Preston Singletary, a local visual artist who ascended to fame by combining glass art with his Tlingit cultural heritage, had quite a special 50th birthday party. He’d just contributed to a Kickstarter campaign for a new tour van for one of his longtime musical idols—Parliament/Funkadelic and Talking Heads keyboardist Bernie Worrell. As a Kickstarter reward, Worrell promised he would drive the van out and play a private show. Singletary turned it into his party.

To honor Worrell’s trip, Singletary, also a musician, sang Worrell a traditional Native welcoming song before the band started. “So what happened was,” Singletary tells me from his art studio, “he took this melody I sang and played it on the keyboard all of the sudden, changed it, and expanded it… and then seamlessly segued it into his own music. I was … totally blown away.” Singletary would have the chance to formally open for Worrell’s band the next day at a public gig, playing bass in his own “native funk” band, Little Big Band. Before Worrell left—intrigued by Singletary’s desire to fuse indigenous culture with funk, a style of music he helped create and develop throughout his legendary career—he suggested the two get together and play sometime. “I had to pinch myself,” Singletary says.

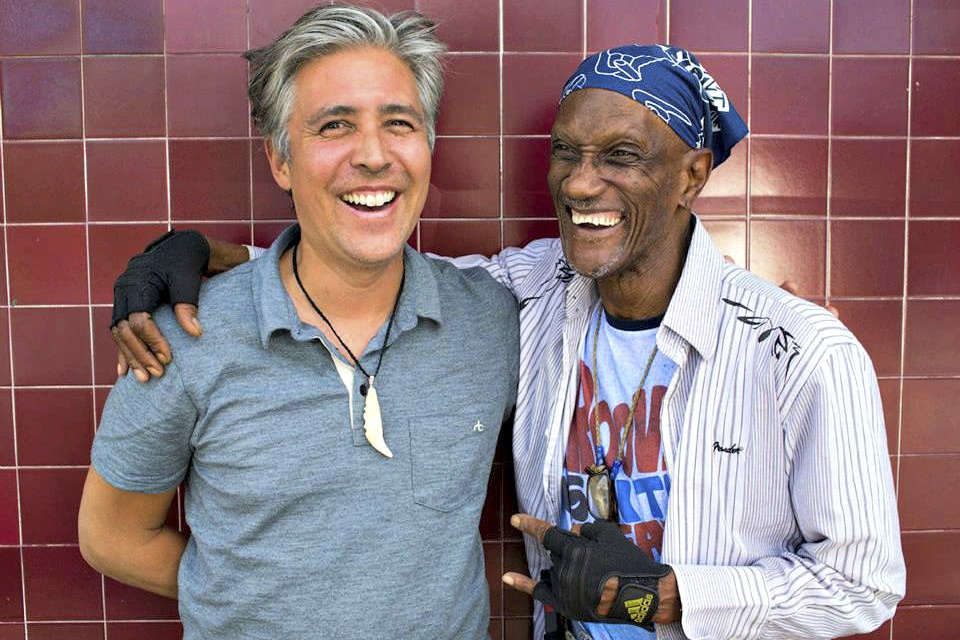

The result, Khu.éex’ (pronounced koo-eex, the Tlingit word for potlatch), is a fascinating, genre-busting musical project featuring some of the city’s finest Tlingit artists and storytellers, such as Nahaan, Clarissa Rizal, and Gene Tagaban, working with funk and jazz greats like Worrell, local saxophonist Skerik, New Orleans funk drummer Stanton Moore, and New Mexico guitarist Captain Raab, as well as noted Seattle producer Randall Dunn. The recordings would be Worrell’s last before cancer took his life in June at age 72.

The Wilderness Within, the first of many promised albums to come out of the loads of mostly improvised material the band recorded over five months, truly earns its “experimental” label. Songs like “Angry Bear” layer more familiar groove-based funk sounds under traditional spoken-word Tlingit stories. “To Her Grandmother” goes even further out, placing Rizal’s tale about weaving, her ancestors, and the march of colonial capitalism atop a swirling, psychedelic blanket of ghostly sounds. Live, the band connects the dots by performing in Northwest Coast masks and playing traditional bentwood box drums.

This week, the band will play one of its first shows since Worrell’s passing (locals Tim Kennedy and Davee C will take Worrell and Moore’s place), but Worrell is still firmly in Singletary’s memory. “Bernie is Cherokee,” Singletary says. “He didn’t know too much about his Native roots; it wasn’t something he nurtured, which I understand. He was busy touring the world, you know? But I think this project brought him something; he really responded to everything we had to say about the culture and the context of the stories and the music, and was so enthusiastic to work with my native friends.” Two months before his passing, Khu.éex’ played one final show with Worrell on April 19 at the Nectar. “That day happened to be his birthday,” Singletary says. Khu.éex’, Town Hall, 1119 Eighth Ave., khueex.com. $10–$20. All ages. 7:30 p.m. Sat., Oct. 29.