“Whenever I go anywhere, I walk in with seven kids,” started Kittitas County resident Jessica Hanna with a chuckle, “So it’s kind of crazy.” While the 32-year-old is on the Washington Capitol steps as an advocate, she’ll momentarily take a pause from her disarming verbal barrage of Central Washingtonian “oh gollys” to warmly gaze at kids playing tag on the Capitol lawn or chastise children for climbing atop unsafe structures. Hanna became a foster parent about 11 years ago when she assumed custody of her cousin’s baby, only to later adopt him and some of his siblings. Her passion for care-taking led her to recruit other parents into fostering. But after several years of fostering, she noticed a culture of fear within the system that was pushing out foster parents and creating greater case loads for social workers as a result.

For instance, Hanna said that a social worker attempted to move one of her foster children out of her care while Hanna was in labor about three years ago, even though the workers didn’t have a contingency plan for the child. “And I’m anti-moving kids until they have permanency, whether they go back to their birth parents, [or] whether it ends in adoption,” Hanna said, “but moving kids is like the worst thing you can do.” Hanna wanted greater oversight within the foster care system to prevent such acts of intimidation.

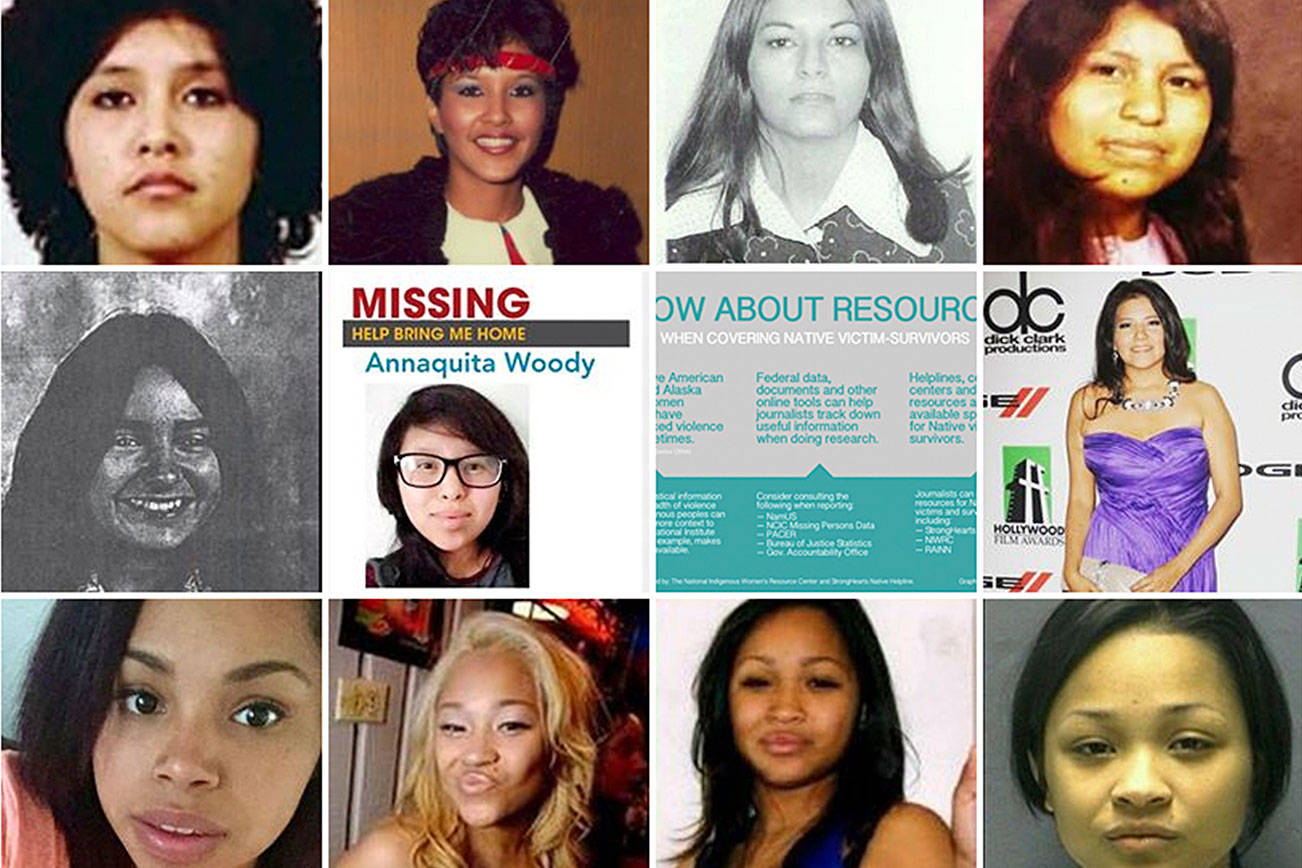

The beleaguered system has had ripple effects. According to an InvestigateWest report for KCTS 9 and Crosscut, the state lost one in five foster homes between 2008 to 2015. Moreover, the state says that the turnover rate for social workers is around 30 percent annually in King County.

Hanna’s personal experience, along with horror stories that she heard from other parents, inspired her to form a group called Fostering Change Washington. Founded a year ago, the organization advocates for the rights of foster parents in Washington.

On Wednesday, Hanna and about 100 other foster parents and advocates stood on the Washington State Capitol’s steps to rally in support of House Bill 1661, a law passed last year to transform the state’s foster care system. The law will merge the Department of Early Learning, foster care, and adoption programs into the new Department of Children, Youth, and Families on July 1, 2018. Juvenile justice programs will also be incorporated into the new department the following year. Fostering Change Washington and other advocates hope that the new department will streamline services through a prevention-focus lens, help families reunite, and provide greater support to foster parents.

The law was born out of a 2016 study conducted by a bipartisan panel established by Governor Jay Inslee called the Blue Ribbon Commission. The panel spoke with families and social workers within the Department of Social and Health Services and found that state services were not organized in a way that achieved the best outcome for children and parents. Instead, they recommended a single streamlined department that focuses on early childhood development.

HB 1661 will define outcomes for the department and create mechanisms for partnering with communities. An external review policy will also ensure that the department is reaching its desired goals.

Hanna supports the new bill, but plans to continue pushing lawmakers to create a family finding unit to locate foster children’s relatives. She wants foster families to be able to establish a relationship with the birth families, “so these kids aren’t getting plucked from their long term placement of foster care and being sent to a stranger, in essence.” Fostering Change Washington also held the rally to advocate for clear timelines to establish permanent placements for children through reunification with their biological parents, adoption, or guardianship by relatives. They also want a task force to create policy based on scientific studies about bonding and attachment. Ultimately, they want foster parents to have a greater voice within the new department.

Shanna Alvarez, a 36-year-old psychologist based in Seattle, also attended Wednesday’s rally to advocate for foster parent rights. She’s not a member of Fostering Change Washington, but has worked with the organization as a foster parent representative who provides surveys and consultations to the state’s Children’s Administration.

Although she’s had a positive experience with her social workers over the past two years, she says she’s seen the impacts of short-staffing lately.

“It’s an overburdened system, which means that responsiveness is low and … it’s very hard to get your voice heard,” Alvarez said. She and her husband have had to miss work to attend a court date that ended up being postponed. Another time her foster kids had a meeting with their biological mother who didn’t show up, so Alvarez had to leave work early to console the upset children. The high social worker turnover also impacts her life, because the entire system comes to a halt when replacements are trained. “There’s nowhere to turn for foster care advocacy,” Alvarez said.

It seems that foster care providers and social workers are also optimistic about the new department’s potential. Seattle-based foster care nonprofit Amara—which works with over 150 foster families and cared for over 100 children in King County last year—believes that the new department could create a more stable environment for children.

“We really empathize with the task that the state has to move forward on, which is to care for thousands of kids in our community,” said Amara Chief Operating Officer Megan Walton. “Our job … is really to support foster families, to support adoptive families and keep the child at the center of our work. And so if the department does result in a more stable workforce where social workers want to stay … I think more stability in the system can only mean more stability for kids.”

In an email to Seattle Weekly, Washington State Department of Social and Health Services spokesperson Norah West agreed with Walton’s sentiment: “With the creation of a dedicated cabinet-level agency come many exciting opportunities that will allow staff to support families differently, providing better access to services and better integration of those services.”

Although the new department’s policies are still nebulous, Alvarez and Hanna ultimately hope that the new system will incorporate more of their voices.

“You take these kids into your home and they are part of your family,” Alvarez said resolutely. “We are not foster babysitters, we’re not caregivers. We are a family. We are foster family.”

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com