One sunny afternoon last spring, Susana Lopez arrived at Roxhill Elementary School in West Seattle to pick up her third-grader, Melanie. She knew immediately that something was wrong. Melanie wasn’t her usual bubbly, school-loving self. She was very quiet, with shoulders stooped. She seemed exhausted and subdued. •“The first thought that came to mind,” Lopez says now, “was that maybe she was having problems with another kid at school, that someone wasn’t nice to her. Both my daughters are very sensitive.” But no, Melanie responded, it wasn’t that: “We were prepping.”

“You were … what?”

“We were prepping,” Melanie said. “It was frustrating.”

“What were you prepping for?”

“A test that’s stupid.”

“What test? I don’t know of any test. Was it, like, a surprise quiz that your teacher gave you?”

Melanie’s voice began to quaver. “I don’t know what it’s called, but it’s in the computer. It’s in the computer and we have to use the mouse. And it’s frustrating because sometimes it doesn’t move.”

And that’s when she burst into tears, Lopez says, and began pleading with her mother to let her stay home from school the next day. “Can I just please, this once, can I just please stay home? I never asked you to do this for me, Mom, please, can I please just stay home?”

Lopez told Melanie no, absolutely not. She was going to school the following morning. But she did promise to talk to her teacher about it. And so, the next afternoon, Lopez approached Melanie’s teacher—who is “an amazing teacher,” Lopez says, “my daughter loved him”—but all he said was that the kids were preparing for a state-mandated test called the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), and he was unable to discuss it.

“Does she have to do it?” Lopez asked.

“I can’t say anything about that,” he said.

Right away, Lopez says, that “put up the biggest red flag.” She wanted to know what the test was about, and whether or not Melanie was required to take it; it seemed to upset her so much, after all, and she usually adored school. But, strangely, “the one person I trust with my daughter’s education is not allowed to talk to me about this.” The teacher “didn’t say he would get in trouble” for talking about the test, Lopez says, “but I got that feeling.”

That night she spent hours researching the SBAC online. She learned that it is a Washington-state-mandated test, officially launched in 2015, that’s also being implemented in 16 other states, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and in Bureau of Indian Education-run schools. It’s designed to align with Common Core, a set of educational standards in literacy and math recently adopted by 42 states. When fully phased into the Washington public-school system, both the math and English language-arts versions of the SBAC will be mandatory each year for grades 3 through 8 and 11; passing it will also be a high-school graduation requirement.

But Lopez, like a growing number of parents, teachers, and students in Seattle and across the country, felt suspicious of the test’s value. SBAC test-makers expect 60 or 70 percent of students to fail their first time taking the test, which confused Lopez. She also believes that students for whom English isn’t a first language “don’t have a fair shot at it,” and questioned the corporate interests behind the tests.

On her hunt for information, she found something else: a Facebook page for a group called Seattle Opt Out. It’s a gathering place for parents, like Lopez, who are looking for more information about standardized tests and exploring their right to “opt out”—better known to state administrators and SBAC advocates as “test refusal.” Lopez clicked “Like,” and, emboldened by the movement she had just joined, marched into the Roxhill Elementary main office and, less than 24 hours after witnessing her daughter’s tears, handed Principal Sahnica Washington a signed letter saying that she chose to opt Melanie out of the SBAC that year. “I am set on my decision,” the last line read.

Shortly thereafter, at a parent meeting that Lopez believes was designed specifically to encourage skeptical parents to buy into the test, the principal confronted Lopez and told her that if Melanie didn’t take the test it would come back to haunt her in high school, that she wouldn’t be able to participate in certain district-wide programs, that she wouldn’t be able to graduate. “I felt like she was trying to scare me into doing it, kind of using my daughter as a pawn,” Lopez says. “Like, ‘Hey, you don’t love your daughter, because you’re screwing with her future.’ And when she thought that wasn’t really working, then she started telling me about losing funding” because student-participation rates in state-mandated tests can jeopardize federal education money.

The whole thing felt bizarre—and opaque. Lopez already wasn’t convinced of the value of the SBAC. The drama and coercion associated with it made her feel all the more alarmed. Lopez remembers being in the school hallway when another parent tried to discuss opting out with a teacher, who, during the conversation, “kept looking everywhere to make sure there was nobody there.” Just by “her body movements and her gestures,” Lopez says, “you could clearly see that she was uncomfortable.” Afterward, the other parent asked Lopez if she’d noticed that discomfort, joking that the conversation had “felt like a drug deal.”

“If teachers can’t talk about it,” Lopez says, the next question comes easily: “What are they afraid the teachers are going to say?”

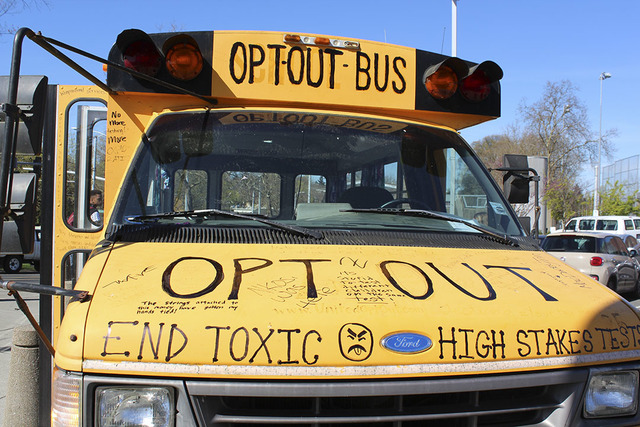

The “Opt Out” movement has gained a huge amount of traction nationwide. Challenging the prevailing wisdom—that tests scores correlate with both student aptitude and successful schools—more than 670,000 students opted out of standardized tests last spring, according to the National Center for Fair and Open Testing. While that’s a tiny percentage of all public-school students, in some states it’s begun to have a major impact: In New York, one in five students required to take state tests opted out last year. The activist group United Opt Out has chapters in almost every state.

The movement has grown powerful in Washington, too—particularly in Seattle. Last spring, at Garfield and Nathan Hale high schools, nearly 100 percent of 11th graders refused to take the SBAC. Across the city and state, 50,000 other students joined them, making it the fourth-largest walkout in the country—large enough to break federal law. The U.S. Department of Education requires a 95 percent participation rate in state tests; that was the rule under No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the George W. Bush administration’s signature education law, and remains so under the renewed Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). In December, Washington was among 13 states to receive an ominous letter from the feds, threatening to remove federal funding if they did not improve participation rates this year.

Yet prominent educators and activists Jesse Hagopian and Wayne Au; a crowd of very vocal parents, teachers, and students; and the Seattle/King County chapter of the NAACP have all joined forces here to actively protest what Nathan Hale history teacher Doug Edelstein calls “the testing regime.” A few weeks ago, at a press conference co-hosted by the NAACP and Seattle Opt Out, Seattle NAACP president Gerald Hankerson called on the school district to “eliminate or suspend” high-stakes tests. “These standardized tests … have drastically failed us for so many years,” he said, echoing the critique maintained by many in the opt-out movement: The tests discriminate against low-income kids of color, and guard the very achievement gaps they claim to narrow. “These tests are biased; they have no purpose in our schools.”

Opt Out has grown large enough to prompt a coalition of state agencies and advocacy organizations, called Ready Washington, to sling its own counterattack: “Opt In for Student Success.” Launched about a month ago, the campaign features videos of high-school students explaining why they’re taking the SBAC.

“Our mission is to build awareness and understanding and support for college- and career-ready standards and assessments,” says Chris Barron, communications manager at Partnership for Learning, the education arm of the Washington Business Roundtable and a key partner in Ready Washington. The “Opt In” campaign is about building student voice, he says; “We don’t hear from students enough.” “Opt In” is indeed “a play on the ‘opt out’ terminology,” Barron explains. “There’s a lot of negativity around test refusal, as we call it, or the ‘opt-out movement.’ We really wanted to create a positive, proactive, upbeat awareness campaign.”

There are good reasons to take these tests, state officials and testing advocates say; some laud the SBAC, in particular, as the pinnacle of testing design. It is computer-adaptive, meaning the questions get harder if a student answers something correctly and easier if he or she does not. While some educators debate the pedagogical value of that kind of test, it offers a “more precise measurement of the student’s skill,” says Robin Munson, assistant superintendent of Assessment and Student Information at the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI).

“We’ve always had a 95 percent participation requirement,” adds Munson. “And we’ve never had an issue reaching it until last year. We’re hoping that this is a short-term phenomenon and that parents will begin to understand that it is their right to know how their child is doing in school, and their right to know as a taxpayer how the school is doing compared to other schools. The only way we’re going to know that is to have a common assessment throughout the state,” she says. “It really is an equity issue.”

Fundamentally, says Wayne Au, a professor at UW Bothell and an outspoken critic of standardized tests, “all these guys want to do is make comparisons. Here’s the thing. It is harder to compare schools and kids and teachers” without standardized tests. But from his point of view, “I don’t care how [students] perform relative to Joe Schmoe in Issaquah or Bellevue. I just want them to be a fulfilled human being.”

But as long as the test-centered framework remains, so does the pressure: A score is still logged even if a student refuses to take the state-mandated test. It’s logged as a zero. So if a large number of students don’t take the test, a school’s overall average will plummet, impacting not only its access to federal dollars, but—given the association between high test scores and good schools—its reputation.

Opting out “gives a false picture of the quality of the schools,” says Munson. “Our performance on state assessments … is used by the public as people are deciding which home to buy, which schools to send their child to.” It also “may ultimately have an effect on housing prices,” she says. “I know when my parents moved from state to state, that’s how they picked where they were going to live.”

The emphasis on uniform education standards, high-stakes tests to measure student mastery of those standards, and the inherent value of a school with high test scores has dominated the public-education system for some time now—at least since the passage of NCLB in 2001. A recent report by the Council of Great City Schools found that kids in large, urban school districts across the U.S. will take an average of 113 standardized tests before they graduate from high school. In some school districts, 11th graders spend nearly a month of the school year taking tests (and in Seattle, many educators told me, that’s how long the computer labs and libraries can be booked solid for testing). A National Education Association survey from 2014 found that nearly half of public-school teachers have considered leaving the profession due to the overwhelming prevalence of standardized tests.

Of course, in the classroom, some form of assessment is crucial. “We want to know how we’re doing, so we can make adjustments and do what’s best for our students,” says Tracy Gill, a sixth-grade social-studies teacher at Denny International Middle School, where, last year, students who opted out of the SBAC were barred from attending the school’s year-end carnival. The preponderance and the pressure, though, is just “too much,” she says. “The kids are losing their desire to learn. There’s nothing to inspire them.”

Alison Yount has been teaching English to non-native speakers at Chief Sealth International High School for almost 15 years, and she says standardized testing has increased “incredibly” over time. Schools force students to “study to the test, have classes built around the test, take the test, and if you don’t pass the test, then you have a remedial class to help you pass the test. If you don’t pass the test, your options are … more tests.” Two of the classes she teaches now are devoted entirely to passing state tests. “I apologize for the classes I’m teaching because they’re grim,” she says. “That’s the thing that kills me.”

Yount argues that many of her students have just arrived in the United States; even if they don’t pass, “in every other respect they’re ready [for college or a career]. My students tend to be emotionally more mature. They have more life skills than your typical high-school kid. But they don’t get credit. They’re made to feel stupid.” Although much of the effort behind these big tests, ostensibly, is to close the achievement gap and help all students succeed, “I don’t see it helping,” Yount says. “I see it helping them hate school.”

Ikram Ali, a senior at Franklin High School, recalls one classmate who didn’t pass a state test the first time, saying, “ ‘I knew I wasn’t gonna pass because I’m stupid.’ It wasn’t just with her, but a whole bunch of other students, too,” Ali says. “They seemed to give up afterwards. They’re like, ‘What’s the point? I’m not gonna graduate now. I’m dumb.’ This is what standardized testing does to students.”

Indeed, for many opt-out parents and students in Seattle, the high-stakes pressure, the narrow definition of intelligence, and the resulting plunge in self-esteem is having an effect on student morale.

Shawna Murphy, a parent at Orca K-8 and one of the most active members of the local Opt Out movement, says her now-sixth-grade daughter’s scores from a district test in kindergarten “were laughable, they were so low.” But when, in third grade, she took the district tests again and her scores improved, that achievement was announced over the school loudspeaker. “I was so offended,” says Murphy. To announce “improvement” to the whole school felt like both an invasion of privacy and a troubling attachment of her daughter’s worth to a single test. “These scores were obviously so arbitrary. My daughter hasn’t become more intelligent since kindergarten.”

Murphy sees these tests as harmful, and the SBAC even more so, especially for kids with learning disabilities. Some kids are more familiar with a computer and a mouse than others. Students must toggle among many windows at once, and they are not able to skip a question and come back to it. The testing lasts days, if not weeks. Multiple parents have pulled their kids from the tests because of tears and anxiety; Murphy has heard scores of stories from parents of kids who had bad dreams and “regressive behaviors because they were so nervous about these tests.”

Heidi Alessi, also an Orca K-8 parent, says her fifth-grade son has ADHD and struggled enormously with the SBAC last year. “At first my thoughts were, you know, standardized tests are a part of life. Our kids are going to have to take them if they want to go on to college. Testing is here to stay, I get that.” But her son’s experience was so dramatic that she ended up opting him out. His school “spent all year talking about this test and getting prepared for it. He wasn’t sleeping, he was so stressed every day about the test.”

And that was just fourth grade. For high schoolers, required to pass these tests to graduate, it can be nerve-wracking. “I’ve seen students walking down the hallways having panic attacks,” says Payton Dannehl, a senior at Garfield.

And for now, anyway, the SBAC feels to some teachers, parents, and students like a lot of song and dance without much connection to learning. While assessment tools designed to help teachers incorporate the test into class curricula are built into the SBAC system, teachers aren’t using them much yet.

“The SBAC especially didn’t make any sense,” says Franklin High School junior Dureti Jamal. She took it last year, in 10th grade (it was offered to sophomores as a way to practice). There was “nothing in there that seemed like it was relevant to anything we were doing in school.”

And yet it is the one thing that must happen to make it to college. “You could have a 4.0,” says Dannehl, “and they would be like, ‘Oh yeah, you got good grades, but this says you’re not ready for the adult world. So you’re staying here.’ ”

“We don’t have a student problem in this system,” says parent Sebrena Burr, whose daughter is currently opted out of the SBAC. “When we look at these test scores, it’s not a student problem. It’s an adult problem that we’re putting on the kids, that tell them that they’re ‘less than’ at the most critical time. We’re giving them a tag: You’re bright and you’re brilliant, or you’re not good enough, you’re not gonna make it. And they’re buying it.”

While Gill, the social-studies teacher, feels that it’s incumbent upon teachers to speak up about testing, she confirms what Susana Lopez suspected: “We’re not allowed to talk about [the SBAC] to the parents of our students,” she says. Also, “We are told specifically that we can’t encourage or inform parents about how to opt out or the fact that they can opt out.” Teachers, she adds, are “constantly told we have to do what’s best for the kids—unless it goes against state testing.”

Nathan Hale’s Edelstein can’t name names on the record, but says he’s heard innumerable stories of teachers being at least verbally disciplined for speaking their minds. “Several principals have told individuals in the Seattle Public Schools to shut up about their opinions about testing and about the SBAC,” he says. “Which, of course, is a violation of our free-speech rights.”

Also troubling to many opt-out advocates: Although there are plenty of sample test questions and practice tests, teachers are not allowed to see the test itself. (In fact, no member of the public is; tests are one of the items exempt from public-records requests for OSPI).

Robin Munson explains that there are no “gotcha” items on the official tests, though, and security is important for validity. “If the items were not kept secure and people were able to share those items, we wouldn’t know that we have a valid assessment of what a student knows or can do.”

Along with federal and state laws requiring the tests, Seattle Public Schools has taken further steps to pressure students into taking them: One is access to the district’s accelerated-learning options, the “Highly Capable” and “Spectrum” programs. Students must apply to be considered, and beginning next school year, they won’t be if they opt out of the SBAC.

That notion is infuriating to many educators and parents. Making the SBAC a gatekeeper for advanced learning is “pure institutional racism,” says Edelstein, and “keeps [parents] out of the discussion of the validity of the test.”

Also at stake: Seattle’s 2011 Families and Education Levy, which funds all kinds of programs, including early education, school-based health centers, and programs designed to close the achievement gap. The city uses “performance-based contracts” to evaluate the success and value of a program, and bases them, in part, on student outcomes on standardized tests. That means that programs—even arts programs—can be defunded if they’re not tracking and improving test scores in math and reading.

Both Garfield High School teacher Jesse Hagopian and UW Bothell’s Wayne Au point to what they see as a searing hypocrisy in the emphasis on testing as the key to success, and to achieving equity: the first standardized tests in the United States were designed by eugenicist and white supremacist Carl Brigham, who developed the SAT as the price of admission to Princeton University. Standardized tests have been used in public schools ever since, Hagopian, Au, and others argue, to disguise privileges in race and class as personal merit.

The idea behind the testing system is that “if we just increase standards, that’s going to improve learning,” says Au. “There’s no research to back that up at all. That’s what we do in this country. We raise standards and assume that everyone’s going to do better and we never have this conversation about structural issues: homelessness, poverty, living wage, affordable health care, affordable housing, whatever. All these things that we actually know from research have a much stronger influence on student learning in school than any test we give them, any set of standards.”

These tests “don’t measure your intelligence, they don’t measure your aptitude,” says Hagopian. “They measure your access to resources.” In fact, “the thing that correlates best to standardized test scores is your ZIP code.”

According to Ready Washington, the explosion of opposition to the SBAC is based largely on a lack of information. “It takes a while to build awareness and understanding,” says Chris Barron. “There’s great value in taking the high-school assessment,” he adds, pointing out that it does have an actual financial value: In addition to being a graduation requirement—the class of 2018 must pass the English language-arts SBAC test to graduate and the class of 2019 must pass both the English and math tests—it also can, if students score a 3 or a 4, waive remedial coursework in college.

“We’re teaching college- and career-ready standards,” he says. “Are the students learning them? How well are they learning them? Where do they need extra help? That’s what gets lost in the testing argument. You have to have a way to measure progress. People want to know how their schools are performing. You have to have data to do it.”

Yet this is the whole point of the opt-out movement: If the system doesn’t work for you, break the system. “The entire machine runs on test-score data,” says Au. “It’s the fuel. When you take away the data, you break the machine.”

The next step, he says, is to build an alternative to that machine—to debunk the idea that this kind of testing is the only form of measurement, and this kind of data the only data that counts. “If we want our kids to be college-ready,” Au says, “then let’s make them college-ready. Let’s talk about the kinds of learning that we associate with high levels of learning in college.”

He’d rather see a portfolio as a graduation requirement, for instance, as is already happening with a lot of success through the New York Performance Standards Consortium, a network of 28 public schools in New York state that eschew standardized tests for more comprehensive forms of assessment. High-schoolers graduate with something that looks a lot more like a dissertation defense, and over 90 percent of them go on to college. “It’s way more rigorous and way more serious,” says Au, “and much closer to what students have to know how to do in the real world.”

Meanwhile, in Seattle, standardized tests still hold court. The teachers’ strike last fall helped build in mechanisms that allow teachers to have more say in district assessments, but not so for the SBAC. The opt-out student numbers might be lower this year than last, activists say, because it is now, officially, a graduation requirement; last year, the mass 11th-grade opt-out was a statement that students could afford to make, says Edelstein. It wasn’t a requirement for the class of 2016, so he and most of the staff at Nathan Hale believed it served no purpose whatsoever.

Now, though, the tables have turned. “How can kids afford to opt out of a test they need to graduate? That is more than we could expect of them.” Families are the ones that need to speak up, he says, and the professors in schools of education, and professional leaders in assessment, “to make a statement that American education is not best assessed through high-stakes standardized tests.”

Susana Lopez, for one, is opting Melanie out again this year, and anticipates that she’ll also opt her other daughter out of the SBAC when she’s in third grade. She says she doesn’t advocate for opting out per se. She just wants parents to be informed: These tests may not be all they’re cracked up to be.

“If you live in a neighborhood that is well-off, you have a better chance of doing well on every single test they ever give you,” she says—no matter how many tests, no matter how much time teachers spend teaching to the tests.

And then, echoing nearly every teacher who has spoken out about this issue since the dawn of the debate: “What if we stopped testing so much and used the extra time for things like teaching?”