Bill Boyce and Brenda Fincher had similar experiences when they moved to Kent in the 1980s.

By then, the South King County city was decades removed from its agricultural heyday, when it was billed as the “Lettuce Capital of the World” for the verdant bounty that sprung from the area’s rich Green River valley soil. Boyce and Fincher were settling down in a city that had long since shifted to manufacturing, including a Boeing plant that built the Apollo Moon Buggie on top of land that was once just good for salad greens.

Still, Kent in the ’80s retained some of the marks of a sleepy Washington farm town: light traffic, good schools, and a nearly all-white populace. “In 1984, you could drive a long way and not see another minority,” says Boyce, who is black and grew up in North Carolina.

Fincher, also African-American, recalls: “Early on, when I would go to my kids’ classroom, there wouldn’t ever be any question about which ones were mine… . When I went to watch Little League, everyone knew who I was associated with.”

Boyce and Fincher, both members of the Kent City Council, don’t look back on their early days in the city in any kind of negative way. They both chose to settle in Kent. Boyce joined the Army at 18 and was stationed at Fort Lewis. When he got out he wanted to stay in the area, and thought Kent fit the rural Carolina lifestyle he was accustomed to better than the hustle and bustle of Seattle. He and his wife raised five children in the city, all of whom now have college degrees. Fincher also has a military background—both her father and ex-husband were in the Army. When her husband was discharged (he was stationed in Tucson), they settled in Kent because it seemed like a good place to get established.

Still, their early memories of Kent draw a striking contrast to the city they help govern now. Starting in earnest in the 2000s, Kent has undergone a rapid transformation that has made it what it is today: the second largest majority-minority city in the state. According to the 2010 census, 49 percent of its 125,000 residents are non-Hispanic white. In the 2000 census, the city clocked in at 70 percent white; in 1990, it was 90 percent white. The demographic shift has not been due entirely to a growing black population. Nearly 5,000 refugees have been resettled in Kent since 2003, with Iraq the largest source. Sizable Asian, Pacific Islander, and Latino populations also call the city home. It’s common knowledge around town that some 130 different languages are spoken in the Kent School District, a fact cited with a mixture of pride and astonishment.

Though not the sole reason for Kent’s diversification, the number of African-Americans residing in the city has grown exponentially. Between 2000 and 2010, the black population in Kent grew 98 percent. School data shows that, in just the past six years since the census, the black student body at Kent Meridian High School in the heart of Kent has grown by 14 percent.

There’s little question why. “People of color are getting displaced to Kent,” Fincher says.

“Prices are going up in Seattle. People are being somewhat forced from their community for one reason or another,” Boyce says.

Kent, in other words, is on the receiving end of Seattle’s gentrification. It’s been a fact for decades that the Central District, which at one point was 80 percent African-American, is losing its distinction as Seattle’s black neighborhood. The reason the CD was so heavily African-American to begin with were the racist real-estate rules that kept black people out of other Seattle neighborhoods. Still, the tightknit community that formed came to be cherished. It was a place African-Americans could form their own culture in a notably white city, a place they could get their hair cut and find good soul food. But today the Central District is feeling less diverse than ever, as up-zoned condos and chic, tech-oriented restaurants replace family homes and legacy businesses. Widely cited figures generated by the Nielsen Company put its black population at 20 percent and shrinking. With the transformation has come a question: Where will black Seattle regather when the CD is completely lost?

Some people have suggested Kent.

You needn’t look far to find evidence that this might be the case. Along with the demographics, some Central District institutions have made the move south to Kent. There’s an Ezell’s Famous Chicken there now. The Rev. Leslie David Braxton left Mount Zion Baptist Church to establish his own church in Kent, New Beginnings Christian Fellowship. That was 15 years ago, and he was then ahead of the curve; now he’s right in the middle of it and his congregation is thriving. “Many of the people who used to live in the Central District have moved to the south towns or the edge of the city where they can get more house more affordably,” Braxton told The Seattle Times in 2014. “It’s simple economics.”

And yet for all this movement—the people, the businesses, the churches—those who live there are skeptical that the city will ever grow into anything like a “new” Central District. The reasons given are many: Kent’s suburban feel; a dearth of black-owned businesses; the simple fact that the racist housing laws that helped create the CD in the first place don’t exist anymore.

But while Boyce says he likes visiting Seattle and the CD, he is unfazed by the changing face of African-American King County. “We don’t have to all be in one area, and I don’t see that being a concern, an issue,” says Boyce, who works in Human Resources at Boeing and serves as the president of the Kent City Council. “I don’t see Kent being the new CD. I wouldn’t put that label on it. We’re too spread out. I don’t have any blacks in my cul-de-sac.”

He notes that black residents in Kent have more buying power than they did in Seattle, and that the school district is strong. Those are both positive developments for people, he says. “I used to go up to the Central District to get my hair cut,” he says. “At the barbershop they’d be saying, ‘Don’t sell your home, don’t sell your home.’ But that dollar looks good. Time don’t stand still.”

Others aren’t so sanguine. Vivian Phillips, chair of the Seattle Arts Commission—who unknowingly sparked my curiosity about Kent with a comment in The Seattle Times this summer about the city being considered by some the new CD—confirmed to me that she’s heard Kent being talked about as a new center of black culture in King County. But she entirely disagrees with the sentiment, for the simple reason that what’s being lost cannot simply be replaced by demographics alone.

“I totally understand it strictly from a population perspective. But it doesn’t resonate with me from a cultural perspective,” she says by e-mail. “And by that I mean that I and others don’t have memories of our favorite barbecue place, or hair salon, or soul-food restaurant, or gathering place in Kent. All of that points back to the Central Area. So there may be more African-Americans in Kent today, but the African-American soul memory resides in the Central Area.”

Gwen Allen-Carston poses for a portrait on December 8, 2016 in her African-American beauty supply store, C&G Hair and Beauty Supply in Kent, Washington. Allen-Carston is the executive director of the Kent Black Action Commission. Photo by Jovelle Tamayo

Gwen Allen-Carston is the executive director of the Kent Black Action Commission, a group she helped form in 2011, and she too feels the lack of a black community among a large black population in Kent. She admits part of her motivation for forming the commission could rub some the wrong way, but uses it as proof that she doesn’t sugarcoat her views on things. A small business owner, she says she was attending a business development meeting with the city when an Iraqi refugee began discussing various government programs that were helping him and his family get on their feet. She was immediately struck by the fact that no such services were offered to African-Americans. “I’m still waiting for America to give me my 40 acres and a mule,” Allen-Carston says. “When I look at an African-American person who immigrates from Seattle, it’s like a foreign land to them. And nothing is set up for you. You wonder, ‘What the hell is going on?’ ”

Driving around Kent’s sprawling East Hill, Allen-Carston has an almost encyclopedic knowledge of who owns what businesses. “That’s owned by a gentleman from Pakistan,” she says, pointing to one. “If you want good Punjabi food, that’s the place,” she says of another. “People are feeling like this group of guys—”, she says, pointing at a department store but referring to its owners, “—they are just buying everything. When you look inside, they’re serving the needs of their people. They even got a pet shop up in there.”

It’s hard, she says, to not feel as if a hierarchy is in place in Kent. “White people first. Immigrants second. Then black people maybe on the list somewhere,” she says. “I don’t want to get lost in the shuffle.”

Immigration is a clear and present fact of life in Kent, with ample support shown for immigrant communities. Boyce notes that following the election of Donald Trump, the city convened a listening session for members of the community to express their concerns for a possible crackdown that could adjoin the incoming administration. Kent’s State Sen. Karen Keiser, who is white, was invited to Washington, D.C., in 2013 by the Obama administration to help lobby for comprehensive immigration reform. “In inviting the brightest minds in the world to study in the United States and to open businesses here, we grow our economy and ensure that the United States continues to be a home for innovation and a place where ideas become successful realities,” Keiser said when stumping for Obama’s plan.

However, for all the support shown, an undercurrent of angst surrounds the issue as well. Listening to Allen-Carston, it’s hard not to hear echoes of angry white voters who rallied around Trump on the grounds that they were getting left behind by American immigration policy. Allen-Carston and I met on the Monday before Election Day at a Fred Meyer Starbucks. As I waited for her to arrive, I watched a Russian-speaking woman coo over a baby held by a black woman in a Muslim headscarf. Then a white man named Doug began talking to me. When he learned I was a reporter, he quickly turned to the topic of immigration and an unsettling anger crept into his voice. “If Donald Trump doesn’t win there’s going to be a revolution, because Hillary’s going to give this country away!” he growled, waving his hand to take in the bustling, multicultural shopping center around us. Then he stormed off.

When I told Allen-Carston about Doug, she insisted there was a big difference between she and him. Namely, she has little doubt that he’d lump an African-American like her in with all the rest of the nonwhite residents of Kent.

“What I would say to Doug is you need to rid yourself of that feeling and get to know reality. The browning of Kent is happening, but if you’re going to be stuck-on-stupid, you’ll never accept that,” she said. At another point she told me of her beliefs: “This is not against any other culture.”

What Allen-Carston wants more than anything else is support from the city of Kent for black small-business owners. She says more African-American-owned businesses would not only economically empower the community, but help create a community itself, by giving African-Americans places to gather—similar to what was (and to a certain extent still is) the case in the Central District. “Everybody and their mama knew, where the black people at? They’re up in the CD. We can’t say that in Kent,” she says. “We’re spread all over.”

Allen-Carston’s small store in a strip mall on East Hill testifies to the lack of businesses and services geared toward African-Americans in Kent. While it’s primarily a hair- and beauty-supply store—extensions, skin cream, and the like—she has also started selling Louisiana hot sauce and cans of black-eyed peas. A bookshelf is laden with works by black authors; another counter serves as a clearinghouse for fliers about African-American events in the area. Explaining the odd mix, she says, “I want people to feel like they don’t need to go to Seattle for their basic needs.”

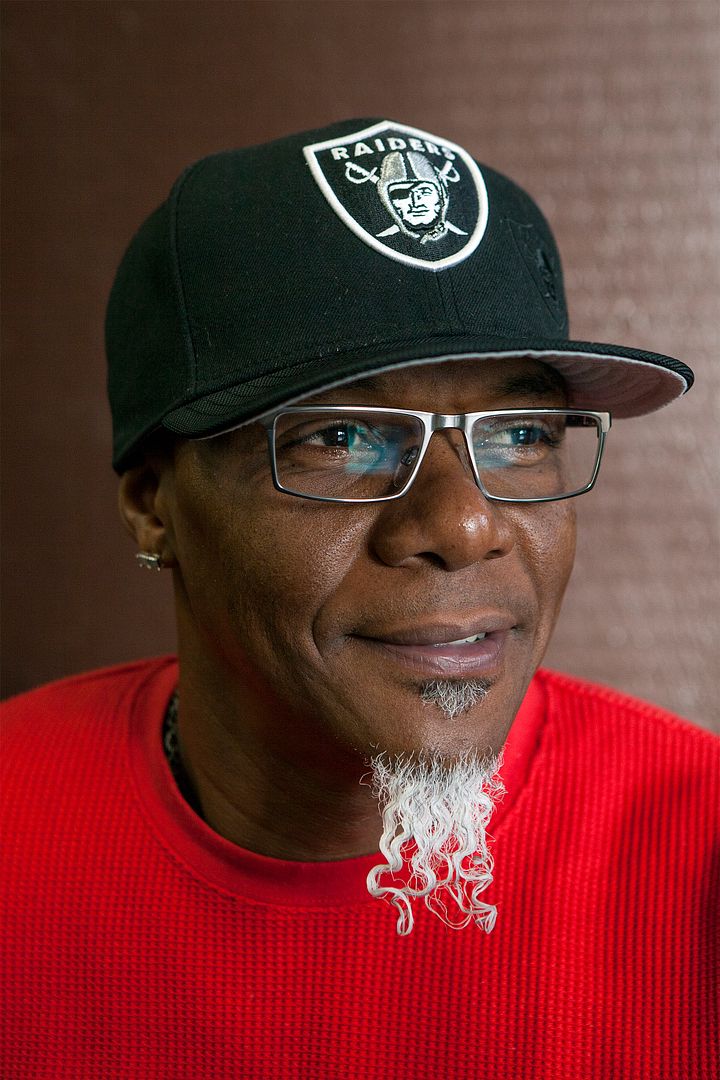

City Council President Bill Boyce poses for a portrait on December 10, 2016 outside Kent City Hall in Kent, Washington. Photo by Jovelle Tamayo

The “browning” of Seattle suburbs like Kent is not a new phenomenon, nor is it unique to King County. In Harper’s recently, Rebecca Solnit noted similar phenomena in San Francisco and New York City, writing, perceptively: “Before the current millennium, urban centers had become leftovers, as well as containment systems for non-white people, kept out of the suburbs by covenants and redlining and hostility. Now affluence and whiteness are retaking the city, slowly but surely turning it back into an exclusionary zone.” Solnit writes this process would be “shocking … if it weren’t so slow, subtle, and complex.”

In general, Solnit argues, this is a problematic development, since suburbs were never designed for poor people. Public transportation is typically worse than in the cities; jobs are farther away; police forces tend to have less funding and less training. The police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., outside St. Louis brought renewed scrutiny to small suburban police forces serving and protecting poor, diverse populations without the resources to either serve or protect. “It’s no accident,” one expert told USA Today in 2015, “that the [law-enforcement] problems that emerged last summer came from a small police department like Ferguson.”

Kent is about six times the size of Ferguson, and is wealthier, but it’s not a stretch to see similarities. Ferguson, too, used to be nearly all white; now it’s majority-minority. Both are independent municipalities with complex populations living in the shadow of a big city, out of sight and out of mind. Also like Ferguson, Kent’s police force does not reflect the diversity of the city it serves. In recent years the force has been actively recruiting nonwhite officers, but still has a force that’s 83 percent white (down from 87 percent in 2011).

Whatever the parallels, Council President Boyce twice brought up the Kent Police Department’s response following the Ferguson shooting in our conversation about race in his city. “After Ferguson, our police chief took a proactive stance. He’d go to different sectors and learn about any concern with policing. As a city we try to address it. We are one big city, we’re a diverse community, and we have to embrace that,” he said. And later: “Our police, they went out and started talking to people. They were trying to get out in front of it. If you don’t have a good relationship between people and the police, you’re in a world of trouble.”

Assistant Police Chief Eric Hemmen tells Seattle Weekly the outreach efforts did not begin with Ferguson, but says it did “re-emphasize that what we were doing is needed.” Hemmen says by e-mail that the department has continued to hold public meetings, and this year “conducted a community project in which we interviewed 13 different focus groups to determine the public’s expectations, opinions, perceptions, and attitudes of the Kent Police Department … We are currently in the process of taking the main themes from the community meeting and the community project and setting up a plan of action on how we can continually improve our relationships with our community.”

When I ask Boyce if racism existed in Kent he responds: “To the best of my knowledge, I’d say no. I think Kent is a very warm and embracing place. You always have pockets of things.”

Asked a similar question, Fincher notes that all the change can be hard for some longtime, white residents, but doesn’t spill into any kind of hostility. “You have people who lived here when it was the Lettuce Capital of the World. Now they have to deal with cultures that aren’t theirs, food that isn’t theirs. It’s a big change. But it’s been refreshing for me.”

The diversity, the food: What Fincher is enjoying are the very things some fear Seattle could lose under the sweep of gentrification. As Solnit put it in her essay: “The North American and European cities that are becoming elite strongholds are pushing out diversity, complexity, cultural production, and dissent. They are becoming what is worst about the suburbs.”

Which is to say the suburbs are becoming what is best about the cities. Fincher, like everyone else, is doubtful that Kent will ever really replace what the CD was, no matter how many black people move to the city. She understands there is loss in that. An employee at Holy Spirit Catholic Parish in Kent, she says Immaculate Conception parish in the Central District has long been a bastion of black Catholicism in the area, an element of the church otherwise underrepresented in the region. Were that congregation to go away, the impact would be felt by black Catholics across King County, not just those in the Central District. But she also frames Kent as an opportunity to forge a new model, a city that lives up to the ideals of multiculturalism, since it has no choice.

“The CD is a tightknit community … the grocery store, the barber shop, the beauty shop, also the restaurants. Kent doesn’t have that. There is no good soul food out here, and I don’t see all those businesses cropping up in Kent,” she says. “Here we’re going to have diverse neighborhoods, and I hope people get together and play together … You don’t have those solid black areas, Latino areas, Sikh areas.”

Joe Lee, a barber and the owner of Distinct Image Barber Shop in downtown Kent, Washington, poses for a portrait on December 10, 2016. Lee, who left Seattle’s Central District in the late 1980s, opened his barbershop business in Kent more than 16 years ago. Photo by Jovelle Tamayo

To date, Kent has appeared somewhat insulated from the economic factors bearing down on the Seattle Metro area. Zillow reports the median home price is $335,900, far lower than that of the greater Seattle metro area. The average rental cost is $500 per month cheaper than the metro average. The housing market, as Zillow puts it, is “cool,” whereas the metro area overall is “very hot.”

Still, there is some concern that Kent too could see its lower-income residents pushed out by housing costs. Allen-Carston says tech money has been showing up in town, and is quick to point out a Microsoft Connector stop when we pass it on East Hill. Housing prices are up 12.3 percent from last year.

The Kent City Council has recently begun looking into Section 8 housing discrimination, in which landlords refuse to rent to people who are receiving federal housing assistance. The issue extends beyond any single racial demographic. But if discrimination of that kind is practiced on a large scale, it’s feared, people pushed into Kent because of prices in Seattle could soon be pushed out of Kent in turn. As such, Kent is considering whether it should follow Seattle’s lead in banning Section 8 housing discrimination. Otherwise, Fincher fears, Kent will soon be losing the diversity she’s enjoyed seeing rise around her in the past three decades.

“As the rents rise here, the incomes don’t increase,” she says. “That’s driving people further and further south. They’re moving to Graham because of housing costs here.”

dperson@seattleweekly.com