For four years, antiracist organizers have labored to prevent the construction of a $210 million King County Children and Family Justice Center that would include jail beds for more than a hundred children. Their efforts were dealt a blow just before Christmas when the city planning office gave the project a green light.

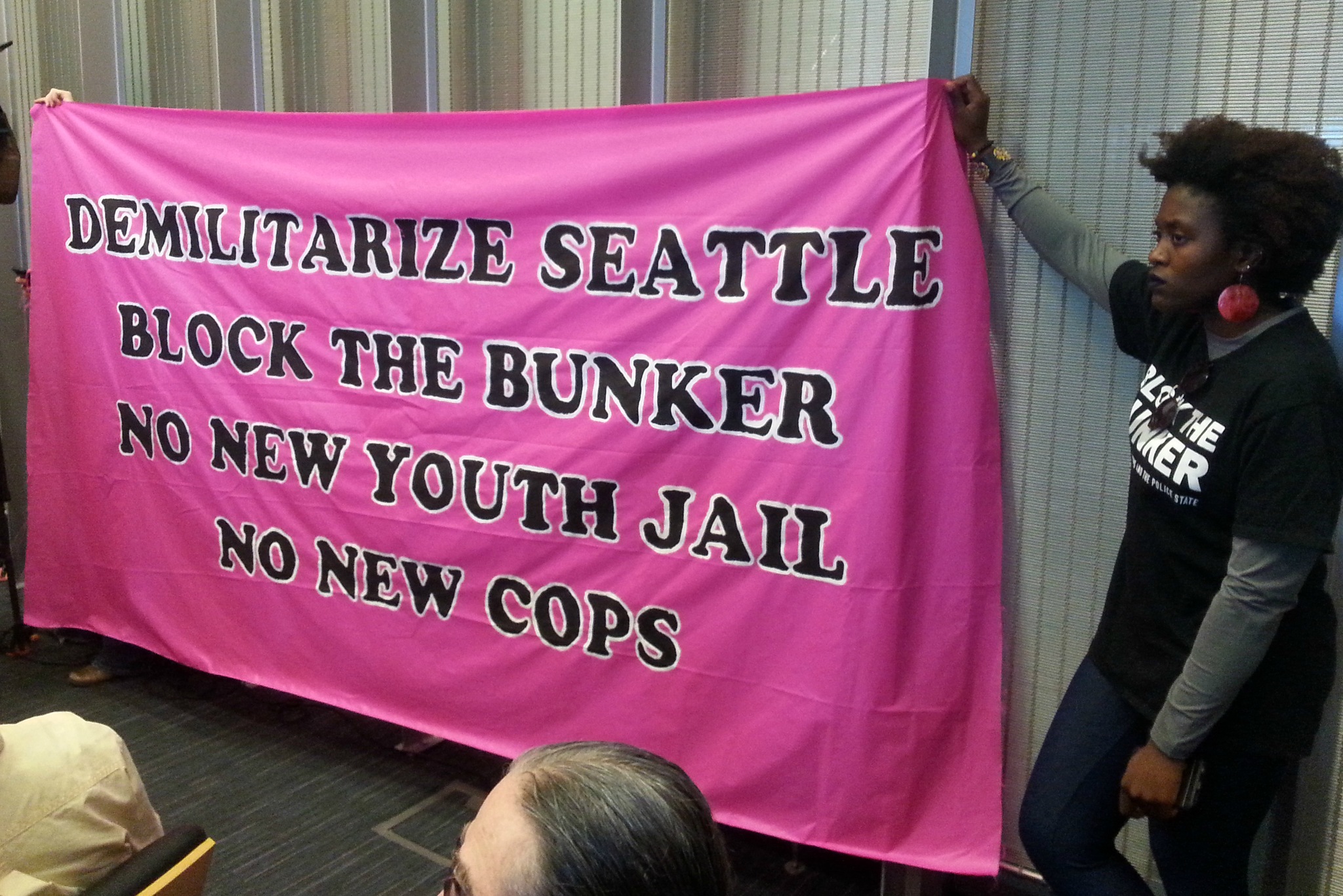

But the activists are hardly done fighting. While city officials cast the recent planning approval as a mundane bureaucratic step in the process, it has brought the fight back to the fore, with opponents of the plan staging protests and laying out their game plan for 2017.

The strategy is twofold, according to Senait Brown, a longtime activist with Ending the Prison Industrial Complex (EPIC). “Seventy-five percent of our energy is building community-led alternatives,” she says, with the goal of replacing rather than reforming the current model of youth justice. For example, EPIC and fellow travelers convinced the city this past year to launch a pilot program in which prosecution in court is replaced with “restorative justice circles” where offenders and victims have a facilitated conversation.

“What’s happening in 2017 is a continuation of what happened in 2016 and 2015,” says Brown. “Folks have been spending the majority of their energy … building antiracist, black-led community alternatives to juvenile incarceration”—in other words, give poor black communities most affected by youth incarceration direct control over the mechanisms that address youth misbehavior. “We have the solutions, we’ve been funding the solutions, we’ve been creating the solutions that we want to see and that we know work,” says Brown. “We want to see community-led, community-owned responsibility for our own children.”

EPIC also plans to continue lobbying elected officials to kibosh the youth jail. They’ve already had some success by convincing planners to reduce the number of beds. And according to King County Executive Services spokesperson Alexa Vaughn, the 112 beds still planned are all convertible into non-jail purposes. “We have more in common than we have that separates us,” Vaughn says. “Both sides of this issue want to see juvenile detention reduced whenever possible.”

Brown says she hopes the County Executive and Council “make a better choice, but I also know that kind of change doesn’t come from inside an institution.” Instead, she says, it comes from young leaders like the ones EPIC organizes.“We’re open to having continuing dialogue with [King County Executive] Dow Constantine and giving the support that he needs to be able to see the opportunity that’s in front of him right now,” she says. So far that dialogue has included innumerable packed, often rowdy public meetings, including a recent “Hate Free Zone” speech-a-thon that was supposed to be about unified progressive opposition to president-elect Trump but which a contingent of surprise protesters managed to make about the youth jail. During the holidays, dozens of jail opponents protested outside Mayor Ed Murray’s house.

The campaign against the youth jail has been ongoing since voters approved its funding in 2012. In February 2015, hundreds of people packed the King County Council Chambers inside the county courthouse to protest the council’s vote to approve the project. That spring EPIC and other groups organized the People’s Tribunal for Juvenile Justice at Seattle University, where they converted Seattle Councilmember Mike O’Brien to their cause. “Neither City nor County government is equipped to dismantle a criminal-justice system without the leadership of communities who live through it every day,” O’Brien reflected afterward on his blog. “EPIC presented data, stories, and facilitated discussion in a way that was healing and empowering. These community leaders are clearly part of the solution, not the problem.” He went on to sponsor a resolution, passed by the City Council, declaring that zero youth detention is a goal of the City of Seattle. The county has not passed a similar resolution.

Earlier this year, activists scored a tangential victory when they convinced the City Council to indefinitely delay construction of a new, unprecedentedly expensive police station in north Seattle. That seemed to suggest that the youth jail could also get derailed. But at the end of December, the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections issued a Master Use Permit (MUP) for the youth-jail project over activists’ objections—meaning that construction is imminent. “We’re expecting to break ground [this] year,” says Vaughn.

Despite the MUP, organizers are determined. “There’s a lot of momentum,” says Brown, “ … that’s escalating into direct action in a way that hopefully is getting folks to realize that it’s not an option to continue to dig your heels in and move the way you’re moving … People simply won’t stand for it. They’re not going to take it lying down.”

The hope, she says, is that continued pressure “shakes up folks who are gatekeeping” enough to convince them to redirect money to worthier causes. “The King County Council and Executive have an opportunity to be on the right side of history,” she says.

“We’re trying to have a paradigm shift in analysis of what the problem is,” says Brown. “It doesn’t happen overnight. But I just worked in city government for the last three years. When we want something to happen and we’re serious about it, it happens.”

cjaywork@seattleweekly.com

An earlier version of this story erroneously reported that the February 2015 King County Council protests were in the King County Administration building. They were in the King County Courthouse.