The word is out about housing prices in Seattle.

I was on vacation two states away recently, making small talk with an older couple. When I mentioned I lived in the Seattle area, they looked aghast. “Our daughter and her husband live in Seattle. He’s a doctor and she’s a lawyer, and they can’t afford to buy a house,” the father said. “It’s terrible.”

Tell us about it. Seattle housing prices have, arguably, overtaken traffic as the go-to thing to complain about at parties. Plenty of statistics back up those cocktail anecdotes. The real-estate metrics firm Estately last week released a study showing that 40 percent of all single-family homes put on the market in Seattle in February were listed at more than $1 million. The average monthly cost for a one-bedroom apartment in Seattle has gone from $925 in 2011 to $1,978, according to the rental database Rent Jungle. Little wonder that a recent survey conducted by regional land conservancy nonprofit Forterra found that 45 percent of millennials believe they will eventually have to move out of the city because of housing prices.

The Forterra study shows that rising housing costs are a regional issue not confined to Seattle (millennials in Snohomish County are even more concerned with it than those in Seattle). That said, there’s no doubt that this city’s cost of living has many people looking just outside the city limits for their next house or apartment.

What follows are five stories about young people who have found refuge from Seattle prices in the ‘burbs, and the joys and challenges that have followed. We don’t seek to sugarcoat the issue: Moving out of Seattle can mean more chain restaurants and fewer indie shops, longer commutes and fewer nights out on the town. But it’s also a reality that many people have faced, and many more are facing. And it’s not without benefits. As one of our subjects put it: “Having all of our own space without shitty downstairs bro neighbors is amazing.” DANIEL PERSON

When I ask Holly and Amy Seiberlich, a pair of happy and hardworking newlyweds with two dogs and a two-bedroom house in Bothell, if there is anything about Bothell that people in Seattle might not know—anything surprising, say?—they rack their brains for a moment. And then another moment. “Mmm, no, not really,” says Amy, laughing. “It’s just another suburb.” Although, she adds, “It’s cuter than your average suburb.”

There are a few nice things, of course, like the new PCC Natural Markets that opened a mile from their house. Amy announces this development with genuine gratitude—it’s easily “the best thing that happened to us” in the year-and-change since they moved—while Holly jokes that this “perfectly sums up life in the ’burbs: When there’s a new grocery store, that’s, like, the big hit!” There’s also Preservation Kitchen, which offers seasonal fare and microbrews inside the stately brick home of a former Bothell mayor, and the McMenamins Anderson School, which has, among other things, a wood-paneled cabin where you can drink whiskey and play cribbage and occasional live events, such as a ’90s music-video dance party. “I’d say it’s got more of an adult focus than the rest of Bothell,” Amy says of McMenamins, although, like most spots in Bothell, it’s very kid-friendly. Downtown Bothell is composed of a charming little main street about three blocks long (“If you fall asleep on your bus, you will miss it,” explains Holly), but at least, unlike some suburbs farther north, it has a charming little main street. The best thing about Bothell is probably its public library. And the closest, hip-ish hangouts the couple can think of—a string of bike- and dog-friendly brew-pubs along the Burke-Gilman Trail—are technically in Kenmore.

But at least it’s close to regional gems—Burke-Gilman, Lake Washington, the bucolic wineries and distilleries of Woodinville—and there’s a direct bus to downtown Seattle. It’s also under construction. Main Street is getting renovated, green spaces are getting spruced up. “Bothell’s fun, but you know … it’s developing its culture,” Amy says, sweetly. “It’s a lot of family culture. And we’re two gay ladies.” Sure, they’re married and have dogs, but they don’t have kids yet, so it’s easy to feel isolated; they jokingly lament the chain stores, the soccer moms, and the general dearth of cool stuff. Their current, closest amenities: an Applebee’s around the corner, which is next to a Wendy’s, across from a Taco Bell.

“Now that we’ve lived in the ’burbs for about a year and half, I fantasize about living in town, or closer, again,” Amy says.

In the meantime, they each commute—Amy to Kenmore and Wallingford for grad school at Bastyr University, Holly to Harborview, where she works nights as a registered nurse. The 522 gets Holly most of the way to Harborview, but combined with getting to the park-and-ride, that takes an hour, plus another 10 or 20 minutes to either bus or walk that last mile. It’s long, but she’s resigned; for now, it’s just three days a week.

Before Bothell, they were a bit closer in, in a teensy townhouse near 90th and Aurora. The house had its pros—an eclectic mix of neighbors, non-chain restaurants within walking distance, and the E line, which got them downtown in 20 minutes—and they considered buying. But it also had its cons: three break-ins to Amy’s car and multiple shootings within a block of their house, all within six months. Plus it was about the same price as they’re paying now, for barely half the space and no yard. In Bothell, they’ve got a quarter-acre and three apple trees—an embarrassment of riches.

Also, Bothell is a good investment—its home values shot up 11.4 percent in the past year alone—but for the Seiberlichs, it’s not forever. “It feels OK, for now,” says Holly. “But it feels like it would be really easy to just stop paying attention and stop thinking and all of a sudden you’ve been living in a cultureless vanilla community for like a decade. And I don’t want that … ’cause I grew up in the suburbs. I don’t want that.”

Their hope is to, someday, move to a more affordable place entirely—maybe back to Alaska, where Amy is from. “It’s where we are right now,” Amy says. “There’s nothing wrong with it or anything. It just doesn’t feel permanent to us.” SARA BERNARD

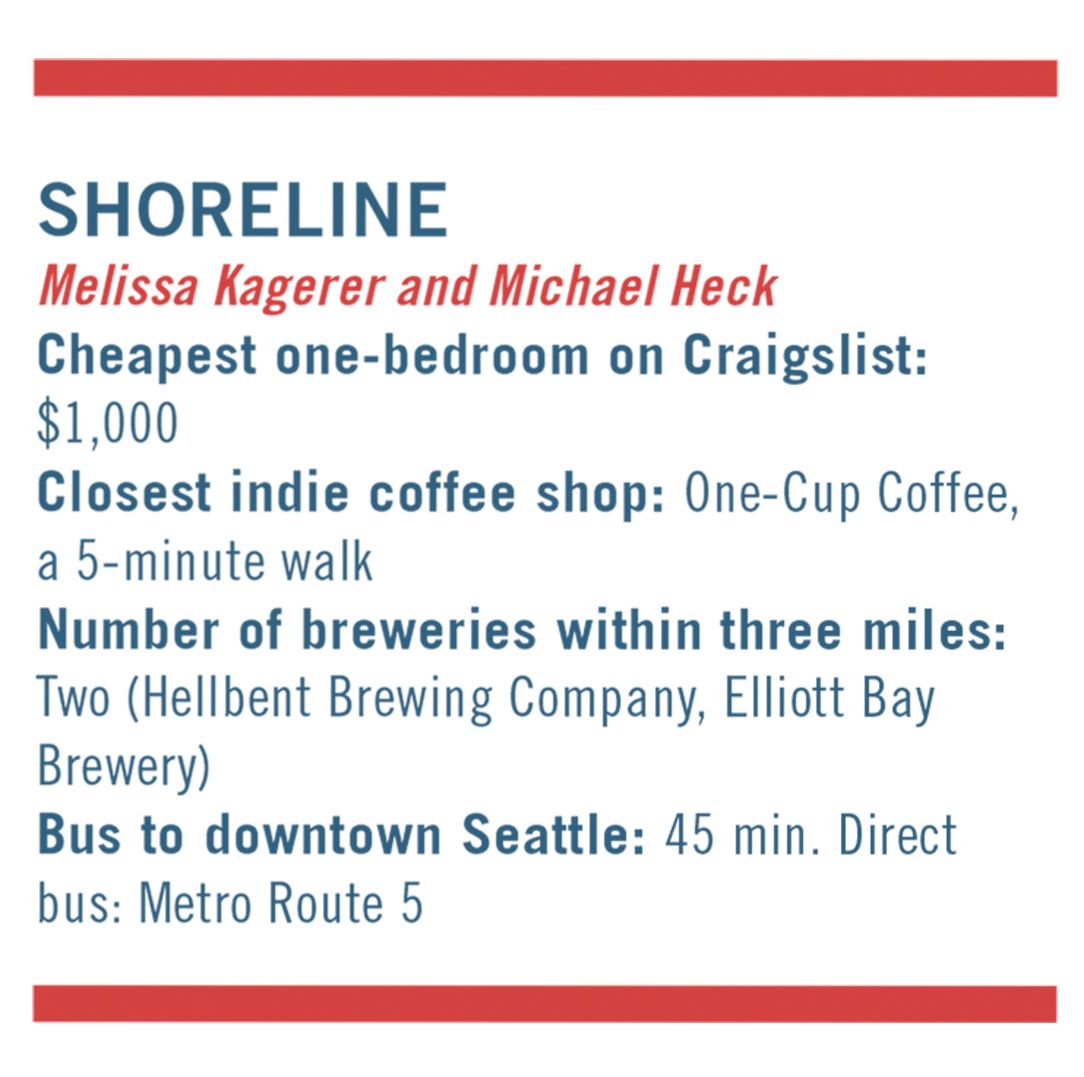

Surprises can be fun when your friends plan them, but when it’s your landlord, not so much. Partners Melissa Kagerer and Michael Heck had lived in their sizable $1,450 north Seattle two-bedroom for two years along with a friend, an arrangement that suited them perfectly. The location was premium for their needs: Heck worked as a graphic designer at the Fantagraphics Books office in Lake City, and Kagerer’s two part-time jobs—one in Greenwood, another in Fremont—along with the shows her punk band Mommy Long Legs frequently played at house venues in the U District, made getting around easy for the two of them.

When the time started drawing near, their landlord told them they could renew their lease for a third year, and everything seemed peachy. In June, less than a month before they were set to re-sign, the landlord informed them that (surprise!) he was putting their house on the market. They had two choices. “We could either buy it from him for $800,000,” Heck says, “or just ‘wait it out.’ But we couldn’t really ‘wait it out,’ because that just meant when someone bought it, we’d have to leave with almost no notice.”

But, inadvertently, they did end up waiting it out—for three months. The reason: Finding another place within their budget turned into an epic, disappointing saga.

“I’m not kidding when I say we looked at somewhere around 100 places,” Kagerer says.

“And we went in person to see at least 20 of them, probably more,” Heck says, “almost all of which people were fighting for.”

As time wore on, the couple’s Craigslist search filters started ticking up—first the price max, “$1,600, $1,800, until we got to our limit, $2,000” Heck says—then the geographic circle around Seattle began to expand. “We wanted something northside because of work and the band,” Kagerer says, “but we weren’t even really finding anything in south Seattle, and nothing on Capitol Hill was big enough to fit the giant photo printer we have, or our drawing tables.”

When a three-bedroom house on 150th in Shoreline popped up in September, they say it was a “might as well go see it, it doesn’t really matter anymore” situation. “At that point we just really needed a place,” Kagerer says. But to their surprise, they ended up loving it. For $1,850, the couple and their friend tripled the amount of space they’d had at their previous house. The two-story house included a fenced-in full backyard, and the couple was able to turn the third bedroom and the garage into art studios—“having all of our own space without shitty downstairs bro neighbors is amazing,” Heck says.

As for Shoreline? “It’s more neighborhoody” than where they were in North Seattle, Kagerer says, “and way more diverse, which is nice.” The two have been enjoying the park across the way, busy with families using the track, soccer field, and skate park. The Crest, a nearby $4 movie theater, has also been a big plus. But beyond that, “We honestly haven’t explored Shoreline as much because we’re still so close to Seattle; we’re basically right by Northgate,” Heck says. The two still eat at all their same favorite places in Seattle, and even though they’ve bought a second car (due more to Heck’s new job doing package design at Pokémon in Bellevue than to the move), they still bus into town a lot. On a Saturday, it’s only a 20-minute ride down to the Pioneer Square studio where Heck co-runs his indie publishing house, Cold Cube Press. “It’s cheaper to bus than to drive in and pay for parking downtown,” he says, “I don’t regret the move at all.”

“I miss being able to walk to a grocery store or coffee shop,” Kagerer says; “you kind of have to drive now. And being a mile from Greenlake was nice. But because we have a car now, it’s kind of like … ‘meh.’ It’s not really a big deal at all.” Turns out surprises can be cool after all. KELTON SEARS

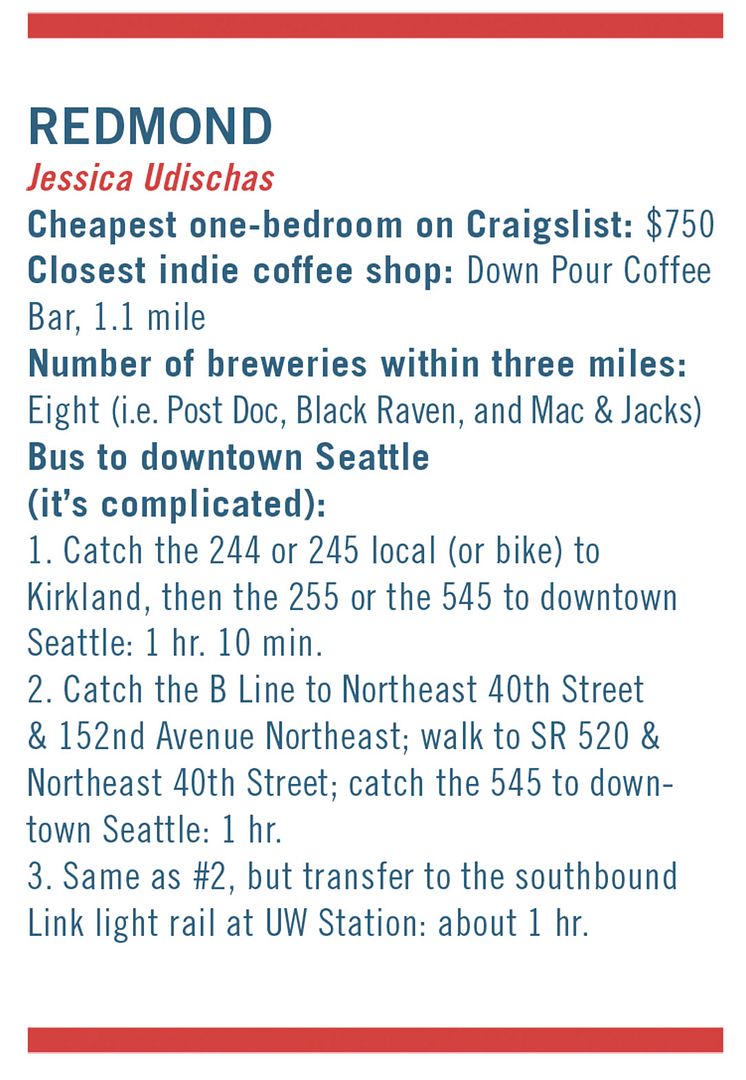

Jessica Udischas is best known for her semi-autobiographical web comic Manic Pixie Nightmare Girl.

“I started it because of the frustration of living as a trans woman in this world,” she says. Udischas moved to Seattle from Chicago in 2010 to escape brutal winters and plug into the Emerald City’s queer community, she says. “I remember when I moved to Seattle seven years ago, people were saying, ‘It’s over, they’re making this place for rich people only,’ ” she recalls. Which was true then and truer now, she says. Over the years, the rent kept climbing and the city kept changing, until the day came when the marginal costs of living here began to outweigh the marginal benefits of remaining. Now she too is an Emerald exile—to Redmond, of all places.

The Microsoft suburb is not exactly known as a bastion of affordability, and it’s not where Udischas expected to land, she says. But it’s the one she found by subletting from a friend and then taking over their lease. “The only reason we got this place is because we knew somebody,” she says. “We’re really lucky.” It’s within walking distance to a grocery store and pretty close to her partner’s workplace.

Udischas spent her Seattle stint living in a house near 21st and Union in the Central District, right by Chuck’s Hop Shop and Central Cinema. Now she lives in the cultural desert of corporate sprawl, surrounded by roads and reiterations of Chipotle, Safeway, and Starbucks. “I miss going to the local cafe and talking to my neighbors,” she says. “That was the big thing—we had Katy’s coffee shop on the corner. One of my roommates worked there, and a lot of friends from the neighborhood would hang out there. It was a nice place to go. There’s nothing like that here. I’ve become much more of a homebody, more isolated.” She’s gotten better at brewing her own coffee, she says.

“Compared to others, I feel really lucky. Most of the people I know who got pushed out of the city are having a harder time because they moved to an area where it’s harder to get to a grocery store, it’s harder to have community because the suburbs aren’t as populated. That’s the big thing I’m missing, is community and other people. As far as living space goes, I feel like I’m one of the lucky ones, because it’s a cozy place. A lot of my friends aren’t as lucky. They live in Renton. I have another friend who now lives in someone’s basement in the suburbs, and it’s not good at all. The bathtub’s all moldy and gross.”

Like a lot of millennials, Udischas doesn’t have a driver’s license, so she depends on rides from friends and public transportation when she wants to return to civilization from the hinterlands of Redmond. The trip takes a little over an hour on two buses. It’s doable but unpleasant, and turns any trip to Seattle into a logistical event. “In Seattle, it was easy for me to go to an art meetup or trivia night,” Udischas says. “Now it’s this big production. A ‘Night Out,’ as opposed to just a night in the city.” CASEY JAYWORK

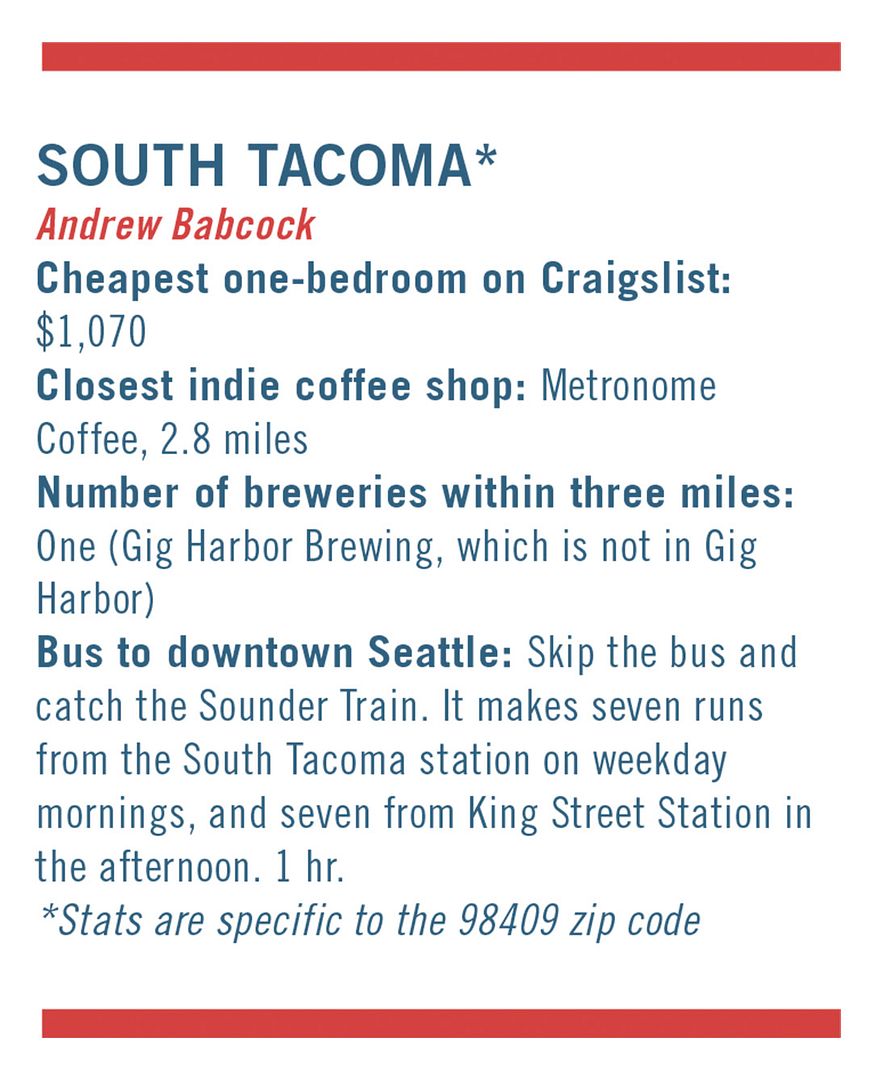

As they do, when Seattleites think about making the move to Tacoma, they often get on the Tacoma subreddit and ask what neighborhoods they should consider. As it does, conventional wisdom usually wins out in the comment section, along the lines of: Always look north and west; never look south and east.

For the geographically uninitiated, Tacoma juts north into Puget Sound like a finger poking you in the eye. Its northwesternmost point is Point Defiance Park, a vast stand of old-growth forest—with a beach and a zoo mixed in—that puts anything in Seattle to shame, Discovery Park very much included. And indeed, the North End and westside neighborhoods that are closest to Point Defiance can, to a Seattle homebuyer, feel like perfect Wedgwood facsimiles with a couple hundred thousand dollars lopped off the asking prices. South and east Tacoma, meanwhile, can feel like a stereotype of a Seattleite’s picture of Tacoma.

But who wants to live in Wedgwood? As a Tacoma resident myself, to my mind the real action in Grit City right now is on South Tacoma Way, where a cadre of young business owners with a little bit of capital and a lot of elbow grease are doing things that, frankly, Seattle prices would make impossible. To wit, meet Andrew Babcock, co-owner of Edison City Alehouse.

Babcock was a 12-year Seattle resident when he and his business partner, Robert Bessey, set out to open their own bottle shop—“a couple scrappy entrepreneurs looking for opportunity wherever it presents itself,” as he puts it. Naturally, their search began where they lived, but they quickly realized that the Seattle market would not accommodate their vision. “We started looking in Seattle primarily, specifically south Seattle, Columbia City, and surrounding areas,” Babcock says. However, “Most of the Seattle situations we considered would have required three to five times more money for the same business model. We had limited capital and resources, but wanted to create a bar that was ours”—as opposed to bringing in a bunch of investors who would then have a say in how they ran it.

With Seattle out of the question, they started looking elsewhere: Bellingham, Bellevue, “even Spokane.” But they ultimately settled on South Tacoma—a two-story building on 56th Avenue South just off South Tacoma Way, where Babcock could live upstairs while helping to run the business downstairs. That was in 2015; two years on they’re still pulling beer for a devoted clientele.

At first blush, South Tacoma Way may seem the wrong neighborhood to be slinging carefully crafted microbrews from 14 constantly rotating taps, as Edison City expertly does. The street name lent Neko Case the title of one of her more desolate songs, and the strip still oozes the gritty, working-class vibe that Tacoma has long been known for. Yet Babcock and Bessey are not the only young entrepreneurs taking advantage of the cheap and available space it has to offer. Around the corner from Edison City is Mule Tavern, where Sam Halhuli crafts his own ginger beer for delicious Moscow Mules; a block from there, three young entrepreneurs have purchased the shuttered Airport Tavern and plan to reopen it soon with live music onstage and paninis on the menu. “With the gentrification that’s happening around Tacoma, it seems like South Tacoma Way is going to be the final frontier,” Airport Tavern co-owner Dan Rankin told Tacoma Weekly. In other words, South Tacoma is a hotbed of what’s a dying breed in Seattle and parts of Tacoma: places where young people can take a risk on starting the business of their dreams without major financial backing.

Of course, part of the reason Seattle is such a hot market right now is that there’s so much money to be made. Babcock notes that “business runs a little slower in Tacoma,” but adds that’s “more my speed.”

“It’s more blue-collar,” he says. “I feel like people genuinely take more time to get to know you when you’re sitting in the barstool next to them.” DP

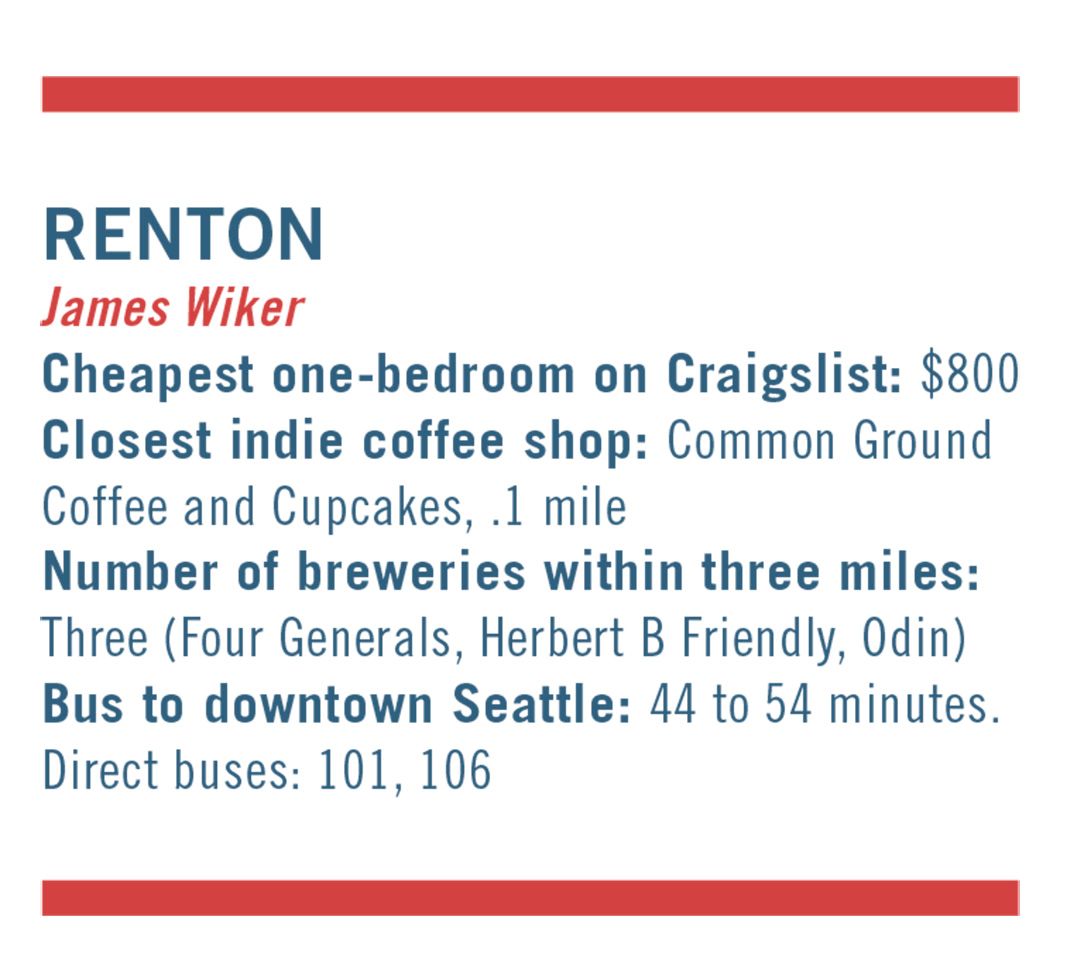

When James Wiker moved into his U District apartment 14 years ago as a UW undergrad, he had a sweet deal. In exchange for his onsite management work, he was able to live in a one-bedroom apartment rent-free. As the years went by, the value of his labor stayed relatively flat, while the Seattle rental market went through the roof. As of last fall he was paying $1,200 per month in addition to his landlord duties, which he juggled along with running a start-up bike-repair business. It was not sustainable for a number of reasons.

First, the obvious: He wasn’t a college kid anymore. “I was 33 and everyone was 18,” he says. “It was so weird. I felt like everybody’s dad. I was literally showing students how microwaves work.” On top of that, he and his girlfriend were looking to move in together, but student housing wasn’t going to cut it. And finally, Wiker had an opportunity to expand his small business—a traveling shop that catered to corporate clients, including Seattle Children’s Hospital and Facebook—into a brick-and-mortar space in Wedgwood and was conscious about his own cost of living. “Being in the bike industry, I feel an obligation to keep my labor prices low, because cycling is an activity that I think is inherently good and it’s something I would like to be accessible to everybody,” Wiker says. “Part of the expansion was to make sure I didn’t have to pay myself a lot of money to survive, so I could pay my employees and pay the rent and keep the store open.”

With Seattle housing out of the question, they looked to Renton, where Wiker’s girlfriend works as a teacher. There they were able to find a one-bedroom apartment about the same size as Wiker’s U District abode for $850 a month. While the hustle and bustle of the Ave was now 15 miles away, there were quirky locally owned shops and bars downtown, as well as easy traffic and ample parking. “It’s bizarre, but there is parking,” he says. “Even the bars have parking lots, which just seems like a lawsuit waiting to happen to me. You can get anywhere. It’s never crowded. When I’m driving in Renton, I never feel like I want to murder the person in front of me. It’s blissful.”

That is not the case when Wiker leaves the city limits, which he must do every working day. He now spends two to two-and-a-half hours a day commuting by car to his Wedgwood bike shop, Mend. He estimates that he spent $50 a month on gas when he lived in Seattle; now he spends $50 each week. He has also paid a physical toll: back problems from all that sustained sitting. And he gets less sleep, he says. Food is another issue, with Wiker calling his new home a “fresh-food desert.” “I don’t want a Whole Foods on every corner,” he says, “but it would be nice if you could get a carton of strawberries without half of them being rotten.”

But the benefits of living in Renton appear to outweigh the costs, as Wiker and his girlfriend recently bought a house, something he says he could have never afforded to do when he was in Seattle.

Still, the strains of living and working in two different places are there. “I don’t regret it,” he says. “But it feels strange, because being a small-business owner, I make jobs, I’m contributing to the economy, I pay taxes. My money stays in Seattle, but I’m not making enough to be a part of the community I serve.” MARK BAUMGARTEN

news@seattleweekly.com