When voters say “yes” or “no” this fall to Proposition 1, they in essence will be saying “yes” or “no” to light rail.

Elsewhere in this package you have read arguments for and against ST3, and nearly every one of those arguments will come down to whether or not the light rail system now in its infancy in Seattle should be expanded region-wide, from Tacoma to Everett, from Redmond to West Seattle.

Central to arguments both for and against will be the region’s history so far with light rail, with proponents arguing that it has fundamentally changed the way people get around Seattle — and that that shift is necessary for the entire region — and opponents saying it has been too slow in coming on line, too expensive to build, and not as impactful as others make it out to be.

Voters first said yes to light rail back in 1996, with the $3.9 billion Sound Move initiative, which also created Sound Transit as a regional authority. Like ST3, the package offered a mix of light rail, bus and commuter rail services. But the big-ticket item was a $1.7 billion light rail system running from the University of Washington to SeaTac Airport, expected to be completed within 10 years. Creating an entirely new transportation system in Seattle promised both big risks and rewards. It delivered both.

Early on in the construction of Link Light Rail, it appeared Sound Transit may collapse completely, and the light rail plan along with it. The cost of the project quickly began to balloon — the Associated Press reported in 2001 that the project was already $1 billion over budget, and no rail had even been laid down. The cost overruns led federal officials to withhold large grants, further imperiling the plan’s finances. A series of executives resigned from the agency, and in 2001 new CEO Joni Earl announced that the light rail line would only go 2/3s of the promised length — stopping at Westlake rather than UW; would cost more; and would take longer to complete. Not a good way to introduce taxpayers to a new, multibillion-dollar agency.

And yet, with all that, voters within the designated Sound Transit taxing district continued to respond to the idea of a light rail system in the region. In 2008, before the initial expanse of light rail had even been completed, voters approved ST2, which included 36 miles of new light rail track.

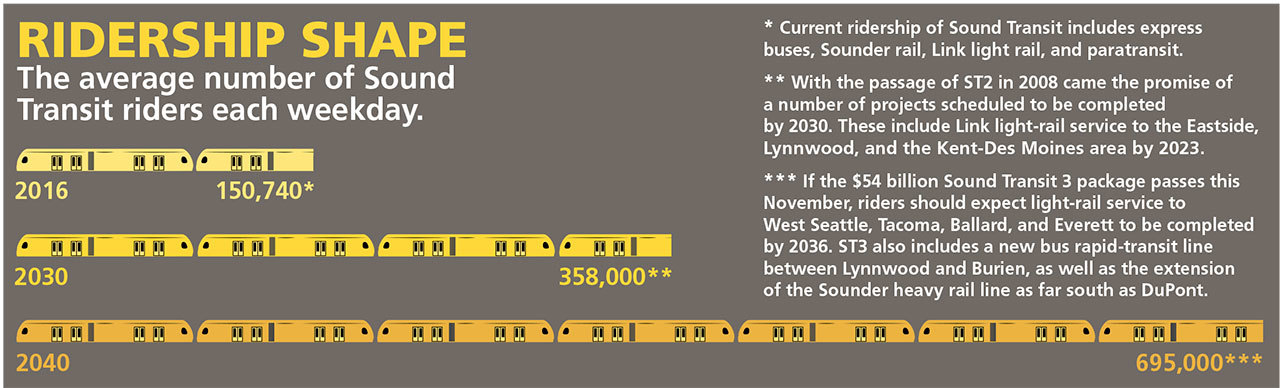

That vote marked the beginning of brighter days for Sound Transit, and in particular its light rail system. In 2009, the light rail from Westlake to SeaTac finally opened; also, in the mid-aughts, the federal government restored the hundreds of millions of dollars in funding it had previously withheld, allowing Sound Transit to move forward with its plan to bring light rail to Capitol Hill and UW under the auspices of the 1996 Sound Move measure. While critics long groused that light rail ridership has not lived up to what was promised, with the UW-SeaTac line finally complete, ridership has exploded — up 77 percent in summer 2016 compared to summer 2015 — and is far exceeding forecasts.

It’s not hard to understand why the public has responded to the new line. People have attested to literally crying as they commuted from the U District to downtown in eight minutes after years of seeing trips to the city center become more and more impossible due to surface street-traffic snarls. Light rail advocates hope that Everett, Eastside, and Tacoma commuters will imagine the same joyous escape from the freeway in their own lives and approve a plan that would connect them to the system (though, to be clear, trips from out of Seattle promise to be longer than eight minutes; the Tacoma Dome-to-downtown Seattle trip is pegged at 70 minutes).

There’s also evidence that Sound Transit is becoming better at predicting how expensive light rail will be to build, and how long it will take to build it. Mike Lindblom at The Seattle Times recently calculated the total cost overruns of the 1996 ballot measure, and arrived at about 86 percent. Not good. However, in applying for federal grants to finish the Westlake to UW line, the agency was required to complete a new budget and timeline; it beat both.

And yet the early history of light rail will provide critics with a ready — and legitimate — argument against the system: its ability to lock the region into wildly expensive transit systems. Once you start laying track, it’s very difficult to scrap the plan altogether.

Still, if you’re one of those people crying on your commute to downtown, you probably don’t care.