On a Saturday afternoon at Vashon Presbyterian Church, an instructor reads a prompt to six parents: “Your 13-year-old texts you, asking for birth control.”

The role-playing begins. A dad runs his hands through his hair. A mother fidgets in place while another audibly tells the group, “This is hard.” Each tries to remember what they were taught moments ago: Be open, don’t jump to conclusions, and try to relate.

The exercise is part of a pilot program called LiFT (Linking Families and Teens). The program hopes to ease conversations about sex between adolescents and adults with the ultimate goal of reducing teen pregnancy.

For the past three years, Planned Parenthood of the Great Northwest and the Hawaiian Islands implemented and studied this program’s effect in rural areas where access to sex education resources is limited. In this case, it’s the isolated community of Vashon Island. “Even though we live between Seattle and Tacoma, it’s a rural area and it’s really hard for teens to access resources,” says 17-year-old Ray Lewis, a participant in Saturday’s class. “The ferry boat, taking the bus, and getting to Planned Parenthood—that’s a lot of stuff. So it’s important that [Planned Parenthood] comes to us.”

But the future of the program—along with 80 other sex-education programs across the country—is uncertain because the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is taking steps to end funding for Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPP) grants.

The TPP began in 2010, and is now in the middle of its second round of funding. Some grants help organizations distribute sex-education programs while others, like the one given for LiFT, fund research to study a program’s effectiveness.

Since TPP’s inception, data provided by the Centers for Disease Control show the number of teens having sex decreased by roughly 10 percent. The teen birth rate fell at an even higher rate—down 41 percent since 2010, according to a CDC study. LiFT has already seen positive outcomes. According to Planned Parenthood data analyzed by a third party, those who took the program were more likely to use condoms and reliable birth control.

Despite promising results, all 74 organizations receiving 81 TPP grants were notified last July that HHS would terminate their funding on June 30, 2018—a full two years before the grant was set to run out. “It’s so tragic,” says Carole Miller, chief learning officer for Planned Parenthood of the Great Northwest. “We are three years into five-year projects, and we are seeing really positive early outcomes.”

In February, 10 organizations filed four separate lawsuits against HHS claiming the department unlawfully terminated their grants. Western Washington was at the center of this legal battle, having received the largest number of grants of any region in the country. King County and Planned Parenthood of the Great Northwest (who received four grants in 2015) are named plaintiffs in two separate suits. Since filing in February, judges in three of the four suits have ruled in favor of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program grantees, agreeing that the termination of the grants by HHS was illegal. “It doesn’t guarantee funding for anyone, but it is a strong basis to continue the grants,” explaines Sean Sherman, attorney for Public Citizen, the nonprofit advocacy organization suing HHS on behalf of the grantees. HHS still has other options to end funding, including terminating each grant, but to do so they would have to show cause.

The fate of funding is especially uncertain for the other 62 programs not named in the initial four lawsuits. To prevent them from losing funding on June 30, attorneys at Public Citizen filed a class action suit last Friday, to put every grantee in the same position as the others that have already won. King County is not named in the class action suit because its fate is yet to be determined. Filed by Democracy Forward on the same day as the other suits, the county’s case is the only one yet to go before a judge. King County’s next court date isn’t until the end of May. “[We’re] focused on getting the funding restored so we can finish our work,” says Heather Maisen of the Seattle King County Family Planning program.

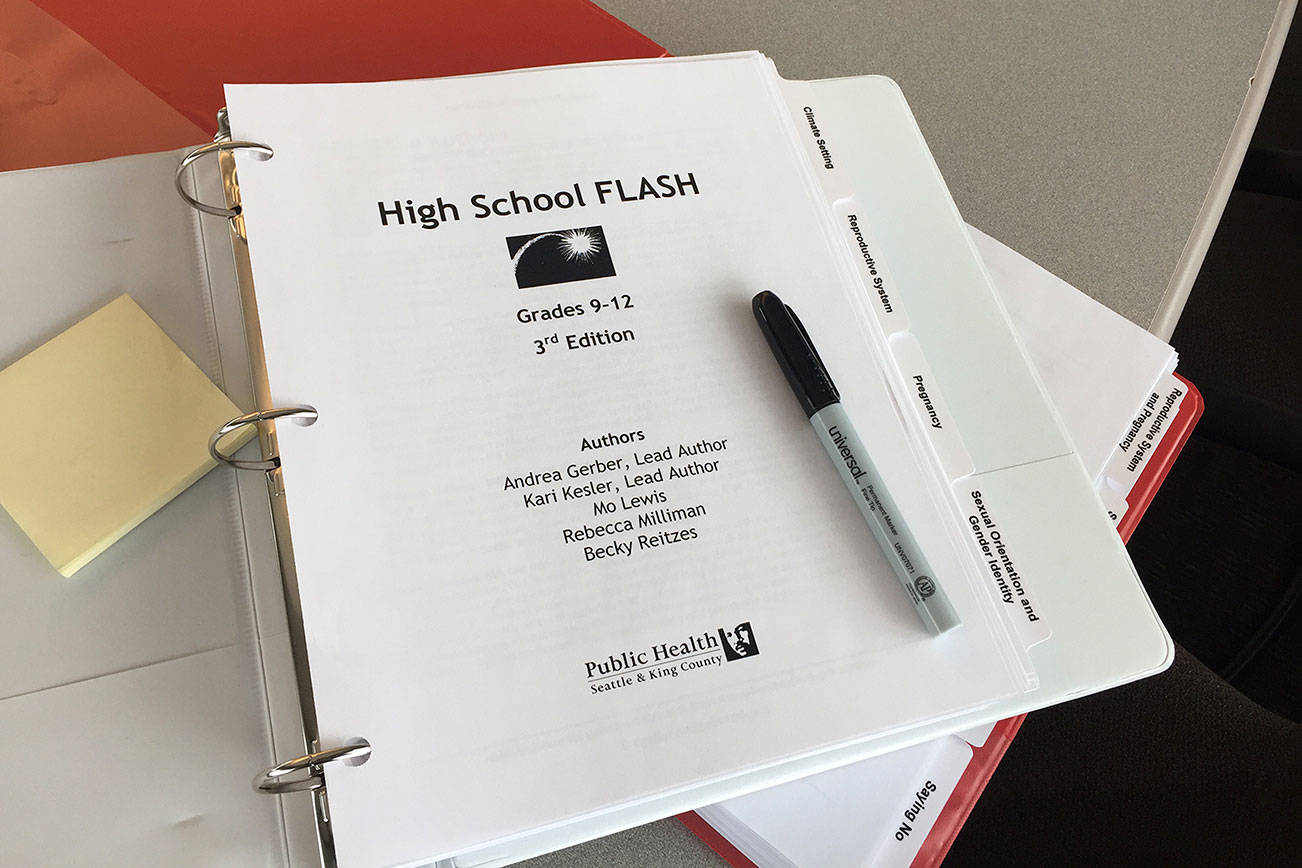

King County was awarded a $5 million TPP grant in 2015 to study the effectiveness of its FLASH program. Developed in the 1980s by Seattle and King County public-health educators, the science-based program has been used (with updates) by all school districts in King County, other districts in Washington, and select schools in 44 other states. To date, however, the effectiveness of the widely used program has not been studied. The TPP grant allowed King County to do that, implementing the program in 20 schools in Minnesota and Georgia. “We’ve never been able to study it because it’s such an undertaking and we need a large amount of funding to do so,” says Maisen. “So this was a unique opportunity for us.”

The study is currently going into its fourth year, but it’s unclear if things will come to a halt if funding runs out on June 30. “You spend $3 million on it, but now you’re going to take the money away and not get the answers. It’s just amazing that you would want to do that,” says Keith Seinfeld, spokesperson for Seattle and King County Public Health. “That’s the big head-shaker in all of this.”

HHS has yet to give a reason why it suddenly decided to cut funding for TPP program grantees, but the department has given hints. In August the department published a news release titled “False Claims vs. The Facts” claiming “73 percent [of TPP grantees] either had no impact or had a negative impact on teen behavior.” The release adds that the program “cannot be the reason for the drop in teen birth rates” and “is a waste of taxpayer money.” HHS did not respond to Seattle Weekly’s repeated requests for comment on the issue.

Planned Parenthood’s Miller wholeheartedly believes the funding cuts are ideological. “I am quite sure this is politically motivated,” says Miller, “and it is not based on what’s best for kids.”

Since 2015, funding has increased by $45 million for sex-education programs that promote abstinence-only or “sexual-risk avoidance” curriculums. The federal funding comes from two sources: Sexual Risk Avoidance Education grants and Title V funding. In total, $100 million in federal dollars will go toward abstinence programs in 2018, the highest level since 2009.

That number may more than double if HHS succeeds in shifting the roughly $110 million Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program dollars to new grantees, which appears to be their goal. On April 23, HHS released a new grant notice calling for programs that “provide cessation support” and tell teens to “avoid sexual activity.”

In 2020, the current TPP grants will run out regardless of any legal victories. But Public Citizen’s Sherman is sure the current fight is worth it. “We’re talking about two more years, but we’re talking about the needs to complete those programs. The data and information that we’ll learn, that is what’s really important,” says Sherman.

Miller contends it’s bigger than that. Defunding these research grants would be a step backward. “It’s a huge deal. It’s the first time the field of sex education has had the focused attention on studying programs and really finding out what worked for this generation,” says Miller, “and it’s being cut short.”

Update (May 2): The story originally stated that the FLASH program was used in four other states, while the actual number is 44.