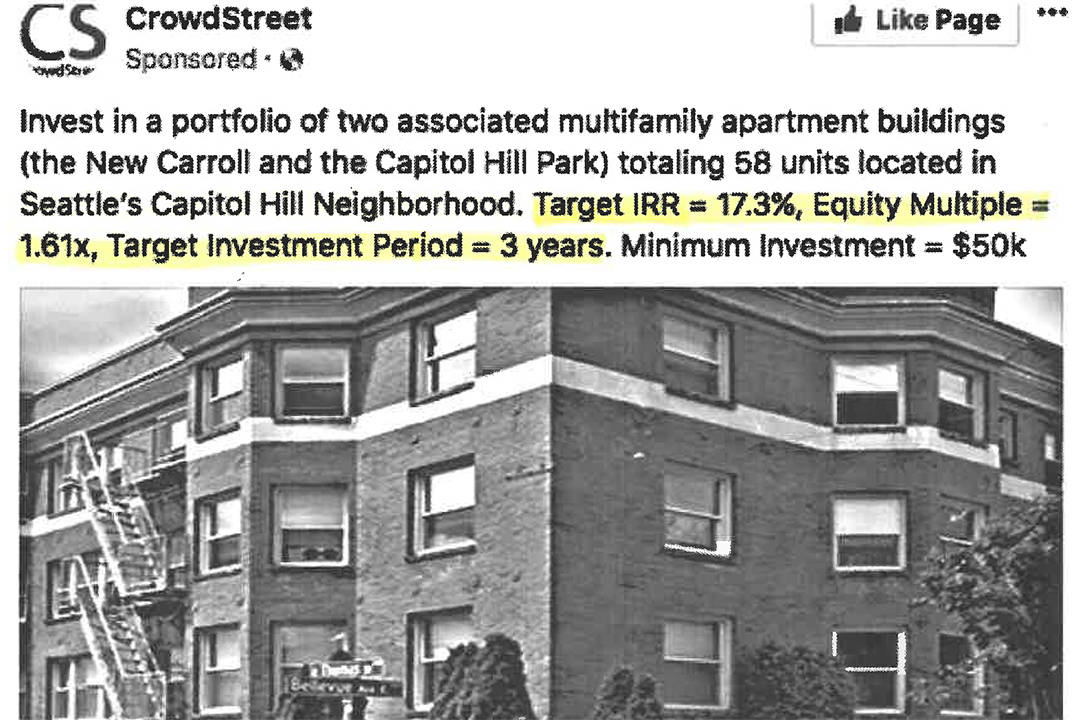

Before Seattle’s mayoral candidates were sparring over the role of speculative investment in Seattle’s housing crisis and whether to regulate the phenomenon, several Capitol Hill apartment buildings were purchased and bundled into an investment portfolio boasting an eye-popping rate of return of 17.3 percent.

In a note to potential investors, Mayfield Investment Company—the Portland, Oregon-based firm overseeing the portfolio—claims that since purchasing the two buildings, five apartments had “turned over” and “achieved” an average rent increase of 16 percent; the company notes it hardly had to do anything for the increased rents. “Only one had to be renovated,” the company writes.

Mayfield isn’t shy about letting their financial plans get out. In fact, they’re splashed all over Facebook, where Crowdstreet—the company advertising the portfolio to potential investors—urges users in Seattle to invest in the two properties and get a slice of Seattle’s rent-hiking bonanza. Those who live in the buildings, though, are less enthusiastic about the big promises being made with their rent.

Indeed, The New Carroll and Capitol Hill Park apartments are case studies on how much influence speculative investment plays in perpetuating Seattle’s inflamed housing market. And they raise questions about what role passive investors scrolling through Facebook should play in it.

The Capitol Hill Park and the New Carroll apartment buildings—adjacent to one another on the corner of Thomas street and Bellevue avenue, just across the street from Thomas Street Park—were purchased by the Mayfield in March 2017. The price tag was almost $23 million. The portfolio’s online listing indicates that Mayfield intends to hold the buildings while their value increases over time in Seattle’s white-hot housing market, for an eventual, profitable sale. The company hopes to raise $8 million from investors to cover unit renovations and projects. If all goes according to plan, they’ll hold onto the property for roughly 10 years before selling it.

Per John DesCamp, vice president at Mayfield, describes the firm as a “value-add company.” “We buy properties that have been run down or inadequately taken care of, fix ‘em up, make money out of it, and then sell,” he said.

He said that the immediate rent hikes are enacted to renovated units and units with concluding leases whose rates were set below what the market could bear by the previous property owner. “Any time you buy a building that has been substantially under-managed, the rents are typically not at market [rate],” said DesCamp. “The people who were running the building weren’t paying attention [to the market]. When there is a transaction like this, you typically want to bring your rents to market.”

In this case these hikes are estimated to increase rental revenue by 40 percent, according to an online ad for the portfolio.

DesCamp said that Mayfield isn’t as interested in turning a quick buck with rent increases than some other firms. He says that while some companies operate on business models that rely heavily on rents to pay investors, Mayfield is holding on to annual rent revenue for company profits, renovations—which he said will cost “several million dollars”—and debt repayment; the big investor payout comes from the eventual resale, though investors will also receive an annual dividend from rent revenue before the portfolio is flipped.

Things look less rosy on the ground for the inhabitants of the properties. After a Weekly employee was prompted on Facebook by Crowdstreet to achieve big returns on the two rentals, we went to speak with tenants at both the New Carroll and the Capitol Hill Park buildings to see how the deal sounded to them. Those we spoke with seemed largely unaware of the fact that their rented homes were part of a property deal getting advertised to their neighbors on Facebook, though they did say that their landlords have been busy conducting interior renovations.

“I had no idea about this. I hope my rents don’t go up,” said Owen Kroeger, 32, and a tenant in the Capitol Hill Park building since February of this year.

“I’m not sure how I feel about that. I mean if it’s going to raise rent prices artificially that’s not great,” said Daniel Grande, 29, who’s rented his apartment for two years. “A lot of the tenants in here have been there for a really long time. I know they’ve been doing a lot of refurbishments so I think everyone is kind of expecting that jump in rent prices but we don’t know what’s coming,” he added.

Grande said that most of the units in his building are one bedrooms, leased for around $1,500 per month ($1,650 for an added parking spot).

The big picture story behind Seattle’s sky-high rents is one of growth, a limited housing supply, and stark income inequality: The disparity between Seattle’s recent population boom due to tech industry job growth (and the high incomes attached to said jobs) and the numbers of housing units getting added to the market annually has resulted in continual rent increases.

However, mayoral candidate Cary Moon and others have argued that this narrative is too simplistic. She has argued that speculative investment and foreign buyers have artificially raised housing prices—due to increased investor interest—beyond the rates generated by supply and demand dynamics. Moon wants to explore whether the financializing of Seattle’s housing market is accelerating rent hikes due to landlords’ obligation to funnel returns to investors, as opposed to covering property operating costs and personal profit. “They are ruthless about keeping rents at the highest possible level, where mom-and-pop landlords might not be,” Moon told Seattle Weekly recently. “They might cut you some slack, because they like you, because you’ve been there 10 years, or because they know your mom. Real-estate investors don’t do that.”

Sherley Henderson, President of the Real Estate Investors Association of Washington, agrees with Moon, to an extent: she says that while rents do go up when investors motivate landlords to maximize rent profits, run-down properties get refurbished. “The end result [of investor driven rent hikes] does not help affordable housing. But it does substantially help living conditions,” Henderson said. “You don’t want tenants living in substandard housing.”

None of the tenants of the New Carroll or Capitol Hill Park apartments that Seattle Weekly spoke with complained of substandard living conditions in their buildings.

Moon’s opponent in the mayoral race, Jenny Durkan, at first slammed Moon’s anti-speculation proposal as xenophobic before tepidly endorsing exploring taxing speculative investment. Councilmember Lisa Herbold, got into a spat with the King County Assessor John Wilson over her request that his office help identify wealthy foreign home buyers to study the phenomenon; Wilson said that not only was he uncomfortable with tracking buyers by their nationality, but that the impetus for the request is a distraction from the primary issue driving Seattle’s sky-high rents: out-of-balance supply and demand.

Henderson alluded to values driving investor behavior as well. “I know that the investing in Seattle is very, very active,” Henderson said. “I think the values are pushing investors toward [value-add projects].” She added that Mayfield’s portfolio is quite small compared to typical real estate portfolios in Washington state, which usually include upwards of 30 bundled properties (in addition to asking for higher minimum contributions from investors; this may explain why the invitation to invest in the Capitol Hill projects was even offered to newspaper editor).

Whatever the case, the brutal nature of Seattle’s turbulent housing market is increasingly normal for tenants. One tenant of the Capitol Hill Park, who declined to give his name, said that he wasn’t surprised to find out that his home was part of an investment portfolio. “That’s what every building is like down here. There’s no more mom-and-pop apartments. That’s just how it is.”

news@seattleweekly.com

This post has been updated to correct the name of the park the apartment buildings are near.