Last week, Michael Volz was walking home from a Capitol Hill benefit show for the victims of the Orlando mass shooting when a random stranger beat and choked them bloody and unconscious. “Show me your tits, you tranny cunt!” the attacker reportedly cried.

Speaking at a press conference on Friday with bruises and scabs surrounding their right eye, Volz said, “This is not an isolated incident. This is something that happens to our community frequently.”

Volz is correct. The Seattle Times’ Gene Balk reports that hate crimes against queer Seattleites doubled from 2014 to 2015 (as they also did against black Seattleites). While this uptick may be caused in part by improved reporting of hate crimes to police, queer people are at least 50 times more likely to be targeted than members of Seattle’s white population as a whole, Balk reports.

But while the problem is clear, solutions—beyond constant reminders that all humans deserve dignity and safety—can be elusive.

In the fallout after Volz’s attack, some questioned whether the city has done enough to protect its LGBT denizens. After all, this isn’t an especially novel problem. With gentrification eroding the soul of Capitol Hill, Seattle’s longtime gayborhood, queer activists have been ringing the alarm bell on hate violence for years. Yet the increased attacks come at a time when the city seems to be doing more to combat anti-LGBT crime.

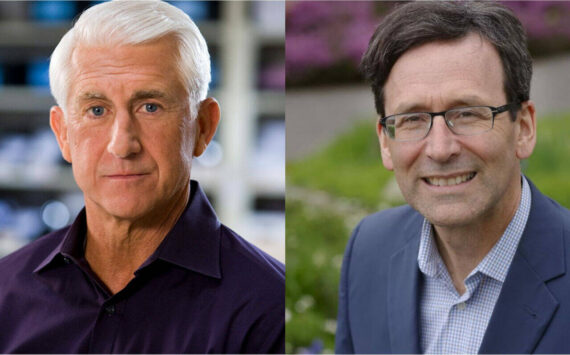

Last year, Mayor Ed Murray—who pushed groundbreaking LGBT legislation through the state legislature as a representative and then senator prior to his current gig—convened an LGBTQ task force that tackled, in part, ways to reduce hate crimes. Its July 2015 report includes several recommendations to the city to increase safety for queer people on Capitol Hill and in Seattle generally.

Since then, Seattle has added $20,000 in small-grant money to the 2015 adopted budget via the Neighborhood Matching Fund, $40,000 for LGBT homeless youth services, $30,000 on public education and outreach, and $75,000 for cultural competency training for caregivers of LGBT elders. All told, the adopted 2016 budget includes $165,000 earmarked for task-force recommendations. Obviously that money won’t eliminate anti-queer violence, but it’s not nothing, either.

Murray also points to the city’s Safe Space program, which consists of rainbow stickers that businesses and other entities can put in their front windows to advertise their sympathy with victims of bashings. Businesses with stickers are supposed to call the cops if they see an attack, and to allow victims to wait inside until police arrive. But while the city can boast of widespread adoption of this program, police say they don’t track the use of Safe Spaces by queer people who have been or fear being attacked. “I’ve got so many applications, I can’t keep up,” much less collect and sort data on their use, says Jim Ritter, SPD’s LGBTQ liaison officer and creator of the Safe Space program.

Safe Space did not help Volz. They were attacked in the heart of Capitol Hill near several Safe Space locations, but instead of going into one for help, Volz opted to go home. This one example doesn’t show that Safe Spaces are a failure, but it does raise important questions about the program’s efficacy, since Volz’s bashing was exactly the kind of incident Safe Spaces are supposed to address.

So there’s room for improvement. Still, the mayor and other city leaders deserve credit for paying more than lip service to the plight of queer Seattleites.

And at the end of the day, officials can do only so much. It’s up to us, the people of Seattle, to decide whether we want to live in a city that’s safe for queer people. This is not an abstract decision, but one made in the split-second choices that daily life comprises. When we hear a slur on the bus, when we see an assault on the street, when we fill out our ballots, when we show up to meetings and parades: These are the moments in which we all continually create the world we live in. Will we live in a city where bigotry is a fact of life? In Volz’s own words: “You have to reach out and ask your community for help. We’re united. We’re not going anywhere. We’re a strong community. We don’t back down, and we support each other.”

editorial@seattleweekly.com