infected mother fell out of contact with their doctors. When they returned to medical care five months later, the child appeared to be free of the virus, despite the lapse in medication.

Amid the cautious optimism from scientists and the intense media interest around the world, Christina and a friend who also contacted HIV as a child decided to write an open letter to the ostensibly cured child. “Dear HIV baby,” they wrote in a blog post for the Staying Alive Foundation, an HIV-prevention initiative run by MTV. “We are hopeful that you will not have to know what it is like in the middle of the night to take HIV medications, to get kicked out of school, or have friends who will not talk to you because you have HIV,” Christina and Nina Martinez wrote. “But even if they do find that your treatment did not sufficiently make your HIV go away, we want you to know that you will still be okay.”

It was a message left out of all the breathy news coverage of a cure, which yielded the first big headlines about HIV and AIDS in years. Yet the okayness of people like Christina, contrary to every expectation when she was diagnosed, is at least as remarkable.

Today, Christina, a full-bodied woman with long brown hair, a sunny disposition, and a geeky side that finds an outlet in video games, lives with a long-term boyfriend who is HIV-negative. They have two young children, both of whom are free of the virus.

Medication has suppressed the virus in Christina’s body. And the regimen that accomplishes that—once nearly 40 pills a day—has gotten simpler and simpler. In April she started what she calls the “holy grail” of HIV drug regimens: one pill a day.

“It’s like a miracle,” says Matt Golden, director of the STD program at Public Health–Seattle & King County, marveling at the advances in HIV treatment. “There’s almost nothing in medicine that works as well as antiretroviral treatment.” Even diabetes, to which HIV is now sometimes compared because both diseases are chronic but manageable, does not have medication as effective, Golden says. “Oral treatments of diabetes and insulin work, but the reality is that a person diagnosed with diabetes at age 35 probably does not have a normal life expectancy.”

In contrast, he says that over the past two to five years, a growing body of research has shown that people with HIV on treatment can expect a normal lifespan.

The climate could not be more different from when Christina contracted the virus. Then, researchers had no drugs at their disposal, and so little understanding of AIDS that they didn’t know it was caused by a virus. Ann Collier, who in 1986 helped found the AIDS Clinical Trial Unit at Harborview Medical Center and today directs it, says she has gone from a time “when most of my patients died to a time when my patients are living full lives—having children, moving across the country for jobs.”

It’s a reality that not everyone wants widely known, for fear that HIV and AIDS will be seen as no big deal, unworthy of taking every precaution to avoid. “I’d rather have the image out that AIDS is a terrible scourge,” says Bob Wood, Golden’s predecessor at the county health department. As Wood points out, it is a scourge in many parts of the world, where poor access to health care and AIDS medication keeps the death toll high. Even though that is not the case in the U.S.—and implying otherwise would lead to the wrong impression about Wood himself, going strong at 70 despite having been diagnosed with HIV in 1985—he says, “I could live with that.”

Christina says she can’t. She wants people to know that people with HIV can still have a “wonderful life.” And she is part of a select group of people uniquely positioned to tell that story. As her doctor, Harborview HIV specialist Connie Celum, observes, we now have a generation of HIV babies who have grown up—“going through adolescence, becoming sexually active, making decisions about having children”—with the virus in the background the entire time.

Says Christina: “HIV is all I’ve ever known.”

Christina answers the door to her Bothell apartment on a late April day, her 29th birthday, wearing jeans, a ponytail, and a shirt resembling a poncho. Her 9-month-old daughter, Peyton, is taking a nap. Her blond son, Hayden, zooms around the apartment with the restless energy of a toddler but settles down to cartoons on the TV. She seems like any stay-at-home mom, except for the spare furniture that hints at the new life she is building here. In February, Christina and her partner Rob Walker, an information systems manager at Sharp Business Systems in Redmond, moved to the area from Indianapolis for Rob’s job.

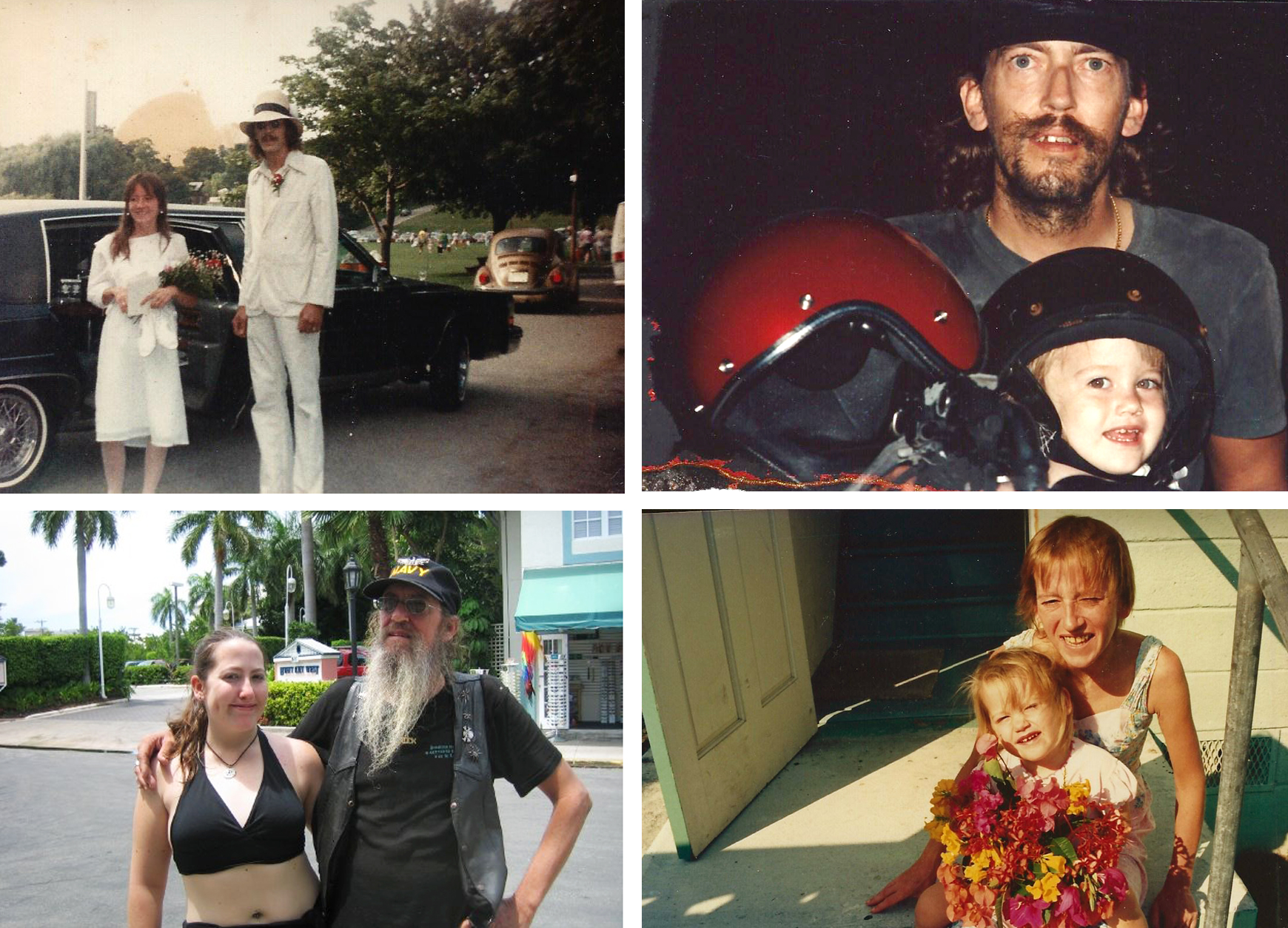

Settling into a seat at a table off the kitchen, Christina explains that her mother, Elizabeth, a onetime waitress, house-cleaner, and heroin user in Key West, probably got AIDS from a dirty needle. She goes to get some pictures of her mom. One shows a young woman in a jean jacket, her full, smiling face looking much like Christina’s. That was before AIDS. A later picture shows an ill woman with hollowed cheekbones and stringy hair.

Christina can barely remember her. A few months after Elizabeth’s AIDS diagnoses, she left for a hospice (or perhaps some other type of institution) and didn’t come back.

In the years that followed, living with her dad, Christina unwittingly began her own fight against HIV. Every few hours she had to take a dosage of AZT, even in the middle of the night. “There were always alarms going off in the house,” she recalls.

AZT came on the market as an HIV drug in 1987. In her Harborview office, the longtime AIDS researcher Collier explains what a breakthrough moment that was. “It wasn’t a cure,” Collier says. AIDS patients continued to die on AZT, she recalls, leading doubters to speculate that the drug, not the disease, was killing them. Yet to researchers like Collier, she says, AZT “was the first sign that you could make a dent in this virus.”

Even so, scientists’ understanding of AZT was limited. In the early days, Collier explains, they didn’t have a technique for measuring how much of the drug was in a cell, and they thought—incorrectly, it turned out—that a dose of AZT lasted only about four hours. Hence the constantly ringing alarm clocks at homes like Christina’s.

The regimen proved too much for some patients—including Wood, who had recently begun to head the AIDS program at the county health department. Wood recalls that he was part of an early AZT study run by Collier’s unit. “Then I got kicked out,” he says. The problem, he explains: “I would go skiing every January for a week or two, and while I was skiing, I didn’t like waking up to take pills.”

It was the nausea induced by AZT that Roy Arauz, a Seattle graphic designer and head of a small theater company called Arouet, couldn’t stand. “I never threw up so much in my life,” he says. After only about a week of that, he says, he decided to stop taking the drug. “I’d rather die,” he says he thought. But both he and Wood managed to stay alive until new drugs were developed in the mid-’90s.

Young Christina kept up the regimen, though. She says her dad told her she was “lucky” to have medicine, that dying kids in Ethiopia would “love” to have such drugs. “At one point, it gave me a complex,” she remembers. Guilt-ridden, she thought maybe she should pack up her medicine and send it to Africa.

Plus, her dad told her he sacrificed a lot to get her the medicine. He said he left his job as a cook at a Polynesian restaurant because it didn’t offer health insurance, and the only way to afford her pills was if they were on Medicaid. (She has relied on some form of government health assistance ever since. Even now, although she is insured through her partner, she uses the state’s AIDS drug-assistance program to pay for pills that cost more than $44,000 a year.)

It wasn’t until her teenage years that Christina began to rebel against the treatment. Ironically, she was taking far more effective drugs by then.

In 1996, scientists introduced so-called “protease inhibitors” that, when taken in combination with other HIV drugs, were a major step toward controlling HIV. The anti-AIDS “cocktail” dramatically cut the death rate. By 2001, Bailey-Boushay House in Madison Park, founded to serve AIDS patients with a nursing home and outpatient unit, started to see something new, according to executive director Brian Knowles: empty beds. Throughout the ’90s, by contrast, Bailey-Boushay’s 35-person nursing home typically had seen an AIDS patient die every day. Immediately, the bed of the deceased would be filled by someone on the waiting list.

Like AZT, though, the cocktail caused side effects. Collier ticks off a few: “nausea, diarrhea, numbness of the mouth.” So, she says, AIDS patients often had to take more drugs to counter those effects. In the end, many patients had a staggering number of drugs to swallow. Collier says, “That was when adherence became a huge issue.”

In high school, Christina says, she was supposed to take 39 pills a day, if you counted all the smaller tablets she would make from one chalky “horse pill” of a protease inhibitor called Videx that she couldn’t swallow whole. Seventeen pills in the morning, 22 in the afternoon: “I’d literally take one after another,” she says. “It was horrible.”

The grueling regimen and the nausea weighed her down. So, starting when she was about 16, she gradually opted out. “There’d be a day I felt I needed to not be sick. I had something going on in the evening.” So she skipped her pills that day. “I’d feel great.” Then she started to skip several days at a time, hiding the untaken medicine in baggies throughout her room.

Eventually she started to feel not so great. Home sick one day roughly a year later, she headed to the kitchen to make herself something to eat and passed out, falling downstairs and knocking out a front tooth. At the hospital, doctors took a T-cell count—a crucial indicator of HIV’s damage to the body since T-cells are vital for immunity. A count less than 200 earns one a diagnosis of AIDS. Christina’s was 74.

Even while all this was going on, HIV did not define Christina’s life. For one thing, she had other problems. Beginning when she was 7, she says, she was molested by a friend of her dad who lived with them. She believes he knew she had HIV. Because her dad had lost his driver’s license at one point, the man would drive them to Christina’s medical appointments. And yet he continued abusing her until she was 12.

Not long after, she told a school nurse that she wanted to leave Florida and live with an aunt and uncle in Massachusetts. She says she didn’t talk about the molestation, instead citing her dad’s overdrinking and pot smoking. Christina got her wish. In Massachusetts, she eventually told her aunt about the sexual abuse, which led to an investigation in Florida. In 2000 the man was sentenced to life in prison.

Given what she went through, she says she was “disgusted” by guys as a teen. So she wasn’t too distraught when her aunt told her that due to HIV, she shouldn’t have sex with anyone, ever. But like most high schoolers, she developed crushes. And at 15, a boy named Patrick let her know that he liked her too.

She waited about four months to tell him she had HIV. “We weren’t doing anything that would put him at risk,” she says. Still, she wanted him to know. So, hiking in the woods one day, she launched into what would become her standard speech of revelation, which went something like this: “You know how I said my mother died of pneumonia? Well, that’s true, but she that’s because she had AIDS.” Then she got to the bottom line: Her mother had passed HIV on to her.

“He was completely bawling,” Christina recalls. It wasn’t that he thought he might be at risk; he thought she would die. She reassured him as best she could and they stayed together a couple more months. When they broke up, HIV wasn’t the cause, she says. And she quickly found another boyfriend, telling this one about her status before they started dating. It wasn’t a big issue since they didn’t have sex. They stayed together 15 months.

In other words, despite HIV, her high-school dating experience was pretty run-of-the-mill. And that remained true even in college, when sex entered the picture.

She became a student at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell and recovered from the low T-cell count that had led to her AIDS diagnosis a few years earlier. (Unlike HIV itself, the immunodeficiency syndrome it causes can be reversed with modern medicine.) After her collapse, her medical providers had held a “come to Jesus meeting” with her, she recalls, explaining that since she’d taken her medicine only intermittently, the virus had developed a resistance to the drugs. Christina had to switch a whole new set of drugs. The upside was that the new regimen was less grueling, encompassing maybe 10 drugs a day. She took them, building her T cells back up, 10 or 20 a month, over the next few years.

Yet Christina often felt isolated at college. Administrators, declaring her the first student with HIV at the school, decided it would be better if she had a dorm room to herself, rather than sharing one as most freshmen did. Still, she reconnected with her old boyfriend Patrick, who was going to school nearby.

“At that point, I wanted to get it over with,” she says of sex. She practiced using a condom with a banana. He did some online reading about HIV. Otherwise, she says, “We didn’t overthink it too much.”

It would not be exactly right to say that Christina’s relatively normal dating life is typical of people with HIV. Christopher Tolfree, a psychotherapist who has worked for more than 25 years with HIV patients, much of that time at Seattle Counseling Service, says he’s heard “conflicting things” from his clients. Some tell him that potential dates, if HIV negative, “won’t have anything to do” with a person with the virus. “For others, it’s no problem,” Tolfree says.

Arauz, 45, has also seen it all. While single for a period of five or six years, the gay theater-company owner says, “I was turned down many times because I was positive.” He says he heard that when he walked into a bar, men would say “Oh yeah, he’s dirty.” He says that’s the way people talk about it: “clean” and “dirty.” “Please be clean,” ads on gay online sites will say.

Because of that kind of response, Arauz says he knows some HIV-positive people who only date others who are positive. In the early days of the virus, HIV professionals pushed so-called “serosorting” as the best way of containing it. The Cuff, a gay club on Capitol Hill, has long hosted “POZ” nights for HIV-positive men to meet each other. Arauz rejects that mindset as “marginalizing.” And despite the rejection he sometimes faced since being diagnosed in 1992, he has had two longtime partners who are HIV-negative, including the man he has now been with for six years.

Tolfree says that of late he’s been seeing more couples with mixed HIV status at Seattle Counseling Service. He adds that part of what reassures them is the new research that’s come out in the past couple of years.

He’s referring to a much-heralded study published in The

New England Journal of Medicine in 2011. Part of a long-term research project that is still ongoing, the study followed 1,763 couples of mixed HIV status—mostly heterosexual—in nine countries, many of them in Africa. The HIV-positive partner in half the couples received medication right away. In the other half, the positive partner got treatment only after the onset of certain symptoms—a delayed regimen that matched the treatment guidelines in many countries overseas.

After a little under two years, researchers recorded 28 HIV transmissions between partners. Only one came from a partner who had received immediate treatment. The conclusion: Treatment can reduce HIV transmission by an astounding 96 percent. Scientists and public-health officials could stop debating, as they often did, whether HIV treatment or prevention was more important. The study showed that treatment is prevention.

It was supposed to continue through 2015, relates lead author Myron Cohen, a professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina. But researchers knew they had to switch gears “as soon as we saw the results,” he says. A week later they stopped the protocol and offered all the HIV-positive participants immediate treatment.

“They were thrilled,” Cohen says. While the study had worldwide implications for treatment policies, for the couples involved it had a more personal relevance. Says Cohen: “People could have normal lives.”

This development would not have been fully realized had treatment researchers been satisfied with their breakthroughs in the mid-’90s. While they stopped getting the voluminous press that had heralded the death-defying protease inhibitors, scientists plugged away at making new and ever more powerful drugs. There are now nearly 30 HIV medications.

At the same time, researchers confronted the problem of how to make the multiple-pill “cocktail” more palatable. Their solution: combining several medications into one. The research took years. Each medication had to be tested first on its own and then in combination with other medications, explains Collier. In 2006 the FDA approved the first HIV combination pill, Atripla, to be taken just once a day.

Harboview’s Celum calls this medical advance a “game-changer.” Still, a number of longtime HIV patients couldn’t take Atripla because they had developed a resistance to one or more of the medications in it during the previous decades when adherence had been such a big problem. Christina, by then down to a handful of pills a day, says that was the case for her.

In 2011, another once-a-day pill came out; in 2012, yet another. It’s the latest pill, Stribild, that Christina resolved to try after moving to Seattle, starting up with a new doctor and discovering she wasn’t resistant to any of the Stribild medications.

On Friday, April 12, Christina took her first Stribild pill—a little nervously because she’d heard it could cause nausea or stomach problems. It didn’t. “Now I can almost pretend like it’s a daily multivitamin,” she enthused a couple of days later.

How do you talk about these developments? That depends, to some extent, on your generation, says psychotherapist Tolfree. “The older generation worked very hard to survive, to get people to buy into treatment,” he says. “If I’m 60 years old and I lost 80 percent of my friends and three partners,” he continues, then the news of a once-a-day pill does not suddenly make everything “hunky-dory.” He says anybody who suggests as much may find themselves faced with “anger and rage.”

Then there are the ramifications for public health. “I think it’s really important how we spin these things,” says Wood, the former health department official. That conversation has been going on since the early days of AIDS. Wood recalls that in 1994, when there was concern about health-care workers being exposed to HIV, researchers realized that a month-long course of treatment would dramatically reduce the chance of an infection taking hold. Harborview set up a program to deliver such prophylactic treatment, one that still exists today.

“But we decided not to market it,” Wood says, explaining that health officials were afraid that people would freely take risks if they knew they could use the Harborview program as a backup.

People started to take more risks anyhow after the well-publicized arrival of protease inhibitors in the late ’90s. The county health department’s STD clinic began seeing more gay men involved with multiple partners and having unprotected anal sex. The number of new HIV and AIDS infections in the county correspondingly bumped up at times over the ensuing years: Between 1999 and 2000, for instance, confirmed cases of either HIV or AIDS in King County rose from 328 to 445. New diagnoses, as well as sexual risk-taking, have plateaued since then. The county reported 276 cases in 2011, according to the health department’s latest epidemiology report.

“Above all, you have to be honest,” says Golden, the current head of the county’s STD program. That means the message about HIV has to be “more nuanced,” he adds. Even with normalizing treatment available, he says nobody wants a disease that requires them to take medicine for the rest of their lives.

Yet, rather than scaring people with now-outdated pictures of emaciated AIDS patients, his department is focusing advertising on encouraging people to get tested. The current “Find Your Frequency” campaign, run by the state and local health departments, including King County’s, asks people to determine how often they should get tested by considering what risk factors they might have.

Golden often meets directly with people who have tested positive, and it is then, he says, that he will stress the positive information, like the fact that they can expect a normal lifespan. “All those things you were thinking about doing, you should still think about doing,” he says he tells them.

Christina, however, says she feels that the dominant image of HIV is still overpowering, dread-inspiring negativity—one that she, unlike Wood, believes is bad for public health. She argues that if people think that HIV means they’ll never have anybody in their life again, that their life is essentially over, then they’ll be too scared to get tested.

So about 10 years ago, she started doing public speaking with an organization that seeks to portray uplifting messages about HIV, called Hope’s Voice. Only in recent years, however, has Christina’s life taken its most uplifting turn.

Rob Walker was an Air Force veteran studying for a Ph.D. in astronomy at the University of Oklahoma when he started looking for his half-sister, born after his parents had divorced and his mom had moved to Key West without him. Walker, talking over lunch one day near his office in Redmond, wearing a crisp white shirt, tie, and glasses, says he was worried about how his sister was faring in a city known for its drug and alcohol culture.

It was the beginning of the aughts, and Rob turned online to pursue his search. Through Yahoo! Messenger, he began to send inquiries about his sister to people whose profile said they lived in Key West. He came upon Christina’s. She was then living in Los Angeles and working as a technical writer, but hadn’t yet updated her profile.

Rob messaged her. She explained that she had moved, but offered to ask her dad, still in Key West, to look up Rob’s sister in the telephone directory. Rob and Christina started chatting online, and kept in touch after Christina’s dad found a number. She told Rob about living with HIV. The experience struck a chord.

“It wasn’t like I was an outcast growing up, but I wasn’t a super-popular kid,” Rob says. His mother’s departure, and what he says were her problems with alcohol and drugs, weighed on him.

Christina, who liked math and science, had always had a weakness for nerdy guys. When she said she admired the 13th-century mathematician Fibonacci, who developed a sequence of numbers mirrored in biological patterns, Walker confessed that he too was a fan. “That’s when I knew that I wanted to get to know him better,” Christina says.

Rob was interested, but held back. He says it wasn’t because she had HIV. Having done some reading and talked to a friend of his in medical school, he surmised that his risk of infection, should their relationship develop, was low if they took precautions—particularly since it’s less likely for a woman to pass HIV to a man than the other way around. What made him hesitate was their age difference: 12 years. He says he didn’t want to be the older man.

In the spring of 2009, after years of periodic on- and offline conversations, Christina decided to take a leap. A musician they both liked was playing in Indianapolis, where Rob had moved to be near an ailing grandfather. “Listen, no expectations,” she says she told him, “but if I fly in for it, do you want to go to the concert?” He did.

“It was completely awkward for about a minute,” she recalls. And then, she says, “it was awesome.”

As for HIV, Rob says, “We had talked about it so much for years. It wasn’t like it was the elephant in the room . . . Mainly I cared about her as a person, not about what disease she might have.”

They carried on a long-distance relationship for five months before Christina was laid off from her job in L.A. She moved to Indianapolis. There she and Rob faced a situation feared by every couple dealing with HIV: a condom break. Making the matter worse, Christina had been off her medication for a few months due to the move and the ensuing hassle of finding (and paying for) new medical care. She says she was so worried about infecting Rob that she’d forgotten about the more mundane potential consequences of a broken condom. But while the virus wasn’t transmitted to Rob, Christina did become pregnant.

She got back on medication pronto. Long before the groundbreaking study revealing treatment’s role in preventing transmission within couples, scientists had realized that HIV drugs radically reduced the likelihood of spreading the virus from mother to child. The 1994 discovery—by researchers at Seattle Children’s Hospital, among other places—has almost stopped the birth of HIV babies in the U.S. (although not completely, as the “cured” HIV baby from Mississippi shows). That’s certainly been the case at Seattle Children’s. According to infectious-disease specialist Lisa Frenkel, the hospital has seen no cases of mother-to-child transmission in nearly 20 years.

So the chance that Christina would replicate the story of her own birth by passing on the virus her mother had given her was slim. Still, she and Rob worried. “In the back of my mind, I thought something could always go wrong,” Rob says.

Doctors tested Hayden as soon as he was born in the fall of 2011. They found that the little boy did have HIV antibodies in his system, but that was normal for kids born to positive mothers. Christina could be expected to pass on the virus-fighting proteins. More important, the test found that he was free of the virus itself. To be safe, doctors gave Hayden a six-week course of AZT. They tested him again at two months and at 18 months—the last time definitively pronouncing him clear of HIV.

Christina, who has blogged on and off about her experiences with HIV, posted the news online. Rob says the post set off alarm bells with his parents, who were concerned that Hayden would be isolated if Christina’s situation was known. “I was really mad,” Rob says. “I told my parents, ‘I’m not going to teach my kids to be afraid of their mother.’ ” Nor, he says, was he going to make her HIV into a “huge secret.”

Rob has taken AIDS tests himself periodically. He admits that the first time, early in his relationship with Christina, he was “really nervous.” He got a clear bill of health, as he has every time since. And so his worries have faded, if not entirely disappeared. “I think about my kids,” he says. “We’re a single-income family. I’d hate to have something happen to me. But you know, I could get into a car wreck. That’s probably more likely than getting HIV.”

On May 1, Christina pushes a double stroller into a Bothell medical clinic. After Hayden, she and Rob decided to have another child, figuring that the risk from unprotected sex was low as long as Christina was on medication. The result: 9-month-old Peyton, who up until now has checked out as free of HIV. This morning, the baby has a routine well-baby visit, her first locally.

“Any particular issues or concerns?” the young, bespectacled doctor brightly asks, scanning the paperwork Christina has filled out. Christina brings up a little congestion that blonde, cherubic Peyton has been having. They discuss whether bronchitis might be an issue.

Looking back to the forms, the doctor then asks, in the same bright but matter-of-fact voice: “Who in the family has HIV?”

Christina raises her hand. “I assume you were on antiretrovirals when you were pregnant?” the doctor queries. Christina indicates she was, and fills the doctor in on the HIV tests Peyton has taken so far.

The entire HIV discussion lasts about one minute. “All right,” says the doctor, turning to the computer. “I’m going to take a peek at the growth chart here.” Then they discuss Peyton’s healthy size, her babbling, her ability to crawl and grasp at toys, and a benign pink mole on the her forehead. The doctor looks Peyton over on the exam table.

“All good, my dear,” she says, gently lifting Peyton up. “She looks great!” she reaffirms to Christina. And then, the sun blazing outside, Christina takes the kids to a playground.