BACKSTAGE AT OZZFEST a few weeks ago, a crew worker with a David Lee Roth glint in his eye nudged me and asked how I got my backstage pass. Irritated by his Cro-Mag assumption, I went over in front of the Methods of Mayhem tour bus. Admittedly, this was not the brightest move if I was hoping to avoid a similar encounter, since Tommy “Pam-Just-Left-Me” Lee probably lurked inside, but what I didn’t anticipate was walking into a scene straight out of 1985: A group of sweet-faced young girls, cooing like a flock of hormonally wired doves, banged ever so saucily on the bus’ windows. The ringleader, complete with flaxen curls and pink satin hot pants, was a dead ringer for Heather Graham’s Rollergirl character in Boogie Nights. When men acknowledged the girls with catcalls and whistles, Rollergirl pouted, sucked her pinkie demurely between her sparkly lips, and stuck her satin-swathed ass out at such an extreme angle that I feared several vertebrae would pop from the strain.

While hardly unprecedented (hell, even VH1 has a “Where Are They Now?” for groupies from the ’70s), these regressive roles for men and women in rock music are currently enjoying a hearty, head-spinning, and ultimately disturbing comeback. In a New York Times article last summer, esteemed music critic and unapologetic feminist Ann Powers responded to the unsettling reports of rape and vicious, misogynistic behavior that surfaced in the aftermath of that summer’s disastrous Woodstock festival. Citing the growing popularity of lyrically aggressive and sonically thick-headed bands such as Kid Rock, Limp Bizkit, and Blink 182, Powers observed a revival of the boys-only club. Not only were these boys back in testosterone-fueled force, she warned, women were welcome to join in the mayhem—as long as they played by certain rules.

“At these shows [Woodstock ’99 and the Warped Tour], women screamed their adulation for the very stars hurling invectives at them,” Powers wrote. “They climbed the shoulders of their male companions and waved to the throng waiting to grope them. The women seemed to be reviving the role of the old-fashioned rock chick, who gained the right to be sexually expressive by running a gantlet of degradation and scorn. And the men were all too ready to debase them.”

Post-Woodstock media coverage glossed over most of the sexual assault reports, and only a few male voices sounded their objections, most notably the Beastie Boys and techno-Cassandra Moby. In an interview published by Addicted to Noise, Moby said, “I think the mistake they made was in hiring misogynist rock bands. If you have all these aggressive bands together, it’s a lowest-common-denominator situation. I think 99 percent of the problem was the bands that they chose to perform there. I wasn’t familiar with most of them before I got there. I watched ICP [Insane Clown Posse] in open-mouthed horror. This is what Kurt Cobain died for? So these redneck idiots can be rapping about bitches and telling women to take their clothes off?”

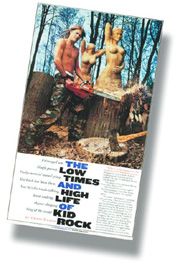

By the end of 1999, it was clear that a vicious strain of sexism was once again standard outfitting for mainstream rock’s biggest male stars. Virtually every artist Powers mentioned in her article had taken up residency on the Billboard charts as the year came to a close. Strutting and preening like a date rapist on an after-school special, Kid Rock appeared on Saturday Night Live with two buxom blondes. The women gyrated robotically, as if they were in an ’80s glam-metal video. To add implied injury to insult, the lead photo in his June 22 Rolling Stone interview depicted Rock wielding a chain saw, preparing to sever a wooden statue of a female figure. Rock’s antics, though, were soon overshadowed by the stratospheric rise of what Salon.com has called the “most violent, woman-hating, homophobic rapper ever”—Eminem. Disputing Salon’s claim is nearly impossible, regardless of his work’s artistic merit; phrases such as “all bitches is ho’s, even my stinkin’ ass mom” and “hate fags? the answer is ‘yes'” aren’t exactly open to multiple interpretations.

BOY POWER

Yet young women, in my experience, interpret male rock icons more freely—that is, until this new bad boy showed up. Not so long ago, the glam-rock guitar hero was a more flexible signifier for female fans. He stood for all the other, less famous boys in our day-to-day lives, and that gulf made us question our misplaced deference outside the concert arena. Our rock heroes’ amped-up confidence also helped inspire what Seattle musician and author Vanessa Veselka has dubbed the “macha quotient,” the degree of feminine self-determination in our developing self-image.

Arriving at the age of 30 along the dual trajectories of punk-rock feminist theory and an inexplicable and undying love for ’80s heavy metal, I can easily attest to the gender awareness that women bring to their experience of rock music. As a teenage girl, I never had any interest in becoming a groupie or band “ornament” (the self-given moniker of Jim Morrison’s wife Pamela), and, with the exception of a perpetual fascination with xylophones, I never had a burning desire to play music myself. I was far more intrigued with the angry, self-righteous, and seemingly invincible persona the testosterone-infused music invoked. Even at an unquestionably naﶥ period during my adolescence, I was aware that the rush I felt watching Dave Lombardo drum or Cliff Burton play bass was a step closer to the power and status of masculine energy, and the social advantages that came with it.

While many of my girlfriends huddled happily for hours outside tour buses, their toes scrunched into red pleather boots and hair feathered to sky-scraping heights, I fantasized about harnessing heavy metal’s macho power and commanding the intellectual attention of my male classmates. This is not to say that I didn’t accept plenty of the weak female stereotypes hurled at me; even as I was accepted into the boys’ club, I assumed the passive role assigned to me and my sex. I dressed the part, and I spent way too much time wishing I could get a gig as one of those ZZ Top girls or as Prince’s next muse. Although I would occasionally tap into the strength I felt boy-rock energy gave off, I couldn’t fathom viewing something female as strong. Consequently, at the ripe old age of 17, I was certain that feminism was something represented by “a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle” T-shirts, angry lesbians, and all things patchouli-scented.

I was not alone in my beliefs. At the height of Reagan-Bush conservatism, Paula Kamen documented the endless excuses women gave for eschewing the women’s movement in her 1991 book Feminist Fatale. From their perspective, most of the major battles had been won: Abortion rights and access to birth control, the right to vote, access to the job market, and continuing education were seemingly secure. It was too man-hating, too hippie, too hairy, too irrelevant.

GRRRLS AND GUYS 2-GETHER

Shortly after Kamen’s analysis was published, Naomi Wolfe (The Beauty Myth) and Susan Faludi (Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women) struck huge chords for neo-feminism, a political and pop-cultural rebellion that quickly gained momentum. This Third Wave converged with a revitalization of punk rock as both a musical genre and as an ethical and creative stance, subsequently paving the way for a pro-woman, anti-homophobic landscape in pop music—and the Riot Grrrls.

Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill connected with grrrls across the country via a surprisingly efficient network of self-published ‘zines and led a fiery, do-it-yourself collective of feminists based in Olympia, Washington, to shatter stereotyped gender roles and have their say. Hanna’s disciples began picking up instruments en masse, and bands such as Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, and Huggy Bear issued a call for “revolution grrrl-style NOW!” that echoed all the way from DC to London. Debbie Stoller and Marcelle Karp launched BUST magazine (“for women with something to get off their chests”) in July 1993, a pro-sex, grrrl-culture journal that prides itself on expressing the “voice of the new girl order” and chronicling women’s experiences and opinions.

Because punk aesthetics were again being embraced, so were punk ethics, including egalitarianism. Not only were women making significant strides through their own cultural activism, they were forming allegiances within the male-dominated world of rock: Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder, the two most prominent front men at the time, vocalized their intolerance for sexism and their support of contemporary feminist concerns. For example, Cobain made the following plea in the liner notes to 1992’s Incesticide: “At this point I have a request for our fans. If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us—leave us the fuck alone! Don’t come to our shows and don’t buy our records.”

Vedder closed Pearl Jam’s MTV Unplugged set by scrawling “pro-choice” on his arm; he met with Gloria Steinem to discuss violence at abortion clinics and talked with Sleater-Kinney and Home Alive about women’s self-defense issues. Cobain and Nirvana bass player Krist Novoselic helped coordinate benefits for Bosnian rape victims and actively supported the Riot Grrrl movement by taking female bands with them on tour. “We were outright in our support of gender and same-sex equality issues,” Novoselic recalls via e-mail. “Nirvana brought the ethos it learned from the punk rock scene of the early ’80s into the mainstream rock movement of the early ’90s. I am proud to have been part of the music known for a certain progressive consciousness. . . .”

Novoselic also cites Nirvana’s politically conscious stance as a reaction to the intolerance that he sees as continuing to permeate the white middle class. “Nirvana was attracted to this ethos because of the social conditions around us. These conditions weren’t inherent in southwest Washington exclusively; they are inherent in our culture today, even in progressive Seattle. Obviously we were repelled by redneck, macho posturing. But equally repulsive is the indifference to sexism and homophobia found in the comfortable, nice, and safe working-middle-class society we come from.”

Pop culture crushes one trend in order to make room for the next one, and never has this been more painfully evident than in the premature demise of the punk revival and Riot Grrrl. Regurgitated back to middle America were the platitudes of “girl power,” as well as an eventual avalanche of watered-down, safely marketable Nirvana and Pearl Jam clones. As Cobain was the most recognizable presence in the convergence of neo-punk and Third Wave feminism, his suicide can arguably be seen as a troublesome indicator of this repackaging of extreme gender roles within the music industry.

SLIM TRENDY

And as unnerving as the second coming of the knuckle-dragging misogynists is, what’s even more disheartening is that the pop stars brandishing two X chromosomes have reinforced an equally cartoonish extreme. While undeniably powerful, sexist attitudes have difficulty flourishing in the presence of high-profile, strong, and articulate female icons. But the best-selling and most visible “women” in music right now are buxom, blonde, pubescent Barbies/Lolitas with bare midriffs who seem to believe that what a girl wants is to be hit one more time—if not literally, than at least by a force far greater than she herself can control.

Meanwhile, many of the Third Wave’s key players are still actively making music, but they aren’t topping the charts: PJ, Courtney, and Tori have been nudged aside by Britney, Christina, Jessica, and Mandy. It might seem odd that the same teenager who plunks down his allowance for Slim Shady’s latest release is also snapping up Oops, I Did It Again, but in reality the two extremes are mutually dependent upon one another’s reinforcement of negative, yet complementary, stereotypes. Even a brief perusal of CDNOW’s “Album Advisor” or a peek into an MTV.com chat room shows that they’re sharing the same fan base.

Despite the overheated cheerleading of the Spice Girls (or perhaps because of it, as BUST editrix Debbie Stoller suggests), most girls on mainstream pop’s radar are not themselves in possession of a great deal of power. As always, the indie underground holds an empire of ass-kicking women, but the average 12-year-old girl is much more likely to get her hands on a “Born to Make You Happy” Britney Spears doll (visit britneyboutique.com if you doubt this exists) than a CD by LeTigre (Kathleen Hanna’s new project).

Between the threat of sexual assault in the mosh pit and the benign musings of Jessica Simpson, women are getting a phenomenally raw deal—show us your tits, sing sweet songs of complacency, or just give us a blow job and get out of our way so we can, as Limp Bizkit Fred Durst encourages, “break shit.”

Why are fans so receptive to these retrograde icons? I took an informal poll at the after-party for the Up in Smoke tour (featuring Eminem, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dog), and not one of the partiers could give a lucid response. (And don’t blame the dope, since they were able to converse coherently on other subjects.) Many cited Eminem’s supposed “honesty,” as if his calculatingly stage-tested, chart-topping lyrics were torn directly from his personal diary or psychiatric file. More disturbing was that almost everyone defended his slurs by insisting “He doesn’t really mean it,” which precisely contradicts the prior defense—you can’t have it both ways, kids.

However, kids’ need for this dichotomy may be amplified at a time in history when the pace of nearly everything in their environment is accelerating at an eye-watering rate—from communications technology and the globalization of the economy to violence among their youngest peers—and a lot of kids feel they are being left behind or simply disregarded. Sadly, it’s this need for extreme, cartoonish duality that is creating the perfect platform for the gender caricatures we’re now faced with.

Spend some time around a bus stop when your local high school lets out—you won’t have to wait very long before you see young girls referring to each other as “ho’s” and “bitches.” This isn’t any sort of subversive reclamation of a negative term; too many of today’s young women are unquestioningly swallowing negative or narrow ideas about their gender. Their vocabulary reflects how they view themselves.

In a music industry that profits from marketing gender roles and stereotypes, male rock icons can be shockingly accurate depictions of our culture. Even as women gain ever greater equality by the standard benchmarks— income, education, opportunity—this new macho posturing speaks to a backlash against recent feminist advances. The concert stage gives seeming license for the rhetoric of male resentment that isn’t uttered—one hopes—in the classroom, boardroom, or home.

Unsurprisingly, then, the harshest, most offensive speech is coming from those men left farthest behind in our dot-com growth era. Eminem and Kid Rock are only the most notorious examples of poor white trash seeking refuge in the old certainties—i.e., inequalities—of gender roles. Others will follow. But if they’re any indication of where the music industry is headed, women who love rock ‘n’ roll should think twice before they put another dime in that jukebox.

And if women start listening closely to the music, maybe they can bend a few sympathetic male ears to the cause. The current cycle of sexism in pop music may only require a little more scrutiny to go bust. Eminem himself stated following the recent MTV Video Music Awards that he’s about to hit his high-water mark, and Kid Rock exhibits all the qualities of a future Vanilla Ice (I’m just waiting for Weird Al to write “American Dumb Ass”). Just as the neo-punks and Riot Grrrls helped stigmatize sexism and greed in the ’90s, our current icons are going to eventually have to deal with an equally formidable response to their misogyny. Says Novoselic, “Cynicism and indifference are so trendy. If people are indifferent to the messages on the CDs, I bet they’ll be indifferent to the music and artists soon enough. How can they be endeared to that stuff? I bet they’re not paying attention.”