MICROSOFT’S LATEST earnings report was certainly comforting news to shareholders who have watched other tech firms tank. Annual revenue of $32 billion, up 13 percent year to year. Not to mention a handy $10 billion profit and $49 billion in petty cash. But hidden beneath the heady numbers lurks a nagging question: Are there limits to Microsoft’s success? The question might seem nonsensical if you don’t look beyond the core operating-system and mainstream productivity-software businesses. On the personal computer, Microsoft rules with more than 90 percent market share for both desktop operating systems (various flavors of Windows) and the combination of standard word processing, spreadsheet, and presentation programs in its Office suite.

Yet Microsoft has trouble whenever it tries to grow outside of this core competency. The failures are “disappeared” from Microsoft’s official history with an efficiency that George Orwell would have admired.

TAKE THE CONSUMER market. In 1993, Microsoft hoped to appeal to the masses of “multimedia PC” buyers (that is, PCs with both a CD-ROM drive and a sound card, revolutionary at the time) by introducing a line of software called Microsoft Home. More than 100 products were launched in rapid succession over 18 months, from childhood creativity (Fine Artist) to a cartoony “social interface” to make Windows appear friendlier to the pathologically computer phobic (1995’s Microsoft Bob, a much-maligned happy face with geek glasses). Microsoft quickly discontinued more Home products than most other consumer software publishers released, and the brand itself eventually disappeared. The Encarta Encyclopedia was one of the few titles to successfully leave Home alive.

Subsequently, Microsoft tried its hands at toys, introducing the ActiMates line of interactive plush in 1997. The toys reacted by talking and moving, especially when wirelessly activated by a software program or TV show. But after three holiday seasons of touting ActiMates Barney, Arthur and D.W., and the Teletubbies, the Disney audio-animatronic wanna-bes were quietly shown the off switch.

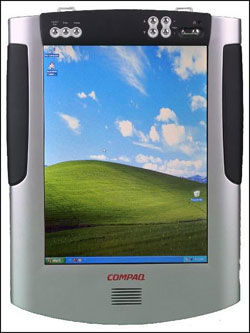

Many of Microsoft’s business-oriented initiativesthe ones that weren’t destined for the desktop PChaven’t fared much better. Microsoft at Work, an effort to embed Windows into copiers and other office machines, failed miserably. So did Microsoft’s initial forays into portability: WinPad (handheld PCs) and Windows for Pen Computing (pen-based tablet computers).

MORE COMMON than outright failure are efforts that are never officially abandoned but continue to limp along or are adapted for other products. Slate, one of the pieces of Microsoft’s dot-com-era aspirations that included adventure travel site Mungo Park and the Sidewalk city sites, survives. Microsoft is trying to revive its eBook initiative with a 20-week promotion, giving away three eBooks each week. Even the cutesy cartoon assistants in Microsoft Bob made their way into Microsoft Office 97.

But some observers say Microsoft’s biggest failures are still in progress. And they’re in Microsoft’s once high-profile hotbeds of smart mobile phones and interactive television, neither of which has gained traction among major customers or the marketplace.

“Microsoft tries to do all things for all people in software. As you scale down devices, it tends to overload them with too much software for what people need,” notes Dwight Davis, vice president and practice director for tech analysis firm Summit Strategies and one-time editorial director of the Microsoft-centric newsletter Windows Watcher. Davis points to Microsoft’s mobile- phone software efforts as a train wreck in the making: “By contrast, I think their long-time foe Java is moving much more rapidly and successfully in that market.”

Microsoft’s Smartphone initiative took a hit late last year when U.K. handset maker and longtime Smartphone supporter Sendo abruptly dropped the Microsoft operating system for one made by a rival. And last month, RealNetworks outflanked Microsoft to supply video streaming capabilities to Vodafonethe world’s largest mobile phone company and part owner of Verizon Wireless. In an almost prescient move, before the Vodafone news broke, Microsoft renamed its Smartphone software Windows Mobile, combining it with its more successful Pocket PC operating system under the new moniker.

MEANWHILE, MICROSOFT’S nearly-decade-old interactive television initiatives continue to falter. “I think Microsoft’s biggest failure by far is the series of investments they made in cable companies all over the world,” says Steve Wood, Microsoft employee No. 6 and now president and CEO of Wireless Services Corporation. “The idea was to leverage those investments into customers for their set-top and interactive-entertainment platforms. I don’t think the leverage worked in even one instance.”

MICROSOFT CONTINUES to plug away. In June, Chairman Bill Gates promised the annual National Cable & Telecommunications Association trade show that the new Microsoft TV Foundation Edition will let cable operators deliver advanced digital TV features like video on demand with existing hardware and networks. And the company announced that, in Seattle, Comcast customers will test the technology.

There seems to be a common reason for Microsoft’s missteps in TV and telephones: a lack of understanding of how non-PC businesses work and a desire to impose Microsoft’s vision upon both. “Their method of operation has often been ‘take no prisoners.’ The telcos and the handset manufacturers are certain they don’t want this fate to befall them,” adds Davis.

Still, Microsoft has had successes. Its mouse and keyboard business is highly regarded for creating innovative products, from the ball-less IntelliMouse Optical to the odd-shaped yet comfortable Natural Keyboard. Other successes were born less out of innovation than sheer determination. The new server version of Windows for corporations, Windows Server 2003, evolved from Windows NT and Windows 2000 and is lauded by Davis as “an enterprise-grade operating system without too many qualifications.” Two Microsoft corporate server applications, Exchange Server for e-mail and SQL Server for databases, likewise have established themselves. Research firms Gartner and IDC both place Microsoft SQL Server as a fast-growing third behind databases from Oracle and IBM. “They’ve done a really brilliant job in leveraging their strengths in the desktop operating system and applications and tying it to the server,” says Davis.

Microsoft is trying to expand from this business beachhead. Over the past two years, it paid $2.4 billion dollars for Navision and Great Plains Software, adding high-end business management, customer-relationship management, and accounting software to its offerings.

Microsoft also continues to pour money into high-PR-value efforts it hopes one day will be profitable. Xbox wrested the No. 2 video-game console position (behind Sony PlayStation 2) from Nintendo’s GameCube in the U.S. and Europe and has sold more than 9.4 million consoles worldwidemore than forecast. MSN is the No. 2 Internet service provider behind America Online with 8.6 million subscribers and, as Microsoft noted in its earnings comments, “solid advertising growth.”

And don’t forget that Microsoft is a player in media (MSNBC), Wi-Fi hardware (Microsoft Broadband Networking wireless adapters), consumer electronics (Web TV’s evolution into MSN TV, and the forthcoming Smart Personal Objects Technology watches from Fossil and Citizen), andagainpen computing (Tablet PC).

IT ALL MAKES DEFINING Microsoft today a challenge. The exercise can lead to as many descriptions as there are definers; it’s enough to make a Redmond brand manager blanch. And that might be at the heart of Microsoft’s biggest obstaclenot antitrust woes, not the free Linux operating system, not open-source competitors to Office. “Microsoft’s biggest challenge is its size, its cross-matrix structure, and constant reorganization,” says Pam Miller, a public-relations executive and former PR consultant to Microsoft. “The company thrives on chaos, which served them well in its early days. But as the company has matured, it seems more like a conditioned habit that’s difficult to overcome and makes it difficult to innovate.”

Wireless Services’ Wood agrees: “When you can’t afford to spend time on a product area until you are convinced that the market opportunity is at least $100 million a year, you are going to be late in understanding any truly new opportunities.” Microsoft repeatedly has handled this by acquiring innovative companies. But as Microsoft grows, assimilating new ideas and rapidly acting on them becomes more difficult. Even Microsoft identified “executing with excellence on multiple fronts” as a key business risk in the discussion of its annual results.

Microsoft ultimately might become a prisoner of the industry it helped create. Much like IBM, the earlier leader in computing that Microsoft trumped in the 1980s, Microsoft’s fate might be as tied to personal computers as IBM’s was tied to mainframes.

Frank Catalano is a tech-industry analyst, consultant, and author. He can be reached via www.catalanoconsulting.com.