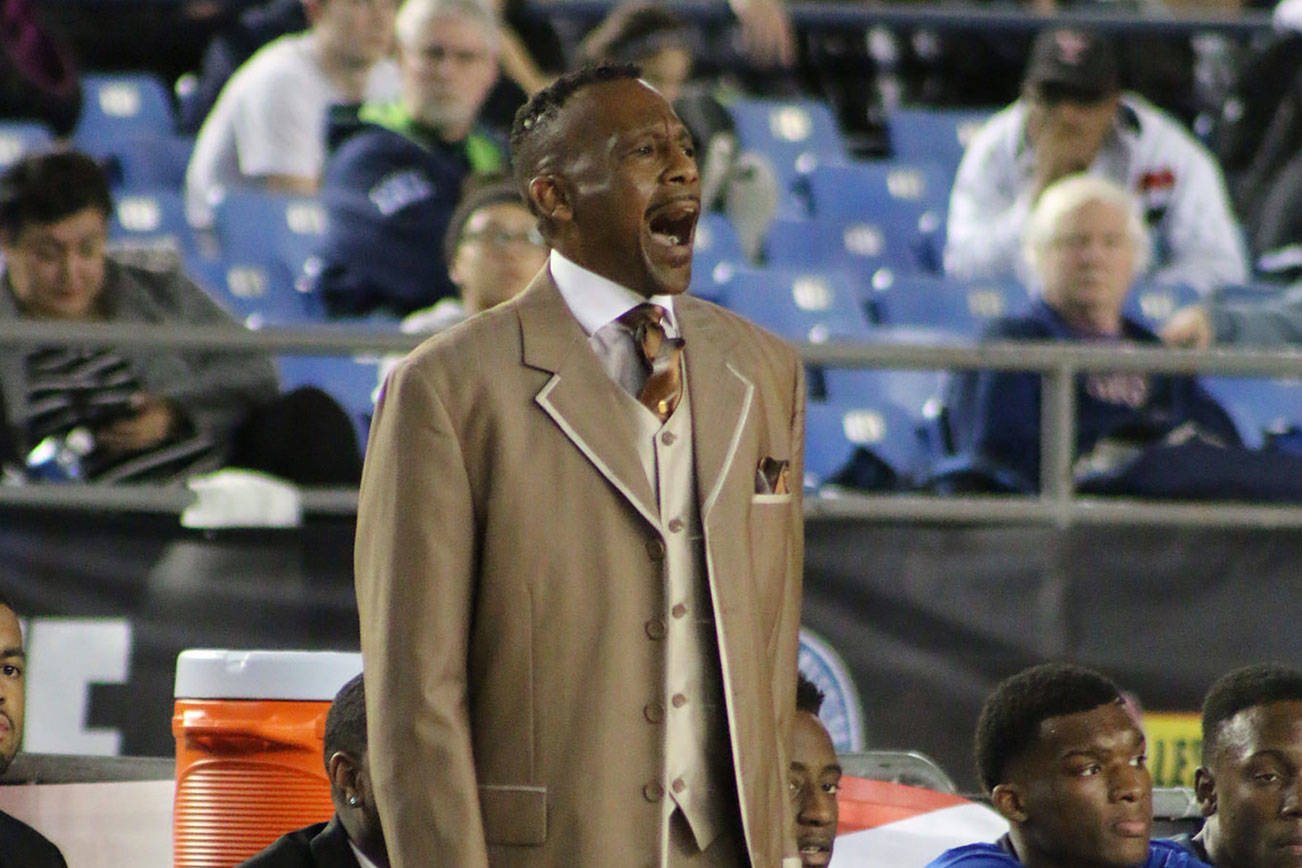

When Seattle Weekly first contacted Lincoln Beauregard, one of the attorneys suing Seattle Mayor Ed Murray for alleged child molestation and rape, he was getting onto a plane to fly to Japan for a few days to visit a friend. “Don’t worry,” Beauregard assured when asked when he would return to the U.S. to talk on the record—he has an international phone plan and is always available.

It was a fitting response for a local attorney who seems to be everywhere in local media of late, and not just because of the Murray lawsuit. Beauregard is also representing the woman suing Deadliest Catch star Sig Hansen over allegations that he molested her as a child, and he successfully represented law enforcement officers in two well-publicized cases in the last two years. The week after the Murray allegations came to light, King County reached a $1.34 million dollar settlement in one of those cases, brought by current and former deputies represented by Beauregard (with co-counsel Julie Kays) who claimed they were wrongly terminated. In a press release about the settlement, Sheriff John Urquhart acknowledged that Beauregard and Kays had won a jury verdict for $2.8 million against the City of Seattle last summer over a Seattle Police Department Officer overtime pay dispute.

The point being that when facing Beauregard in a lawsuit, it made sense to settle out of court, regardless of the facts of the case. It was a subtle and begrudging tip of the hat to Beauregard’s legal prowess from the sheriff, and spoke to the kind of profile Beauregard likes to keep: high.

Others squaring off against Beauregard have been less impressed by his penchant for publicity. In a court filing Tuesday, lawyers representing Murray asked for financial sanctions against Beauregard for allegedly misfiling court documents for the purpose of grabbing media attention, failing to file subpoena notices to the defense council before sharing the documents with the press, and using inappropriate language in his correspondence with Murray’s lawyers. In the motion, Murray’s lawyers claim that Beauregard has made “personal attacks” against them in the letters, going on to state that “Since initiating his lawsuit, Mr. Beauregard has filed letters” with the court “for the sole reason of hoping that the press would discover them. In other words, he has used the Court in order to generate publicity surrounding this case.”

Jeff Reading, Murray’s personal spokesman, concurred in an email to Seattle Weekly in response to questions about Beauregard. “Lincoln Beauregard has made numerous false and sensational claims in the course of this lawsuit, and has taken great pains to publicize them far and wide.”

But there’s little doubt that he’s effective.

In addition to taking on county and city bureaucrats, Beauregard has won cases against the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services involving child abuse and molestation, and the State of Washington for child abuse by state-appointed guardians. His successful cases rake in anywhere from hundreds of thousands to several million dollars in settlements.

“Lincoln has become pretty famous amongst lawyers as a successful plaintiff trial lawyer,” said Noah Davis, a managing partner at the Seattle-based In Pacta law firm and long-time friend of Beauregard. “I would put Lincoln in the top 20 statewide.”

“The guy is like Rain Man,” Davis added. “Lincoln is truly remarkably gifted.”

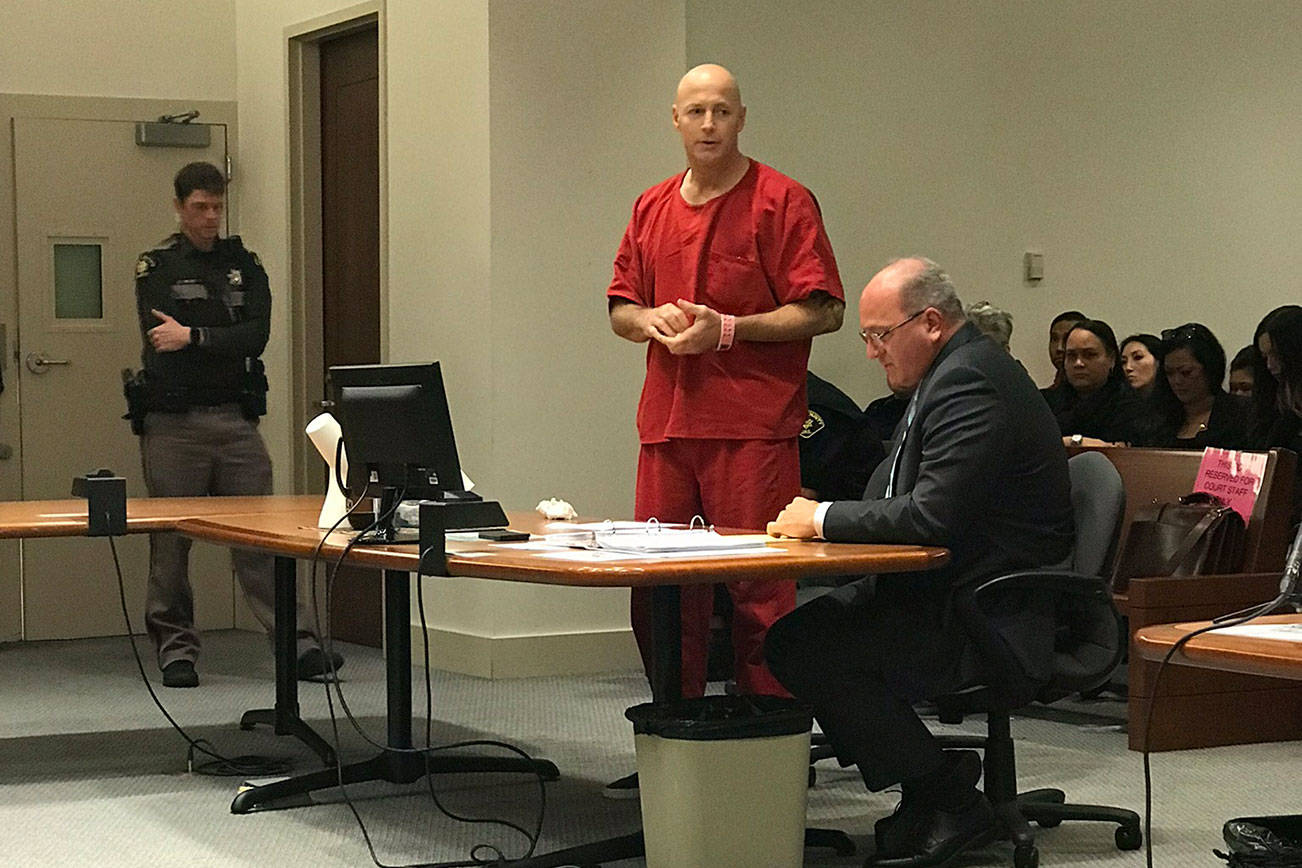

At age 44, Beauregard now finds himself taking on the most powerful figure in Seattle politics, Murray, by representing Delvonn Heckard, a 46-year-old man from Kent, Washington, who is suing the mayor over allegations that Murray molested him 30 years ago when he was a drug-addicted minor. The case has rocked the Seattle political landscape as Murray ramps up his reelection bid.

Beauregard is a little vague when asked about his motivations for taking on cases that target those in charge. He jokingly related an anecdote from his time as a student at Roosevelt High School: He got suspended after being falsely accused of punching another student. “Maybe that’s where it all starts,” he laughs. “I think I have a little bit of a healthy chip on my shoulder from my background.”

“I try to take on cases that involve the abuse of power,” said Beauregard. “It’s just the right thing to do.”

The suspension, along with a general loss of “interest” in school at the time, led Beauregard to drop out of high school when he was 15 years old. He got his G.E.D at South Seattle Community College in 1988, then quickly enlisted in the Air Force at age 17 to be an “air transportation specialist”—a job that basically entails the loading and unloading of cargo from military aircraft—and served for eight years at various bases around the world. Having earned his bachelor’s degree while on active duty, he was accepted into the University of Washington Law school when he got out of the military.

He originally wanted to be a prosecutor, but his focus changed when he was interning at the Seattle-based Gordon Thomas Honeywell law firm and was exposed to the types of cases that he takes on now. Beauregard cited a case where Jack Connelly—at the time a well-established lawyer with Gordon Thomas Honeywell—settled with the Puyallup School District for $7.5 million while representing the families of children who experienced racial discrimination in district schools. He loved the way Connelly handled the case, and wanted to do the same. In 2002, after graduating from UW Law, Beauregard became an associate at the firm. Four years later, in 2006, Beauregard left Gordon Thomas Honeywell and partnered with Connelly to found Connelly Law Offices with offices in Seattle and Tacoma.

Despite his frequent role taking on state agencies—DSHS is his most frequent opponent—Beauregard maintains that he hasn’t made any enemies within local bureaucracies; “probably just the mayor at this point,” he said.

“I don’t know how much the sheriff or chief of police like [me] but you’d have to ask them,” Beauregard added. (Urquhart declined to comment on Beauregard’s record, as did the lawyer who represented the county in the wrongful termination case.) Beauregard also donated to Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson’s 2016 reelection bid despite having worked against him in the court room. “I love the work that he’s doing,” he said.

Beauregard is somewhat unorthodox in his professional conduct as an attorney—and at times a little sloppy. Right after the news about the Murray lawsuit broke, Beauregard was defending his lawsuit in the comments section of a blog post at The Stranger. When Beauregard unveiled the name of his client, Delvonn Heckard, he misspelled ‘Delvon’ repeatedly in a letter to opposing counsel. (“It was the first time I [typed] his name,” Beauregard said when asked about the errors.) In a letter responding to the recent motion for sanctions filed by Murray’s lawyers, Beauregard said Robert Sulkin, one of Murray’s attorneys, has a “nasty” reputation.

Some lines in Beauregard’s court filings seem written for the tabloids. For example, in a letter requesting Murray sit for a deposition, Beauregard asked Murray’s lawyers, as an aside, to “confirm that Mayor Murray has the noted mole.” This was in reference to a mole Heckard says he remembers Murray having on his genitals, a salacious detail Murray later refuted with a doctor’s note stating he had no mole.

“I don’t have a whole lot to say other than that the facts are what they are,” Beauregard told Seattle Weekly. “If people want to spin it [my style] as unorthodox I invite them to look at my track record.”

The latest legal drama in the Murray case came on Monday, when Heckard’s co-counsel Kays filed a subpoena document in King County Superior court alleging that Murray, Seattle Police Chief O’Toole, and a Murray political staffer engaged in a cover-up over an incident at Murray’s Capitol Hill house on a summer evening last year; the subpoena cited an anonymous source claiming that, after Murray called Chief O’Toole directly to report an unknown individual at his front door, officers who arrived at the scene found a shirtless man who said he needed to recover his keys and clothing items from Murray’s residence. It also suggested the mayor was drunk. (Murray’s personal staff contest this narrative, saying that multiple witnesses can corroborate that the individual in question on the night of the incident never entered Murray’s home and grew aggressive after being denied entry to use the bathroom.)

Beauregard said that the relevance of this subpoena over the summer incident—which was cited in the opposing counsel’s motion over Beauregard’s conduct—is irrelevant. “We aren’t making allegations at this point, we’re in discovery right now, and whether it is admissible to trial is a separate question,” he said.

“We aren’t trying to prove anything about what happened at his house that night, we’re trying to get answers about his political apparatus,” he added. When asked to explain what he meant by “get answers about his political apparatus,” Beauregard said: “We’ll elaborate at trial.”

Murray’s corner is slamming Beauregard as using public-relations tactics with the press to undermine the Mayor’s public image.

“From trolling the comment threads of blogs and running an ongoing commentary on his Facebook page to conducting near-daily press interviews and sharing subpoenas with reporters days before the actual individuals being served, Lincoln Beauregard seems more intent on prosecuting his case in the media rather than a court of law, which makes sense, since he has no evidence to support his case,” Reading, the spokesman, said. “The seemingly damning description of the Mayor’s anatomy has been proven false by a medical doctor, and the seemingly damning production of the Mayor’s telephone number and apartment layout from 30-years-ago proves only that the internet exists. Both can be found online in about 90 seconds,” Reading added.

Aside from vehemently denying the allegations against him, Murray and his lawyers have painted the lawsuit against him as a politically motivated witch-hunt aiming to take down an openly gay mayor who championed marriage equality during his tenure as a state senator representing Capitol Hill in Olympia. Murray doubled down on this stance by penning an editorial in The Stranger titled “The Motivation is Political,” pointing to Jack Connelly’s $25,000 donation to the failed “Just Want Privacy” state ballot initiative (this initiative, if it passed, would’ve repealed statewide protections for transgender people to use public restrooms that match their personal identity), as evidence that the suit has a political angle. (Murray also claimed in the Op-Ed that Gary Randall, president and founder of the socially conservative Faith and Freedom Network and vigorous opponent of Murray’s work on LGBTQ rights, has used the other molestation allegations in the past to attack Murray.)

Beauregard, who says he strongly disagrees with Connelly on social issues such as transgender rights and marriage equality, denied any conservative or anti-LGBT connection or backing behind the suit.

“As much as it is annoying to be a focus of this false insinuation, it is also entertaining and laughable,” Beauregard said. “They have no basis for accusing us of being anti-gay.”

“[Connelly] is a great guy. We just have a different view on some of those issues,” he added. “We started the firm together but he doesn’t have any input in what cases I even file.”

Beauregard called the question of whether the lawsuit has any anti-LGBT connections is beside the point, saying that “if an anti-gay group came to me and said ‘I want you to represent these molestation victims against someone in a position of power’ and if I vetted the case and found out it was true,” that he would take the case.

Then, without missing a beat, he went back on the attack.

“It [Connelly’s personal views] doesn’t take the issue off the table that the mayor is a child molester,” he said.

jkelety@seattleweekly.com

This story has been edited to clarify the circumstances of Beauregard’s suspension from high school.