Supermensch

Opens Fri., June 13 at Seven Gables. Rated R. 84 minutes.

The subtitle of Mike Myers’ first film as director is “The Legend of Shep Gordon.” If this were a comedy feature, and it’s not, he’d play the titular role: a hearty Jewish tummler who smoked dope with—and sold it to—all the L.A. rock stars of the late ’60s, then switched to managing them; partied with them; bedded many beautiful women; did lots of drugs and alcohol; produced movies; dated movie stars; and even bought beachfront Maui real estate when it was relatively cheap.

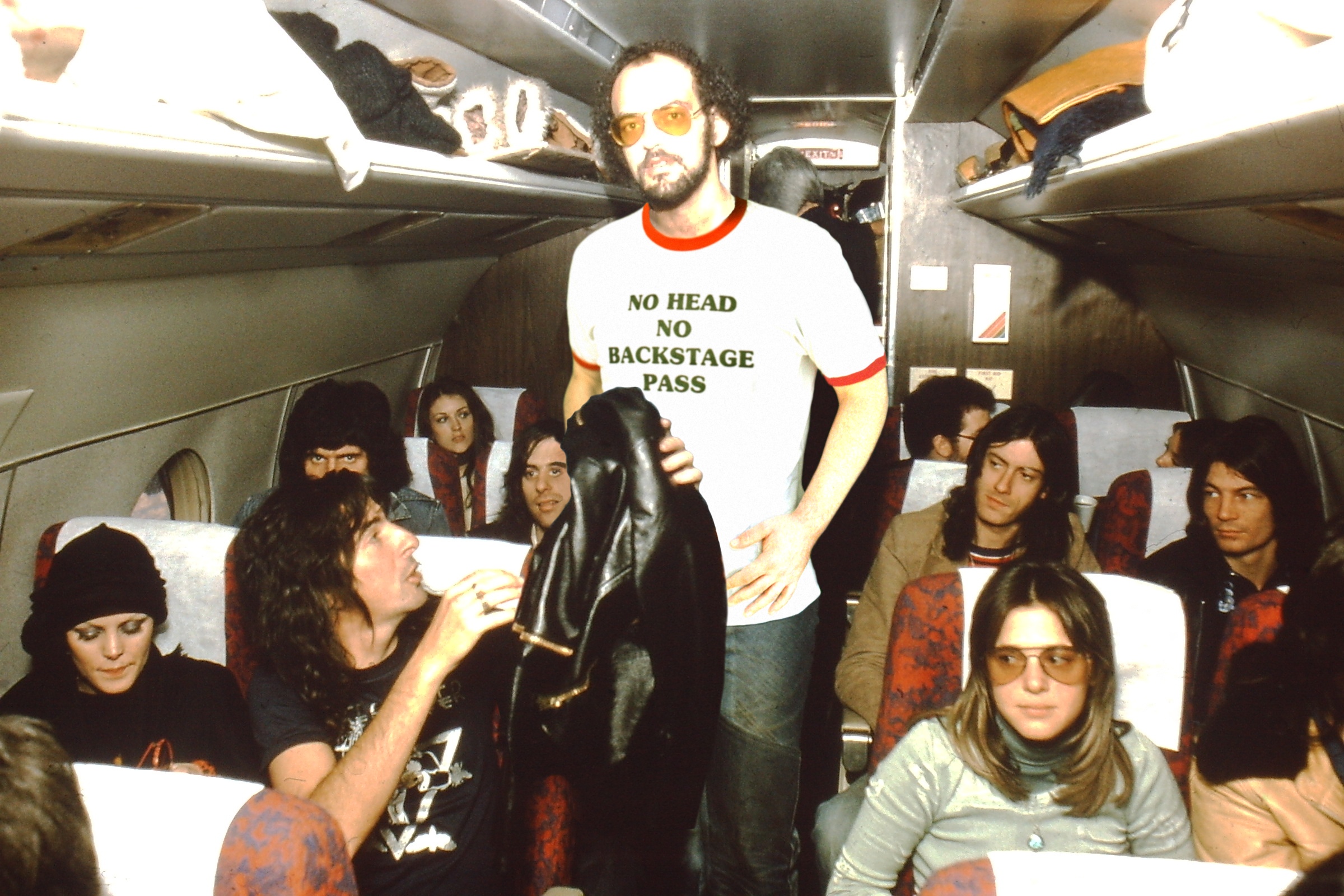

Today, it’s good to be Shep. He’s rich, largely retired, loved by everyone who, like he, somehow lived through the hedonism of that golden age. He can look back on past excess with the contentment and good karma of a life well-lived. Avuncular and incredibly well-connected in Hollywood, Gordon hobnobs with the Dalai Lama, Michael Douglas, Sylvester Stallone, Willie Nelson, and a host of other celebs. Myers harvests plenty of their A-list praise and logrolling for his friend, now 68, who relates his old debaucheries with only mild embarrassment; he’s lived long enough to laugh at shenanigans at the Playboy Mansion and on the chartered plane of his first and most loyal client, Alice Cooper. (Scenes of the two buddies playing golf—Cooper without fright makeup, dyed hair tucked neatly in his cap—suggest some sort of reality TV show.) As the accolades keep rolling in, however, and as we better appreciate Gordon’s gilded life, the doc becomes poshly self-congratulatory and repetitive. Winners, no matter now nice, become dull after they’ve won. Money softens all the edges and ambition.

It’s the louche, ’70s side of Gordon’s rise that we want to see—and that’s plainly the movie Myers wants to make. From Wayne Campbell to Austin Powers and even to, groan, the Love Guru, he’s always had a backward-looking reverence for his showbiz forebears—all those guests on the Johnny Carson show that he, growing up in suburban Canada, longed to join. Shrek has made him rich since his early-’90s success, though Myers here speaks on camera of “a very hard time” (alcoholism? divorce?) when Gordon sheltered him. This film is partly the repayment of a heartfelt karmic debt to Gordon, whom anyone watching would want to have as a friend (especially given his open-door policy toward Maui visitors). It’s also the outline for a script that, after Gordon’s death, Myers might eventually film—with more misbehavior and less serving tea to the Dalai Lama.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com