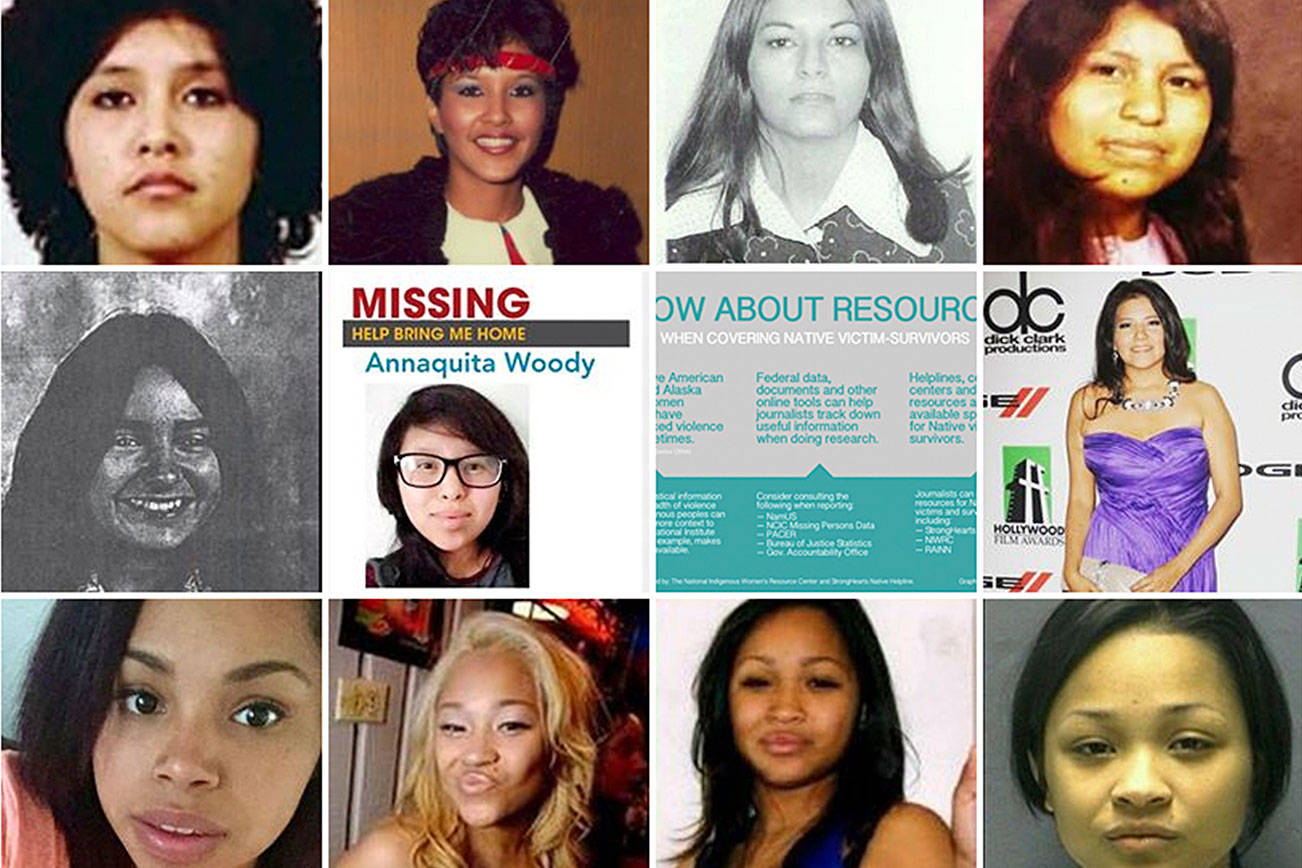

Last week, the Urban Indian Health Institute published a report that showed the pervasiveness of sexual violence among Seattle’s Native American women. The results revealed that 94 percent of the 148 self-identified American Indian or Alaska Native women surveyed in 2010 had been raped or coerced into sex, and only 20 percent of them reported the attacks to police.

The sobering statistics hit close to home for many Native women. City leaders even weighed in to voice the significance of the report.

“This will be the first of many discussions that will take place around sexual violence in our community,” Seattle City Councilmember Debora Juarez said in a statement. “We have always known that the rates of sexual violence against Native women was high, but it’s going to take others to acknowledge it as well and to do something about it, and that needs to happen now.”

Indigenous women are over two times more likely to experience sexual violence than the rest of the public. The reasons for such high rates of abuse and lack of accountability are layered and complex, partially rooting from the historical trauma of colonialism, according to Esther Lucero, CEO of Seattle Indian Health Board — the nonprofit that oversees the Urban Indian Health Institute. Defined in the report as the “cumulative emotional and psychological injury over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma and a history of genocide,” historical trauma can manifest as cycles of violence in which the perpetrators are often survivors of abuse themselves.

“It’s significant because it’s one of the things that causes shame and guilt, and keeps people from talking about it, or holding people accountable,” Lucero told Seattle Weekly. Historical trauma is so intertwined with sexual violence, in fact, that 86 percent of the survey’s respondents reported being impacted by the phenomenon.

Lucero believes that boarding schools, which sought to assimilate Native communities by stripping them of their traditions, “is where our family systems became dismantled.” It resulted in shame, guilt, and a silencing of violences, which Lucero argues has bred a normalization of sexual abuse and a lack of accountability. Colonization also incited the dehumanization of indigenous women, creating a “culture where women are less valued and thought of as property,” she noted.

The results were so apropos to a culture of silencing that they remained tucked in a desk for six years until Lucero and Abigail Echo-Hawk, chief research officer of Seattle Indian Health Board, replaced two men on the team and brought the results to light.

“I think that it’s important to note that both Abigail and I are Native women,” Lucero said, “and these stories come forward when people with those lived experiences help share them.” She added that the data needed to be revealed by women in order for trigger points to be properly addressed, as well as to create safe spaces and resources to support the survivors’ healing.

Lucero said that the low reporting rate to the police — with only 8 percent of rape victims’ first attack resulting in a conviction — has demonstrated a distrust of Western communities. It highlighted the “importance of having organizations like ours to have women be able to talk about this in their own way,” she continued.

The report also revealed a need for culturally appropriate responses to sexual violence, Lucero noted. One source of program funding is the Violence Against Women Act, which provides federal grants for state, local and tribal governments to address sexual assault and domestic violence. The legislation is up for renewal in September, and if approved by Congress, it would reauthorize the act for another five years.

Publication of the data has since sparked community conversations about the epidemic, and the need for greater research to accurately assess the widespread nature of sexual violence. “It’s about us healing as a community and addressing all of the aspects of this problem,” Lucero said.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com